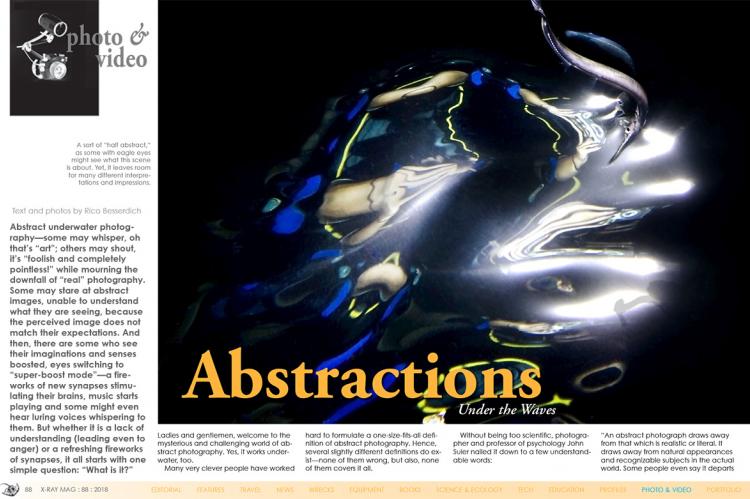

Abstractions

Abstract underwater photography—some may whisper, oh that’s “art”; others may shout, it’s “foolish and completely pointless!” while mourning the downfall of “real” photography. Some may stare at abstract images, unable to understand what they are seeing, because the perceived image does not match their expectations.

And then, there are some who see their imaginations and senses boosted, eyes switching to “super-boost mode”—a fireworks of new synapses stimulating their brains, music starts playing and some might even hear luring voices whispering to them. But whether it is a lack of understanding (leading even to anger) or a refreshing fireworks of synapses, it all starts with one simple question: “What is it?”

To isolate specific parts of an object always works well in abstract photography, underwater and above. Photo by Rico Besserdich.

Tags & Taxonomy

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the mysterious and challenging world of abstract photography. Yes, it works underwater, too.

Many very clever people have worked hard to formulate a one-size-fits-all definition of abstract photography. Hence, several slightly different definitions do exist—none of them wrong, but also, none of them covers it all.

Without being too scientific, photographer and professor of psychology John Suler nailed it down to a few understandable words:

- “An abstract photograph draws away from that which is realistic or literal. It draws away from natural appearances and recognizable subjects in the actual world. Some people even say it departs from true meaning, existence, and reality itself. It stands apart from the concrete whole with its purpose instead depending on conceptual meaning and intrinsic form . . . Here’s the acid test: If you look at a photo and there’s a voice inside you that says 'What is it?' Well, there you go. It’s an abstract photograph.” [Source: Photographic Psychology: Image and Psyche, Prof. John Suler, True Center Publishing, 2013]

It is in the nature of photography itself that many photographers—underwater and above—love to stick to “rules.” Some of those are defined by technical aspects such as camera and strobe settings and optics. Others are defined by dogmas, which have turned into “laws“ just because enough people have repeatedly used them endlessly over the decades. There is nothing wrong with that, but let's entertain the thought that photography works on many different levels and dimensions, many of them yet to be discovered. There is never a 100 percent clear “right” or “wrong.”

This, however, is no invitation to mess up your shots and claim them to be “abstract art” later on, waiting for MoMA (Museum of Modern Art, in New York City) to pay you a fortune for it. In a way, abstract photography (whether one likes it or not) requires mastership and a profound knowledge of photography.

But most of all, it requires something money can't buy: the ability of the photographer to dive down deep into the essence of a subject in order to photograph and turn it all into something new. Something that (if we are lucky) turns on the music and alters the “what is it” question into a steady stream of new impressions and thoughts. Available technology such as cameras, lenses and image-editing software do, of course, come in handy, but they are still unable to compete with the eyes and mind of a creative and thoughtful photographer. This means: Don't mind your photo gear too much. It’s just fine and will do the job.

To help us understand abstract photography a bit better, let's see Wikipedia's definition of it, and let's add a few “translations.”

- “Abstract photography, sometimes called non-objective, experimental, conceptual or concrete photography, is a means of depicting a visual image that does not have an immediate association with the object world and that has been created through the use of photographic equipment, processes or materials.” (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abstract_photography)

The bad news: Your collection of “eyes of fish” cannot be called abstract photography, as it is clear to viewers that those images display eyes of fish. It means that an immediate association with the subject exists, which can be interpreted as contrary to the definition of abstract photography.

