Namibian Sinkholes

Who could imagine for a minute that Namibia is a diving destination?

Nobody. Despite its 2,000km of coastline, this is the mere truth. The marine temperatures are about 13°C on average, with an almost nil visibility resulting from stirred up waters and omnipresent sand. There is nevertheless a light of hope at the end of the tunnel. Some 30 years ago, caves and sinkholes were discovered, a peculiar reminder of the ‘cenotes’ in Mexico.

Tags & Taxonomy

In the old days of the German colony (1890-1915), the farmers of the north-east would draw water from these sinkholes, with electric pumps, for their cattle and in order to irrigate their farms. A hundred thousand years ago, San or Bushmen knew about their existence, too, for they gave names to these natural pits. Somehow, these inspired fear. The belief was that, whoever fell in would not come out alive!

Originating in Antarctica, and born roughly five million years ago, the cold Benguella current flows from south to north along the Atlantic coast, creating a coastal desert. For sure, these waters are rich in fish and marine life, due to the upwelling of the Benguella current. Twenty species are currently harvested—hake, monkfish, sole, kingklip, snoek, but also horse mackerel (Scomber japonicus), pilchards, anchovies, skipjack tuna, albacora, spadefish and pelagic sharks. Aquaculture is prolific, with a substantial production of oysters in Walvis Bay, Swakopmund and Luderitz (six million per year), abalone farms, mussels and agar agar in Luderitz, not to mention rock lobsters and deep water crabs. All in all, conditions that favour fishing, but which are resolutely a ‘no no’ for divers.

Geology

Once upon a time, the region was called Süd-West Afrika by the Germans. The actual territory of Namibia is a very old land, geologically speaking. Before the creation of Gondwanaland, some 540 million years ago, Earth was a huge ocean with some isolated ‘cratons’, which are commonly referred to as the original crust of the planet. Two thousand five hundred million years ago, southern Africa was made of two cratons: the Congo craton in the north and the Kalahari craton in the south, both separated by a southwest-northeast extension of the ocean, known as Damara Sea.

Limestone like deposits were then generated. The Kalahari craton then collided with the Congo craton, with the subsequent subduction of the former under the latter.

Three hundred million years ago, Namibia was located near the South Pole and affected by tremendous glaciations. These ended 280 million years ago, when this part of the continent broke off from Antarctica.

The calcareous reef thus created in the Damara Sea 750 million years ago, were not made of coral—since it did not exist yet—but were secreted by cyanobacteria, better known as stromatolithes. These encrusting algae are the oldest living forms on the planet (3,500 million years). Deposited over a period of 100 million years, these sediments formed layers of dolomite 5,000 metres thick. Mind blowing, right?

The intensive erosion that followed over the next 500 million years and during the humid phases of the Cretaceous and Tertiary, brought about the dissolution of the carbonates, a process known as karstification. Lime or dolomite, are eroded by an acid carbonic solution, related to rainfall.

The magic triangle

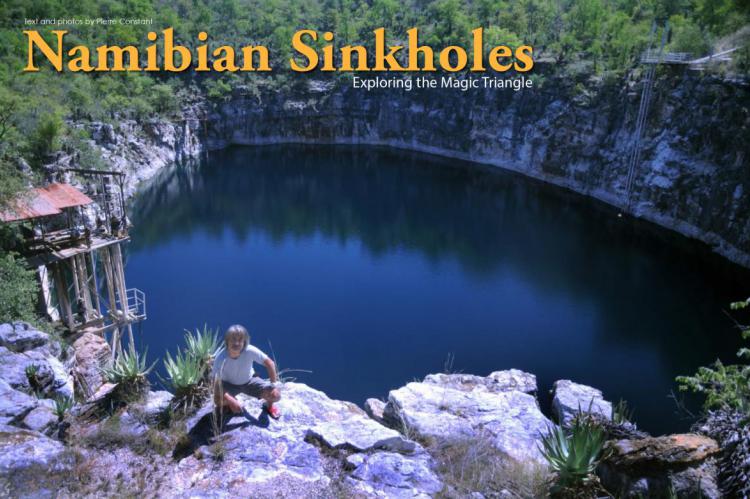

The “magic triangle” is found in the region of the Otavi Mountains, located between Tsumeb, Grootfontein and Otavi. At least 83 caves, chasms or sinkholes have been listed since 1974. A good number of those have been surveyed by Germans, South African, and Swiss speleologists since 1967 and even earlier.

Upon the occasion of one of my numerous trips to Namibia since 1992—being myself a cave diver since 2003—I decided eventually to find out about this. Accompanied by my Japanese client and friend Tetsuaki Masuda, we showed up at Aigamas farm one morning on 1 April 2013.

Cordially welcomed by Axel Bauer, a tall German farmer who could be straight out of the movie Out of Africa. We also met Chris and Steff, the fine team of technical divers from Namibia who will be responsible for logistics and security during our diving explorations.

