Italian Hospital Ship Po

In the Bay of Vlora (Valona), Albania, resting at a depth of 35m, lies one of the largest and most impressive wrecks in the whole Adriatic, that of the Italian hospital ship Po, sunk by British torpedo bombers on 14 March 1941. In the darkness of the night, the pilots were not aware that the ship was a hospital ship. In the attack that ensued, 21 on board the ship died, including three nurses; one of whom was Mussolini’s daughter, Edda Ciano, who was working for the Red Cross.

I am on the coast of the Bay of Valona, together with Massimiliano Canossa, Michele Favaron, Edoardo Pavia, Mauro Pazzi and Igli Pustina for the third IANTD Expedition in Albanian waters. The window of our hotel room overlooks the nearby beach; and as my gaze wanders across the bay, I cannot help but imagine the historical hospital ship Po sitting out there so many years ago.

“The Countess shipwrecked right on this beach,” an Albanian friend tells me. “Italian soldiers arrived, they got her into a truck and took her away." The countess was Edda Ciano Mussolini, the daughter of the Italian dictator who was travelling on the hospital ship Po as a Red Cross nurse. The Po was one of the 22 white ships used to repatriate sick, shipwrecked and wounded during the Second World War.

The Po arrived in the Bay of Valona on the evening of 14 March 1941 and moored about a mile from the mouth of the River Secco, quite close to the coast. This was to facilitate the next day's transfer of the wounded on board to ambulances and trucks from the barracks of military hospital no. 403, which was located on the hill behind us. By order of the Command of Marina di Valona, the hospital ship was not illuminated during the night, as the lights would have made it possible for British reconnaissance planes to identify the other ships moored in the bay.

Shortly after 11 o'clock that night, five British torpedo airplanes from a base on the Greek island of Paramythia made it across the Karaburuni Peninsula mountain range on the other side of the Bay of Valona without being intercepted. As it reached the sea, a torpedo was unleashed from a Swordfish torpedo bomber under the command of Lieutenant Michael Torrens-Spence. It hit the hospital ship on the starboard side. In the matter of a few minutes, the Po began to tilt, so the order was given to abandon ship and launch the lifeboats. During the ensuing turmoil, a lifeboat capsized, drowning two Red Cross nurses while a third lost her life trying to save them. Ten minutes after the torpedo struck, the ship sank, leaving only the main mast, which for years indicated the exact point of sinking, above water.

Wien, Vienna, Po.

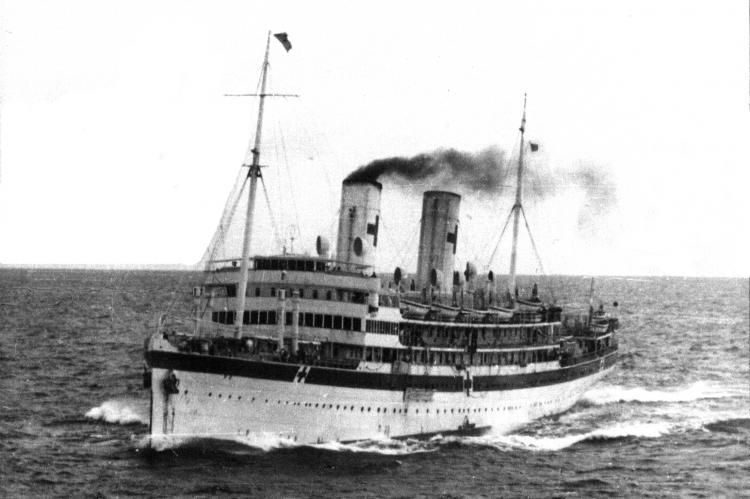

The ship was launched on 4 March 1911 by the Lloyd Austrian shipyard in Trieste, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and named Wien (Vienna) for the Austrian capital. Like her sister ship, the Helouan, the Wien was a luxurious and fast steamer of 7,289 gross tons, 135m long and 16m wide. It was used for passenger transport on the route from Trieste to Alexandria in Egypt. It had cabins for 185 first-class passengers, with another 61 in second class and 54 in third class. The engine system consisted of eight boilers and two engines which could propel the vessel at the decent speed of 17 knots.

On 16 February 1916, after the outbreak of the First World War, it was requisitioned by the Kaiserliche und Königliche Kriegsmarine (the Hapsburg [HABSBURG? AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN?] Navy), and transformed into a hospital ship. In this capacity, it was used for a few months until, on 29 June 1916, she ran aground and damaged her propellers, after which she was returned to her owners—the Austrian Lloyd—for repairs. On 7 December 1917, she was requisitioned once more and based at Pula at the tip of the Istrian Peninsula, where she was used as a barracks ship for the U-boat crews of the Kaiserliche Marine base in the Istrian port.