But at least we are still allowed to use our cameras, and digital post-production is a nice tool in the creation og abstract photography. In analog photography, and later in printing, much could be done by changing or altering the materials (such as paper type).

Wikipedia goes on to state:

- “An abstract photograph may isolate a fragment of a natural scene in order to remove its inherent context from the viewer, it may be purposely staged to create a seemingly unreal appearance from real objects, or it may involve the use of color, light, shadow, texture, shape and/or form to convey a feeling, sensation or impression.”

The good news: We can isolate fragments of our photo subjects underwater, not to answer the question “what is it?” but to let our viewers come to their own impressions, develop feelings, or hear luring whispers or music. Isolation of specific fragments of a subject works well in abstract underwater photography, and in any case of doubt, “unreal” images make viewers take a closer look at our images. We do not want people to spend just two seconds looking at our images, hit the “Like” button, and then leave. We, of course, want them to look longer, think a bit deeper, reflect... and turn the music on.

Lastly, Wikipedia states:

- “The image may be produced using traditional photographic equipment like a camera, darkroom or computer, or it may be created without using a camera by directly manipulating film, paper or other photographic media, including digital presentations.”

Sounds almost like unlimited freedom, doesn’t it? At least, as long as you are not about to enter underwater photography contests. While I prefer to create abstract images with a camera only, or in camera (call me a purist!) and post-production—in this case, it is better to say that ”digital image manipulation” is considered a “legal” tool in creating abstract images.

Analog photographers can have lots of fun in the darkroom experimenting with acids, proteins or even urine (oh yes, that’s been done already!) on their films and papers. Those who now trust in digital image sensors might prefer image-editing software, as it is well known that digital camera sensors do not act well with proteins… or “worse things.”

Let's summarize

Abstract photography:

- • Is non-objective, with no immediate association with the subject. The subject is secondary.

• Makes beholders think and reflect (“what is it?”), allowing them to develop their own impressions and feelings.

• Understands the real essence of a subject, digging deep, thinking deep.

• Plays with patterns, textures, color variations, tonal variations, curves, shapes and geometry, blurring, angles and focus to create special abstract images.

• Is brave, playful and experimental. Let the music play!

By the way, abstract photography is not new at all. The first abstract photograph was created in the year 1842 by John William Draper. His works did not make it into the Museum of Modern Art but into the Smithsonian—that’s also quite something.

Looking at all the factors that can make a photograph an abstract one, we can now agree that there is a lot of potential for shooting abstract underwater images.

A photo dive with the aim of bringing some interesting abstract shots back home requires a different way of seeing things during that dive. It also requires one to forget (for the moment) some “rules“ of classical underwater photography.

I need to add that when it comes to abstract photography, there simply is no “middle” ground: Some people love it and some people hate it. It is a question of personal taste and preferences, but the attempt to open our eyes and senses to abstract imagery sharpens the photographic eye and stimulates our creativity. Suddenly, very common or even “boring“ subjects offer new photographic potential. We only need two things: the eyes to see it, and the will to express something different.

Time for a warm-up!

The good news first: Almost any camera can do it. Compact cameras, DSLRs, mirrorless cameras—they all are generally suitable for abstract photography. The same is true for lenses. Prime lenses (with fixed focal length), zoom lenses, wide-angle, fisheye or macro lenses—they all work.

In abstract photography, there is no need to be too scientific or even picky about technology. But it still helps to know how to use the technology available to you. The journey to abstract photography is a journey into your inner self, your imagination, creativity, and most of all, your ability to think deeper, uncovering the heart and soul—the very essence—of the subject in your photograph.

So, instead of talking about camera models, settings, lenses and stuff, let's activate some new synapses. Before we shoot, we think. Let's try a mentally abstract approach to a popular underwater photography subject—the shark.

Now, when thinking about sharks, what comes to mind? Perhaps elegance, beauty, speed, evolution, grey color, big teeth, rough skin? Anything else? Just take your time and think about what makes a shark, a shark. Write down a few short words or characteristics. There is no need for a complete list. What is important is your very own thoughts and impressions.

However, please exclude thoughts like:

- • expensive

• needs a wide-angle lens

• no holidays left

• scuba regulator needs to get serviced first

• needs a better camera

These thoughts are not helpful at all during this little creative brainstorming.