Aigamas sinkhole

Aigamas is a local name, which in Herero language means big water. We drove up a mountain ridge of the farm with the 4x4 to get to it. The proper access did not look like much. The cave had a tent-like shape, pointed like a teepee, along a south-north fracture in dolomite limestone.

“It will be a 120 metres progression in the dark,” said Axel referring to a sketched map before we ventured inside. We all had to sign a liability release as well.

The gradual slope was negotiated partly with a metallic stairway, then we made our way with some ropes on slippery boulders covered with debris, until we reached the platform. An iron grid overlooked the pool of water about 18 metres long. From here an iron ladder plunged 5m below, down to the water level.

“The exploration and a survey attempt was done by a Swiss-Italian team in 2011-12,” said Axel.

Lead by Gerald Favre of the Swiss Société Spéléologique Genevoise, the survey map was done by Alessio Fileccia from Italy. The maximum depth of the dive was recorded at 93 metres, but the bottom was not reached. The fact is that Aigamas is a very narrow fracture that plummets into a void.

April fish

My quest today was stimulated by an encounter with the April fish (from the French saying, “Un poisson d’Avril”) and that one is no joke! Fortunately we found it, for it is endemic to the site.

Clarias cavernicola, or giant cave catfish, is a very unique species. Mostly found at the surface of the water, where it feeds on the floating guano of bats, which falls from the roof of the cave. A priori blind, the fish is about 16 to 25cm long, sulphur yellow in colour, with two pin-like turquoise blue eyes. The rounded head has the shape of a bony helmet, pointed like an arrow behind the nape.

Eight conspicuous barbels are found around the mouth, which enable the cave catfish to detect its food. It possesses a long dorsal fin, two small pectoral fins, two pelvic fins and a long anal fin that ends towards the tail, which is short and straight. Clear chevron markings are visible along the sides. The body is compressed, fusiform and eel-like. These characteristics are enhanced by the undulating movement of the catfish. Some specimens show an atrophy of the eyes, which become globulous and obviously useless.

The ancestor of Clarias cavernicola is most certainly from the Kunene or Okavango River further north, from the time when these rivers were flowing into the Etosha Pan (3 million years ago). Etosha was once a huge lake part of the Ovambo basin.

I sank down to a depth of 37 metres, in a crack that is hardly two metres wide. The water temperature was exquisite at 25°C. A number of bat corpses were found lying on the edges underwater, complete and apparently undisturbed by the catfish. It is said that the fish has also a cannibalistic behavior on the young individuals. I exited Aigamas as a true cave man, covered in bat guano, to the delight of Steff who recorded the scene on his Go-Pro, as soon as I dropped the scuba tank.

Otjikoto sinkhole

Some 20 minutes north of Tsumeb, is Otjikoto Lake—an historical site that depends on the National Heritage Council of Namibia, a government body which governs research and archeology. A diving permit is compulsory. Delivered by the Namibia Underwater Federation, it is submitted for approval by the National Heritage Council, which controls all dive activities at Otjikoto. After Chris presented our permits to the authorities and we each paid the N$25 entry fee, we were welcome to proceed.

Originating from the Otjiherero language, the name Otjikoto means, a place too deep for cattle to drink. The San called the site Gaisis, or very ugly, as it inspired fear in the bushmen.

Before the arrival of the first Europeans, the site was a trading post. Later on, the surrounding hills were guarded by armed men to prevent any exploitation of the copper ore, which was plentiful there.

Otjikoto was officially discovered in May 1851 by Charles Anderson and Francis Galton.

For the geologists, Otjikoto is a perfectly circular dolomitic sinkhole in the karst of the Damara Belt. Shaped like a calabash, the lake has a diametre of 102m and a surface of 7,075 sq m. As the depth at the centre has been estimated at 71m, the maximum depth on the sides went well beyond 145m, and to this day remains unknown...

(...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

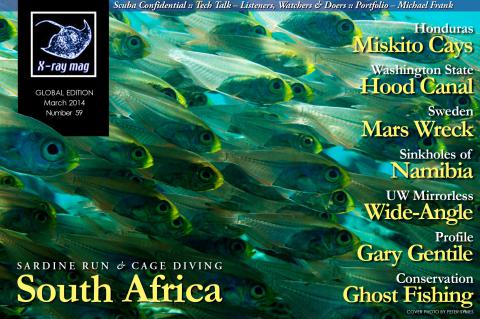

X-Ray Mag #59

South Africa's Sardine Run & Cage Diving; Honduras' Miskito Cays; Mars the Magnificent 16th century wreck in Sweden; Richard Lundgren interview; Washington State's Hood Canal; Namibian Sinkholes; Gary Gentile profile; Ghost Fishing; Basking Sharks; Wide-Angle with Mirrorless Cameras; Scuba Confidential on Breaking the Chain; Tech Talk: Listerners, Watchers and Doers; Michael Frank portfolio; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, turtle news, shark tales, whale tales and much more...