Clearing Mines in the Sava River of Bosnia

Landmines. They are some of the most insidious weapons mankind has ever created. Invisible, hard to destroy and waiting years for their opportunity to kill. Tens of millions are scattered around the world. In fact, Czech police divers and bomb disposal experts returned from another mission in Bosnia, where they were looking for war ammunition, especially landmines, in the rivers.

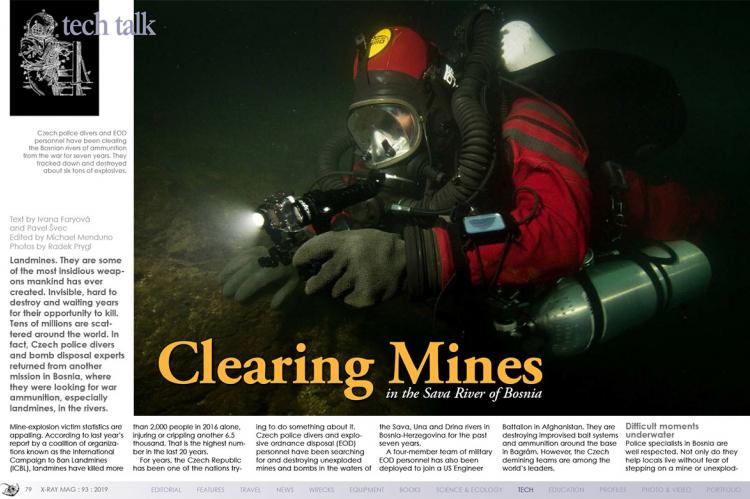

Working in rivers is made more complicated by bad visibility and current, Bosnia-Herzegovina. Photo by Radek Prygl.

Mine-explosion victim statistics are appalling. According to last year’s report by a coalition of organizations known as the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), landmines have killed more than 2,000 people in 2016 alone, injuring or crippling another 6.5 thousand. That is the highest number in the last 20 years.

For years, the Czech Republic has been one of the nations trying to do something about it. Czech police divers and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) personnel have been searching for and destroying unexploded mines and bombs in the waters of the Sava, Una and Drina rivers in Bosnia-Herzegovina for the past seven years.

A four-member team of military EOD personnel has also been deployed to join a US Engineer Battalion in Afghanistan. They are destroying improvised bait systems and ammunition around the base in Bagrám. However, the Czech demining teams are among the world’s leaders.

Difficult moments underwater

Police specialists in Bosnia are well respected. Not only do they help locals live without fear of stepping on a mine or unexploded ammunition, they also give assurance that the world has not forgotten them.

“With our help, they don’t feel like an abandoned country among the wealthy states around them,” said police diver Martin Kučera who just returned from Bosnia. “In Bosnia, we’ve seen the citizens who fled the war return for weekend visits. They come in their Mercedes, enjoy parties with fireworks, and don’t understand what happened here and what is happening now. Then they leave again. It’s hard on the locals; their memories of war remain. The people who escaped are perhaps better off than those who stayed and defended their land.”

Kučera and his colleagues have been in Bosnia since 2011, exploring the shores and bottoms of rivers in search of dangerous ammunition. The Czechs were the only ones in the world to sign up for the underwater work, where the line between life and death is pretty thin. The work is unimaginable.

You can hardly see in the mud and you are constantly drawn by the current. The danger is hidden in the sediments—one careless move is all it takes. “When you enter the water, you cannot get rid of the feeling that there are mines everywhere, which could blow up any second,” said Kučera. “It is only when you get used to the area underwater and use your detector that you can calm down and realize there is less danger, and you can kneel and have time to move in a certain direction,” he added.

Over the past seven years, the Czechs have combed through every centimeter of hundreds of meters of river flows, neutralizing tons of mines, bombs and grenades. Nevertheless, misfortunes still occur in Bosnia. For example, a recent mine explosion killed a large herd of sheep and injured the herdsmen.