On the night between 31 October and 1 November 1918, the Wien, moored inside the port of Pula, became the target in an assault by the Italian Royal Navy.

Two special forces officers, Raffaele Rossetti and Raffaele Paolucci, using an underwater vehicle called mignatta (which was akin to riding a torpedo), managed to make their way past the barriers and obstructions protecting the port and used limpet mines to sink the SMS Viribus Unitis, an Austro-Hungarian dreadnought battleship of the Tegetthoff class.

After placing mines on the battleship, Rossetti was discovered and captured. He informed his captors that the ship was about to sink but was not believed as he did not reveal that he had placed mines on the hull. When the mines exploded, the Viribus Unitis capsized and sank with heavy loss of life. After placing the charges, the manned torpedo [AM NOT SURE IF IT IS OBVIOUS ENOUGH THAT THE 'MANNED TORPEDO' REFERS TO THE MIGNATTA..] was scuttled, activating its self-destruction mechanism. Before exploding, it had come to rest near the Wien, and its explosion caused the steamer to sink.

Refloated and repaired in 1919, the steamer was returned to her former owner who, since Trieste had become part of Italy following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, had changed its name to Società Anonima di Navigazione Lloyd Triestino. It was registered under the Naples Maritime Compartment, with the Italianised name of Vienna, and resumed its previous functions as a steamer in 1921, on the Trieste-Venice-Brindisi-Alexandria route to Egypt.

In 1935, with the outbreak of war in Ethiopia, it was first chartered and then requisitioned by the Italian Navy for the transport of the wounded and sick. However, it was classified not as a hospital ship but as some sort of intermediary infirmary ship. The Italian government wanted to take full advantage of every single journey from Naples to Massawa, Ethiopia, by having it carry soldiers and ammunition on the outward journey and embarking the wounded and sick on the return journey. Hospital ships, which were afforded protection and had to be painted white with green bands and red crosses, could not be used to carry healthy troops and supplies.

After the colonial war, it was returned to Lloyd Triestino, renamed Po and resumed civil service. The last years of peace passed. Following Italy’s entry into the Second World War on 21 November 1940, [IS THE DATE CORRECT?] it was again requisitioned by the Italian Royal Navy, which this time designated it as a hospital ship. It was painted according to the guidelines established by the Geneva Convention: white hull and superstructure, green belt interrupted by red crosses on the sides and the funnels. After working on the Libyan front, from Tripoli and Benghazi, to repatriate the wounded of the North African campaign, she was sent to the Lower Adriatic to provide assistance to the wounded from the Greek-Albanian front in February 1941.

The sinking

The legendary British 815th squadron flying Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers were transferred from the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious to the airfield on the Greek island of Paramythia near the Albanian border on 12 March 1941. Their orders were to carry out raids on the ports of Valona and Durazzo, and the Italian military bases of Berat and Tirana. At 9:15 p.m. on 14 March, the Swordfish were each armed with a 730kg torpedo. They passed, at 10,000ft of altitude, the mountain chain south of the Bay of Vlora and reached the sea, thereby spotting the Italian navy and merchant fleet vessels at anchor in the harbour.

Painted in white, with green bands on the sides and large crosses on the funnels, always illuminated and recognisable during the night, the Po hospital ship enjoyed the protection of the norms of humanitarian law. The international agreements—the Hague Convention 1906 and Geneva 1907—foresaw that in order to guarantee the night-time safety of hospital ships, they should be completely illuminated. A ship illuminated in the darkness could, however, also serve as a beacon for enemy aircraft. If the Po had been lit up that night, the nearby ships, which were legitimate targets, would have been made visible too. Therefore, the Marine Command gave orders to obscure it, making it indistinguishable from normal transport vessels.

On 14 March 1941, the night was clear and moonlit. Descending to the altitude of 5,000ft after passing the mountains of the Karaburuni Peninsula, Lieutenant Michael Torrens-Spence, as he would describe later in his report, managed to identify a quite visible but unilluminated target and launched a torpedo. At 11:15 p.m., the torpedo hit the Po on the starboard side. Following the explosion, a large hole opened, causing the ship to sink so quickly that the commander immediately gave the order to abandon ship. Just two minutes after the torpedo hit, sea water began to enter the stern, and four sailors were trapped in the now submerged compartment.

Of the 240 people on board, 20 crew members lost their lives, as well as four Red Cross nurses—Wanda Secchi, Emma Tramontani and Maria Federici—during the shipwreck; and a few months later, Maria Medaglia, from blood poisoning, for ingesting contaminated water. The then 30-year-old Red Cross nurse, Edda, the eldest child of Benito Mussolini, survived by reaching the beach of Radhima on a makeshift craft. The Po's keel settled at a depth of about 35m. The steamer was so imposing that the top of the mast stuck out of the water by over a metre, thereby indicating exactly the point of the shipwreck. Since then, the wreck has remained in the Bay of Valona, less than a mile from the Albanian coast.

