Giant Australian Cuttlefish

The giant Australian cuttlefish (Sepia apama) is the largest cuttlefish in the world, reaching up to half a metre in total length and weighing in at around 11kg. Solitary animals, they are found all along the coastline of the southern half of Australia—from Central Queensland on the eastern coast, right around the bottom of the continent and up to Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia.

Tags & Taxonomy

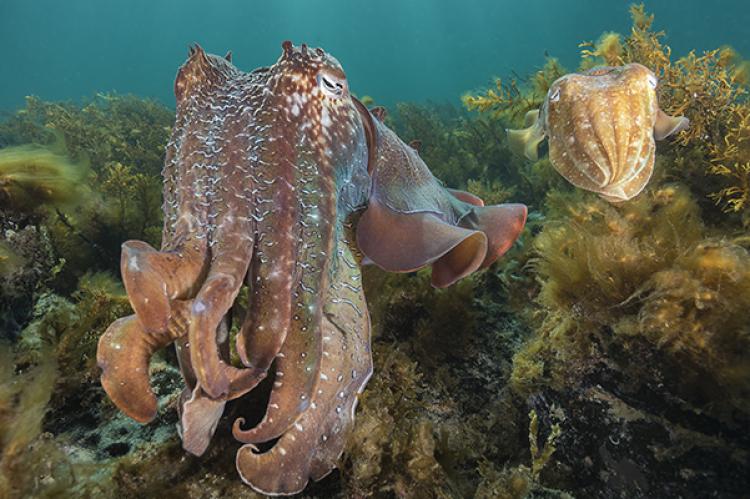

Incredibly photogenic creatures, they have a fascinating ability to rapidly change their colour and skin texture, an ability which they use to great effect as camouflage when they are hunting or being hunted, to communicate with other cuttlefish and as part of the amazing displays they use to impress potential partners during the mating season. The giant Australian cuttlefish are also remarkably intelligent and are said to have the largest brains of all marine invertebrates.

Both male and female cuttlefish have relatively short life cycles of one to two years. Interestingly, they have two alternate development cycles, with the first using a “growth spurt” over their initial seven to eight months to reach maturity by their first summer, so they are ready to mate at the start of winter. The second cycle involves much slower growth, in which they do not reach maturity until they are in their second and final year.

Although not scientifically proven, the most probable reason for the alternate cycles is that it is nature’s way of hedging bets, so that if a catastrophic event occurs one year, there is a back-up population that can still breed the following year.

Mating

As winter approaches, the cuttlefish abandon their solitary lifestyles and aggregate together to mate in small groups of up to 10 individuals—everywhere that is, except at Whyalla in South Australia’s Spencer Gulf, where hundreds of thousands gather during the annual giant Australian cuttlefish aggregation.

The reality is that you would have to be quite lucky to stumble upon a typical mating aggregation, but at Whyalla’s aggregation, you literally could walk into the sea off the beach and the cephalopod version of Sodom and Gomorrah is all around you! It has been called the “the premier marine attraction on the planet” by distinguished marine biologist Roger Hanlon of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and starts from around the middle of May each year and lasts for about two months.

Whyalla’s giant Australian cuttlefish aggregation is really quite unique as Sepia apama is not known to gather in such large numbers anywhere else in the world. It is also an incredible spectacle to behold and one that allows the underwater photographer very close access (particularly to the large bull males, something that is simply not possible at any other time). So preoccupied are the bulls with ensuring their role in the reproductive process, they simply ignore divers and photographers as they concentrate on the task at hand.

To put their dilemma into perspective—overall, the population of giant Australian cuttlefish has a male-to-female ratio of almost 1:1. But during this unique mating event at Whyalla, that ratio changes and can reach as high as eight males to one female. So, the competition is incredibly intense and explains the large bull males’ preoccupation with their captive females—one slip in concentration will ensure that the prize is seized by one of the many competitors. The stakes are very high for all the older participants, as it is the last roll of the dice for them, and all will be dead by the end of the mating season, as the cycle of life evolves and continues.

Polyandry

The technical term for how giant Australian cuttlefish mate is “polyandry,” which basically means that each female cuttlefish will have multiple male partners to ensure better genetic variability of the species. All of it makes sense from a somewhat dry overall perspective, but when viewed in practice at Whyalla, where so many cuttlefish have gathered and the females are outnumbered by as many as eight to one, it takes on a completely different dynamic, and “spectacularly promiscuous” would probably better describe the apparently licentious and almost wanton behaviour.