Mines and ammunition were thrown into the rivers by fighters during the war. Some sank to the bottom with sunken ships, others drifted under bridges that were bombed, and some remaining munitions found their way to the riverbed through flooding.

An EOD team’s nightmare

The worst situations from an EOD team’s perspective are amateur grenades and mines, which were made by the fighters themselves, because no one knows exactly how they were assembled. The anti-personnel mines of Yugoslav origin are also a nightmare—the warring parties buried huge amounts of them in the Balkans.

One particular type of mine provokes terror: the Protupješačka Rasprskavajuća Odskočna Mina (or PROM). When stepped on, the mine is ejected above the terrain from its hiding place, before exploding and bursting with small metal balls. It is a death sentence for anything within 50 meters.

PROM still kills and maims people and animals in many countries, including Angola, Chile, Croatia, Kosovo, Eritrea, Iraq and Namibia. And soldiers set such mines around Bosnian rivers.

“When the floods come, they are washed out of the banks. Some either spontaneously explode or they get into the river, and that’s the trouble,” Kučera cautioned.

There is not an estimate as to how much work remains for EOD experts in Bosnia. “The deployment of EOD personnel in Bosnia and Herzegovina is continuing. In addition, police divers have begun to train a demining unit of the Republic of Serbia,” said police spokeswoman Eva Kropáčová, adding that sending Czech divers to Ukraine is currently being considered.

Since 2011, over 40 Czech experts have helped remove mines in Bosnia. The mission has a budget of about CZK 1.5 million per year. It is funded by the Czech Treasury through the Ministry of the Interior.

Professionals are a must

It should be mentioned that police specialists in the former Yugoslavia have already followed up on the work of their colleagues in the army. Czech soldiers have recently helped to demine the territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo. In addition, they helped Jordan and parts of Afghanistan through the ISAF operation.

“Since August, a two-man EOD service team has been deployed in NATO’s operations in Lithuania. The main task of the unit is training activities,” said Magdalena Dvořáková, spokesperson of the General Staff.

Unfortunately, despite of all the efforts of deminers around the world, the deployment of mines in recent years has been increasing in places such as Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, Libya and Ukraine. In addition, mine areas that have been overrun with new handmade mines by Islamists are incomparably more laborious because they include a significantly larger amount of explosives.

For example, the new generation of landmines that the Islamic State militants have deployed around the Iraqi city of Fallujah some time ago contains up to 15kg of explosives. By comparison, traditional mines have only about 200 grams! So, while training the local population to help with the destruction of traditional mines had been sufficient, it is not enough for the mines of this strength. Professionals are needed to take care of them, which unfortunately comes with a large price tag.

“This kind of improvised explosive device requires a much more sophisticated level of knowledge—someone who has years of experience in explosives disposal,” Stan Brown of the US Mine Removal Office told The Guardian recently.

According to the ICBL, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997, the total cost of removing mines in 2016 alone was US$560 million, or almost 13 billion Czech crowns.

Two thousand minefields

Landmines started being used in large quantities during World War II and were used in a majority of later conflicts, including Angola, Cambodia, and, of course, in former Yugoslavia. Bosnia-Herzegovina is now one of the countries with the largest number of landmines in the world.

There are about 2,000 minefields in this Mediterranean state—which is roughly two-thirds the size of the Czech Republic. What is even worse is that many more minefields are not documented or labelled. One mistake could mean the loss of life. Therefore, EOD personnel must always be on the alert. Anyone who ventures beyond the ominous “Beware of Mines” signs is at huge risk. Every year, many people in the country lose their lives or are injured.

“I believe that people in Bosnia need help. When you see their eyes light up when we are successful, when they invite you into their homes, when they come to you in the evening to thank you, and when you see how grateful they are, we realize the huge responsibility we carry,” Kučera explained. ■

SOURCE: idnes.cz

Download the full article ⬇︎