Pick one of the characteristics you have listed. Incidentally, I have picked “speed.” Now comes the question: How does one express speed (of a shark) in an abstract photograph? I have to confess, my pick was actually not that incidental.

Most likely, your spiritual and creative mind has now connected itself with your “analytical” and technical mind. Is your mind whispering phrases like “slow shutter speed,” “slow sync flash,” or “pan”? That's all right, you have incidentally just solved the task of finding a suitable photography technique. Easy thing, that was—leaving us more time for shooting.

Now, what is left to do is to go diving, find a shark and shoot images. Not everything can be planned or even staged in abstract photography. Sometimes (oftentimes, actually) things just happen, and sometimes, there is no shark to be found. But that does not matter so much. What matters is how you are now observing the world around you with different eyes.

Even in waters where there is not much to see and nothing swims, floats or crawls around, you still have the element of the water itself. Seen with the eyes of an abstract photographer, water is very photogenic and the possibilities are endless.

Seen from a more psychological perspective, abstract photography often works with something I now like to call “provocation.” And this is why: Whenever a human looks at an image, the brain automatically compares the perceived with formerly stored perceptions and knowledge.

If there is a match in the database (the brain), everything is fine. But if there is no match, the brain feels “provoked” (and hopefully stimulated), the finger moves away from the “Like” button, and brain cells on holiday are called back to attend an immediate emergency think tank. The human begins to think and reflect about the perceived. “What is it?” is just the first step. Now, try not to think about a pink shark.

Abstract photography is in a class of its own, and is certainly not meant to replace any other general themes or categories of photography. But don't go shooting nudibranchs for a magazine article and deliver images in which no one can spot a nudibranch. That wouldn't do you any good.

However, if you feel like you now have more than enough nudibranch pictures in your archive, but your preferred dive spots have nothing else to offer (except nudis), you perhaps might like to give abstract photography a try. It works perfectly with common subjects, and after all, it is always a good idea to be brave and try something new.

What works well in abstract underwater photography?

Patterns

Any kind of decorative motifs such as color patterns of fishes, corals, sun-ray reflections on the sandy seabed or even different blue tones in open water.

Textures

Anything that gives one the feeling that one is “touching it.” This could be the rough metal on wrecks, stones and rocks, skin details on a shark, the surface of a jellyfish or fish scales.

Color Variations

Anything that comes with at least two colors could work. The “abstraction” here comes from the interplay of colors. All blue and red hues work fabulously. Green and yellow hues can work as well, as long as they are bright and not dark.

Tonal Variations

Variations of color tones (different tones of one and the same color) and also black and white elements have great “abstract potential.” Tones of blue (or green) water, or the interplay of light and shadow on wrecks, are both good subjects with which to start.

Curves, Shape and Geometry

In simple words, it's about how things, or subjects, are formed or shaped. Subjects can include corals, fish fins, special underwater landscapes, wrecks (in total or only parts of them) and silhuettes of all kinds… as long as they are interesting-looking. Beware: If one can easily identify the subject, it ain't an abstract photograph.

Blur

Unsharpness—but created with intention! Motion blur, bokeh effect, panning, spinning or zooming—there are lots of ways to create an abstract shot based on, or working with, blur. This works with almost anything you can find underwater!

Angles

Unique, or even uncommon, angles or points of view can result in interesting abstract photographs. One hundred percent permission to break “classical” rules granted! From below, from behind or even diagonally... any way you like it.

Focus and Depth of Field

To set the focus at unusual points on a subject can create interesting abstract shots. Decrease the depth of field intentionally and suddenly see the very same subject in a more “abstract way.”

Is abstract photography considered contemporary art, fine art or not art at all? It doesn't really matter. What matters is opening our eyes to new visions and ideas of photography, and always staying open to something new. What is important is (as always) that you enjoy taking images underwater and that you like your photographs—even the abstract ones.

One last tip: A “serious” abstract photographer never reveals what the original subject of the abstract image is. Help your viewers use their brains, allow them the freedom of impression and keep your own freedom of expression.

Now, let the music play and never forget: “There is no must in art because art is free.” — Wassily Kandinsky ■

Rico Besserdich is a widely published German photographer, journalist and artist based in Turkey. For more information, visit: Maviphoto.com. See his latest book at: Songofsilence.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