Pain in Fish & Sharks

It was Dr Lynne Sneddon, at the University of Liverpool, who proved scientifically that fish feel pain and suffer. Her team found 58 receptors located on the faces and heads of trout that responded to harmful stimuli. They resembled those found in other vertebrates, including humans. A detailed map was created of pain receptors in fishes' mouths and all over their bodies.

The experiment involved the injection of acetic acid, bee venom, or saline solution as a control, into the lips of trout, and those injected with the noxious substances responded with symptoms of pain, while the behaviour of the control group was unchanged. A morphine injection reduced these symptoms.

Tags & Taxonomy

The relief of the fishes' symptoms by the pain reliever showed the interconnection between the nociceptors, which sense the tissue damage, and the central nervous system, which recorded the damage as pain. Here was proof that fish are aware of tissue damage as pain.

“Given the evidence that the fish neurobiology, physiology and behavioural responses are comparable with pain in other animals (mammals) and painkillers reduce negative responses to tissue damage,” Sneddon wrote, “it would seem that fish do experience pain and that this is an important state for a fish to be in. Scientific data has shown fish do not show anti-predator responses when subject to pain and will avoid the area where this event happened.”

While a few countries responded by passing laws to protect fish from cruel treatment—Germany made recreational fishing illegal—elsewhere, the fishing industry worked hard to discredit the proof that the old fisherman’s tale that fish don’t feel pain is untrue.

As a result, more than a decade later, fish and sharks alone are condemned to being considered lower and simpler and less feeling than all the others. The dangerous idea that these animals can't suffer, no matter how they are brutalized, continues to stand directly in the way of their survival, perpetuated by those who kill them.

Yet, incredibly, never has evidence been presented that an animal could survive without the ability to feel pain.

The reality of shark finning

I first became aware of the prevalence of the belief that fish don't feel pain while lobbying for the protection of the sharks I was studying, who were being massacred for the shark fin racket. Their community had been dramatically disrupted when the fishing began, and they had fled the area. I searched for them in vain. Night was falling when a young shark emerged from the gloom. She was swimming with a lethargy I had seen only in dying sharks—a large hook was embedded through the angle of her mouth, with a long tear beside it. She circled once, in slow motion and glided listlessly away, became a shadow, a movement in the coral, and vanished.

She was only the first. A nightmare began in which I alternated between searching for the sharks I knew, and beseeching people to write to the government to ask that they be protected. The graceful adolescent shark eventually lost the hook, but her jaw had been damaged and she could no longer close her mouth. She lost weight over the following weeks, and within two months, she died. I wondered sadly if people who fished for fun would still do so, if they could see the unimaginable suffering that they caused.

Fishermen's arguments

But while I protested over the Internet that shark finning had hurled the sharks into a black hole of suffering, and that all sharks, all over the world, were in danger of being sucked into it, fishermen wrote to dismiss my concerns, and assure me that fish don't feel pain.

With the response of the community of sharks that were being massacred fresh in my mind, I couldn't believe what I was reading. I replied that the sharks who had escaped, as well as female sharks with extensive mating wounds, showed similar signs of pain and suffering as the mammals and birds I treated for painful injuries, as a wildlife rehabilitator. They were less alert, less responsive, and swam unusually slowly.

Pain is a warning sensation that is important for survival, and only a small percentage of fish who come into the world actually make it to adulthood—any weakness dooms them. An inability to feel pain would result in inappropriate behaviour, and the fish would go straight into evolution's garbage can. If they did not feel pain, that should be supported by observable behaviour, yet fish and sharks are shy and cautious. When you see a shark slam the side of her body against a sand bank to dislodge her remora, the question just pops out of a slot: If she couldn't feel pain, would she be so irritated by the soft touch of a remora?

Fishermen argued that they had seen sharks continuing to function in spite of terrible wounds. But this is common—even injured humans will continue to fight for their lives as long as they can when in mortal danger. The effect has an obvious benefit for survival. Others argued that fish could not feel pain because sometimes a fish will bite a baited hook a second time, after being unhooked and thrown back into the sea. But, while it may be obvious to the fisherman what he is doing, how could it be obvious to the fish?

These men assumed that the fish understood much more than it possibly could about its situation. It could have no basis among its experiences for understanding the fisherman's practice of deception. It can see no dangerous predator underwater, so how could it imagine that above the surface a man is waiting, hoping to trick and kill it? Even a human walking by the sea, would never suspect that there was a creature waiting for him beneath the surface, with a plan to trap and kill him. A fish that had already bitten a bit of food with a hook in it, has no reason to assume that the next piece of food it finds will also hide a hook. It was daunting, how many people were proud of their efforts to outwit fish. They didn't see any irony or contradiction in their claims that fish were too simple minded to feel pain, when they were so very proud that they were intelligent enough to outwit them.

A fisheries article

Further investigations revealed that in 2002, fisherman James D. Rose had published an article in a fisheries journal, asserting that fish cannot feel pain. He alleged that though they may seem to feel pain when hooked and yanked out of the water, they lack the brains to be aware of it. Fish lack the neocortex, the folded, outer layer of the brain that is so highly developed in humans, so cannot feel pain, he claimed.

According to him, the neocortex is the seat of all higher mental functions, so the required neurological machinery to feel pain is missing in fish, and indeed, is present only in humans and apes. But he did not give a reason to claim that awareness of pain depends on the neocortex, and he had done no study to back up this idea.

In focusing on a comparison of the human brain with the fish brain alone, and omitting mention of the evolution of the vertebrate brain, Rose's article seemed biased and anthropocentric. From fish to man, the brain has the same structures, arranged in the same way. The only exception is the neocortex, which developed in mammals. Neurological studies have shown that the newly evolved neocortex of mammals took over certain higher functions which were already present in fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds.

(...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

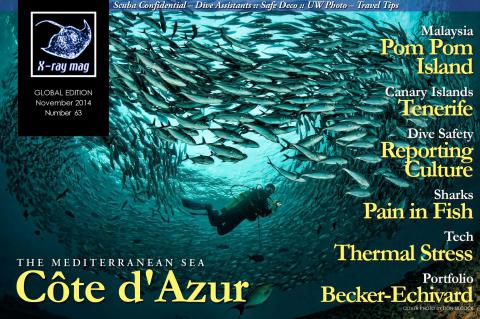

X-Ray Mag #63

Diving the French Mediterranean's Côte d'Azur, Tenerife, the Canary Islands; Do Fish Feel Pain?; Denmarks First Artificial Reef; The Physiology of Thermal Stress and How to Stay Warm; 10km on Rebreather; Reporting Culture; Scuba Confidential: Help I Need Somone; Underwater Photography: Have Camera, Will Travel; Profile and Portfolio: Becker-Echivard; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, shark tales, whale tales and much more...