Apart from the larger size of adult bull males, it is almost impossible to distinguish a male giant Australian cuttlefish from a female—even the cuttlefish themselves cannot tell the difference and males display a subtle zebra pattern on their sides to signal their gender.

The large bull males will put on the most spectacular colour displays to try and attract a female, but it is up to the female whether or not to accept. Studies have shown that up to 70 percent of the time, they do not. If she does accept, the bull male will then try and keep her hidden in the sea grass—out of sight from all the other males. But that is not easy with so many other males around, most of whom are smaller and still in their first year of life.

These smaller males are often referred to as “sneakers” because, lacking the physical size and strength to challenge the bulls, they adopt an alternate strategy of pretending to be a female and sneaking in with the real female while the bull is busy fending off larger males. The interpolator then tries to mate with the female—often with great success and much to the annoyance of the bull when he realizes what is happening.

Conservation

Cuttlefish conservation in Whyalla has been somewhat of a long, but ultimately (for now, at least) successful journey. Talk to the local divers who have been around for a while and they will tell you that early on, they did not think there was anything special about the annual aggregation of giant Australian cuttlefish around Black Point and Point Lowly. They assumed that similar events must be occurring elsewhere; but as word spread and marine biologists and scientists from around the world came to see for themselves, the exceptional nature of the aggregation became clear—it just does not take place anywhere else in the world.

A great story, no doubt, but if it were not for the tremendous efforts of some of those local Whyalla divers and nature’s amazing capability to restore itself when we get out of the way, the chances are that it would now be a significantly different story. It is likely that the annual aggregation has been taking place for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

The giant Australian cuttlefish is a short-lived animal with a life cycle of one to two years. It is also semelparous, which means it has a single reproductive episode and then dies. In contrast, us humans (and most animals) are iteroparous and are capable of multiple reproductive cycles over the course of our lives.

The main aggregation area around Point Lowly and Black Point is perfectly suited for the purpose for which the cuttlefish have adopted it, as it is relatively sheltered. And unlike much of the upper Spencer Gulf—which is mainly sand, sea grass flats and mud banks—there are numerous shallow rocky reefs that are perfect places for the females to hide their eggs.

So, here is a species that has evolved and thrived in a very specific manner because it has the almost perfect location to ensure its propagation; then, along comes man. Things changed significantly for the giant Australian cuttlefish population of the upper Spencer Gulf back in 1997 when about 250,000 of them—roughly 250 tons—were taken during the annual aggregation by commercial fishermen for export to Southeast Asia.

Up until 1997, there had been very limited recreational and commercial fishing of the cuttlefish, but so lucrative was the 1997 catch that the word spread. In 1998, a much larger contingent of boats arrived in Whyalla even before the cuttlefish did. Within four weeks, an estimated 150 tons of cuttlefish had been harvested, and the stock was so devastated that there was basically not much left to catch.

Surveys

After much local lobbying, the South Australian Primary Industries Minister stepped in and, in a widely-applauded decision, closed the area to fishing until September 1998 and ordered a three-year assessment of the overall situation. In 1999, SARDI (South Australian Research and Development Institute) assessed the upper Spencer Gulf population at 182,585, and their subsequent surveys in 2000 and 2001 showed similar, but slightly less numbers. The next proper survey was in 2005 and then again in 2008—which showed respective numbers of 127,785 and 75,295.

SARDI commenced their surveys again in 2013 and recorded a total population of 13,492, meaning a 97 percent decline against the 1999 high of 182,585—which, in itself, was recorded after the loss of about 400,000 cuttlefish because of the devastating harvesting in 1997 and 1998. Those terrible numbers in 2013 prompted a total ban on catching cuttlefish in the upper Spencer Gulf and most interestingly the SARDI surveys of 2014 recorded a population of 57,317 in 2014 and 130,771 in 2015—which would indicate that the total ban is working, but the total population is still well below where it was after the terrible events of 1997 and 1998.

So, for now at least, it appears that the immediate danger has passed, and we can thank the tremendous lobbying efforts of the local Whyalla diving community for that. ■

For more information and insight on these wonderful creatures, plus the logistics of diving with and photographing them, check out Don Silcock’s Complete Guide to the Giant Australian Cuttlefish. The author’s website has extensive location guides, articles and images on some of the best diving locations in the Indo-Pacific region. See: Indopacificimages.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