The dive

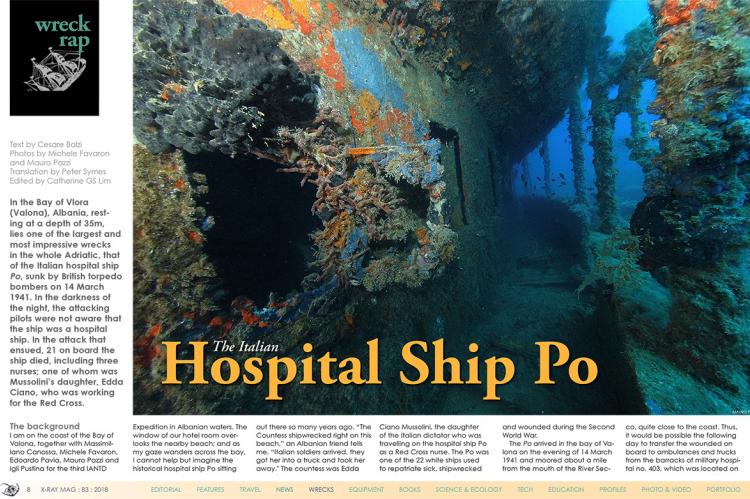

Once in contact with the wreck, we noticed that visibility was good and there was a total absence of current. In the beginning, it was easy to be overwhelmed by the desire to want to visit everything, finding yourself in the end, swimming in a frantic way, between the decks, but the experience gained in previous dives and timely planning made us proceed with utmost caution. The first image we glimpsed was an evocative one of the bow, which immediately highlighted the vertical seams of the ship.

From the ship's left-hand-side hawse pipe, the anchor chain emerged, which on that fateful night of 14 March 1941 kept the ship stationary at anchor. On the starboard side, Maximilian lingered near the anchor, which still sat in its hawse pipe, on the side of the bow. Leaving the end of the prow, our dive proceeded towards the stern. What immediately caught the eye was the excellent state of preservation of the bridge deck, whose wooden tables in marine teak were still intact, clean and perfectly aligned with each other.

After passing a group of bow winches, we reached the mast, now lying on the deck after years of rising up to more than a metre above the surface of the sea. Today, the mass of beams and cables lay horizontally on the main deck, across the openings of the two bow holds. Inside the first one, in a boatswain’s cubicle, we found large quantities of tools for mooring the ship. In the second were bathrooms, within which the ceramics that covered the walls, sinks, toilets and baths were still perfectly preserved.

After the exploration of the forward part, we arrived at the imposing superstructure, which we easily entered through the large windows and got into what was once the bridge. It was necessary, however, to pay attention to sharp metal and abrasive surfaces, and to be mindful that visibility could be reduced. In this manner, we explored the internal compartments, using a reel to lay out a guideline with positioning markers and cookies, as underwater signage showed us the safe way out. The missing decks made the interior a unique and scenic environment. From where once there were the windows, the light penetrated, creating a spectacular and evocative play of shadows and colour. It is a place where everything had come to an abrupt stop; and the diver, between those walls and those well-known rooms, could not help but reflect on the events of the war.

The ship, in addition to transporting the injured, also provided medical treatment. On board were an operating room, several clinics, and even x-ray facilities and laboratories. The wide hatches that passed through several decks were used to lower the most injured (on stretchers) to the various decks. It was still possible to go down into the rooms below and explore the lower decks of the ship, but it was important to pay attention to sedimentation and ferrous material, which, when disturbed by passing divers or their bubbles, tended to move or detach from the ceiling, jeopardising visibility.

Under the fans still hanging from the ceilings, between stacks of plates and cups perfectly interlocked into each other (not to mention glasses, bottles, vials, hospital instruments and stacked beds), one could take a leap in time and feel immersed in history. Outside the hull, proceeding towards the stern, one could see the cranes of the boats, and, just below, two floors of external corridors.

Even in the stern area, the deck was perfectly intact. Moving away a few metres in clear water, one could appreciate the elegant profile of the stern and the rudder, standing up ten metres tall. The propellers were partially covered up, but still visible, at a depth of about 30m. The gash caused by the torpedo was located in the middle of the starboard side. The opening was wide enough to enter, while the jagged edges and metal curving inward testified to the violent explosion and the subsequent, sudden inflow of water, spelling the ship's demise. ■

Download the full article ⬇︎