Cognition in Sharks

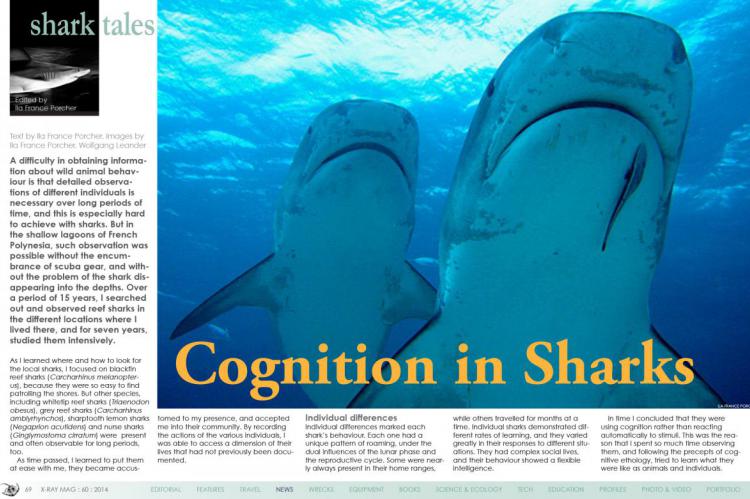

A difficulty in obtaining information about wild animal behaviour is that detailed observations of different individuals is necessary over long periods of time, and this is especially hard to achieve with sharks. But in the shallow lagoons of French Polynesia, such observation was possible without the encumbrance of scuba gear, and without the problem of the shark disappearing into the depths.

As I learned where and how to look for the local sharks, I focused on blackfin reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus), because they were so easy to find patrolling the shores. But other species, including whitetip reef sharks (Triaenodon obesus), grey reef sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos), sharptooth lemon sharks (Negaprion acutidens) and nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum) were present and often observable for long periods, too.

As time passed, I learned to put them at ease with me, they became accustomed to my presence, and accepted me into their community. By recording the actions of the various individuals, I was able to access a dimension of their lives that had not previously been documented.

Individual differences

Individual differences marked each shark’s behaviour. Each one had a unique pattern of roaming, under the dual influences of the lunar phase and the reproductive cycle. Some were nearly always present in their home ranges, while others travelled for months at a time. Individual sharks demonstrated different rates of learning, and they varied greatly in their responses to different situations. They had complex social lives, and their behaviour showed a flexible intelligence.

In time I concluded that they were using cognition rather than reacting automatically to stimuli. This was the reason that I spent so much time observing them, and following the precepts of cognitive ethology, tried to learn what they were like as animals and individuals.

Cognition is the term used for thinking in non-human animals—the process of knowing through thinking. An animal shows that it is using cognition, rather than trial and error, when it must have referred to a mental representation in order to act as it did. Many life forms, including invertebrates, are increasingly found to be using cognition in their daily lives, and cognition in fish has been well studied.

Knowing others as individuals

The sharks recognized each other as individuals, which is the prerequisite for the complex social lives in which cognition is most evident. They tended to travel with preferred companions, and these sets of friends joined with wider groups of sharks at times. Due to the circular paths in which they move, they repeatedly crossed each others’ scent trails, and thus remained in loose contact as they roamed, together, yet not usually within visual range.

Companions were individuals of the same gender, and usually the same age as well. Some sharks usually travelled alone, some always with the same companion, and others changed companions relatively frequently. Often, travellers were temporarily joined by sharks residing in the regions through which they moved. There was always excitement when travellers and residents met. They would follow each other around and swim side by side for long periods, before the companions moved on together.

As far as I was able to determine, such friends came from the same region. The reef sharks were acquainted with the other individuals whose home ranges overlapped theirs; travelling companions were usually neighbours at home.

Bonnethead sharks, too, have been shown to recognize each other as individuals, and it has been documented that at least some species of sharks and rays choose their mates, providing further evidence that individuals know each other.

Memory and learning

Learning plays an important role in the lives of sharks, as has been well documented.

Learning is closely involved with memory, and the sharks I had under observation frequently showed their ability to remember events far back in time. Familiar sharks recognized me in the lagoon as much as two years after their last meeting with me, and their behaviour, of greeting and swimming with me, was unchanged.

Like people, different sharks had different rates of learning. For example, among those who accompanied me most often, one of them never learned to take a treat I threw for her, while only a few caught on immediately without practice.

Vigilance

Wild animals are always vigilant, always on the look-out for danger, and sharks are no different. Whenever anything was different about my visit, whether it was in a different place or at a different time, the sharks’ behaviour became more cautious.

When I brought a second person with me, which happened very rarely, they initially vanished beyond visual range after a swift approach when I first appeared underwater.

Many minutes passed before they reappeared, usually approaching the stranger first, in long lines led by the boldest among them. This initial disappearance never happened when I was alone, and demonstrated their alertness to changes, and their ability to make quick decisions based on unexpected findings.

Those who complain that shark feeding dives cause sharks to harass spear fishermen, have failed to understand this crucial point—sharks easily discern the difference between a shark feeding event and a spear fisherman. It is the fishermen themselves who attract sharks, by holding dying fish underwater and trailing scent.

Approaches

All of the species of reef sharks I observed habitually used the veiling light to conceal themselves. Once out of sight, they often continued to pay attention to events from beyond visual range, by listening and through their lateral line sense. Sometimes they passed into view for a brief look just at the visual limit, then vanished again beyond their curtain of blue.

The diagram (above) shows the general pattern of approach of a blackfin reef shark.

Initially, the shark curves briefly into visual range, then out. A few minutes later, it appears again for a closer look. With each repetition, the arc becomes more acute until, if the shark is very interested, it approaches nearly head on.

Any variation on this pattern could occur. Shy older females often lingered out of visual range before making one or two passes into view, but never came close, while males coming into the lagoon in exited bands to mate after sunset, often omitted the ‘cautious passes’ phase, and zoomed straight up to me.

Other species showed a similar general pattern of approaching, but their closest approach came more from the side than head-on.

(...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #60

Indonesia's Gorontalo; Cayman Brac; Antarctica; Brazil's Fernando de Noronha; New Dalarö wreck park in the works in Sweden; Reviewing Poseidon's SE7EN rebreather; The art of bailing out; Idiot buddies; Safety culture; Scuba Confidential; Sensational snoots; Overview of photo editing software; Seacam Academy; Florida's artificial reefs; Erika Pochybova-Johnson portfolio; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, shark tales, whale tales and much more...