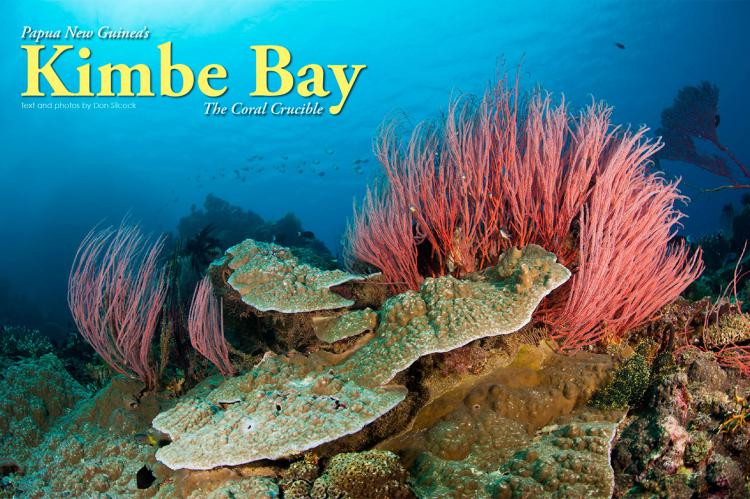

Kimbe Bay

There is a line of thought in the scientific community that this is where it all began and the first corals originated… a large sheltered bay, roughly one third along the north coast of the island now called New Britain. The bay is called Kimbe and the country is Papua New Guinea—the wild and exciting nation crafted together in colonial times from the eastern half of the huge island of New Guinea and a string of other islands stretching out in to the Bismarck and Solomon Seas.

Tags & Taxonomy

There can be no doubt regarding the profound fecundity of Kimbe Bay because the numbers, as they say, cannot lie and surveys by some of the best known names in marine biology, such as Professor Charles Veron and Dr Jerry Allen, and respected organizations like The Nature Conservancy, have helped to establish a bewildering array of statistics for the area.

Depending on which survey results are used, Kimbe Bay is host to around 860 species of reef fish, 400 species of coral and at least 10 species of whales and dolphins. To put that in a global perspective—in an area roughly the same size as California, Papua New Guinea is home to almost five percent of the world’s marine biodiversity. Just under half of that fish fauna, and virtually all of the coral species can be found in Kimbe Bay, which means that the bay can be considered as a kind of fully stocked marine biological storehouse.

Location, location, location

New Britain is part of the Bismarck Archipelago, which forms the southern ridge of the so-called Ring of Fire—the volatile and unpredictable, horseshoe shaped, seismic strip of oceanic trenches and volcanic arcs that wreak periodic havoc and destruction around the Pacific Ocean basin.

The islands of the archipelago were formed some eight to ten million years ago as a result of what geologists refer rather mildly to as volcanic uplift. The flight from Port Moresby into Hoskins Airport on the southern edge of Kimbe Bay will put the whole uplift concept into a slightly more dramatic perspective.

As you cross the narrow Vitiaz Strait from the main island of New Guinea, you will catch your first glimpse of New Britain, and you will see the western tip of a narrow crescent-shaped island roughly 500km long, by about 30km wide at its narrowest point and 150km at its widest.

Running along the spine of the island are huge mountain ranges, created by those volcanic uplifts, which are so high they effectively isolate the north coast from the south and create their own weather patterns, so that while the north coast follows the normal monsoonal seasons the south is completely opposite.

The mountains also create a partial rain shadow over the north, making the south coast the second wettest place on earth, with annual rainfalls of between six and eight meters.

The approach into Hoskins Airport takes you over the Willaumez Peninsular, the western boundary of Kimbe Bay, and provides a spectacular introduction to the other visually defining feature of this part of New Britain—volcanoes.

On the tip of the peninsular are two large freshwater lakes occupying the huge caldera left by the massive eruption of the Dakataua volcano some 1,150 years ago and then dotted along the long and narrow isthmus are three smaller volcanoes.

The final approach into Hoskins is overshadowed by the large Mount Pago volcano, and its two smaller siblings, whose periodic rumblings provide very poignant reminders of the powerful seismic phenomena far underground that created those volcanic uplifts.

Beneath Kimbe Bay

Bounded by the long Willaumez Peninsular to the west and Cape Tokoro, some 140km to the east, Kimbe Bay is sheltered from the worst of New Britain’s weather. Along the coastal area of the bay, a 200m shelf runs parallel to the shore for about 5km before dropping down to around 500m and up to 1,000m in the eastern part. On the northern outskirts of the bay as it approached the Bismarck Sea, the seafloor drops off rapidly to in excess of 2,000m.

Across this deep seascape are dramatic seamounts and coral pinnacles that rise up towards the surface and provide isolated ecosystems for the marine creatures of the bay.

The seamounts in particular act as beacons to the bay’s diverse and prolific pelagics and marine mammals—with 12 species of mammals identified to date, including sperm whales, orcas, spinner dolphins and dugong.

The deep waters and generally benign conditions function as a kind of marine nursery and are fundamental to the incredible biodiversity of Kimbe Bay, but the other significant element are the nutrient-rich currents of the Bismarck Sea that provide the nutrients to sustain the bay’s residents and visitors.

To the south of New Britain are the 4,000m deep-water basins of the Solomon Sea which the Southern Equatorial Current crosses as it makes it way towards the Bismarck Archipelago. As this powerful current approaches the south coast of New Britain, it creates upwellings that suck up the nitrogen and phosphorous laden detritus of the sea from the deep basins.

Those nutrients are carried north through the Vitiaz Strait in the west, and the St Georges Channel (between New Britain and New Ireland) in the east, in to the Bismarck Sea where they enter the predominantly anticlockwise circulation produced by the regional current flows.

As those currents flow along the north coast of New Britain and around the top of the long and narrow Willaumez Peninsula, eddies are produced in the western part of Kimbe Bay that direct the nutrient rich flows into the bay and induce further upwellings from the deep water basins to the north.

In a nutshell, the incredible forces of nature have combined to produce an almost perfect natural environment to create and sustain the coral crucible and the creatures that cohabit with it.

Diving Kimbe Bay

Kimbe Bay is one of the global locations that most divers want in their logbooks. But it is a special kind of diving, as it’s not a shark-lover’s paradise or somewhere you go because manta rays or whale sharks aggregate at certain times of the year.

My personal definition would be “fish-bowl” diving, as it is like being immersed in a fully stocked aquarium, but with a considerable random factor of nature in that you never know what is going to come in from the blue—such as that day at Susan’s Reef, when I left three other divers on the deco line at the end of my safety stop and got back in the dive boat.

Vaguely wondering what was taking them so long, I am sure you can imagine my reaction when they eventually got in the boat

(...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #62

Diving Thailand's Similan Islands at Khao Lak; Papua New Guinea's Kimbe Bay; Malapascua Island's Thresher Sharks in the Philippines; The Coral Triangle's Biodiversity; Spain's España Wreck; HTMS Sattakut Wreck at Koh Tao Island; Just Culture; Scuba Confidential; Diving Solo; Freediving for Underwater Photographers; Evie Dudas profile; Interview with artist Jason deCaires Taylor; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, shark tales, whale tales and much more...