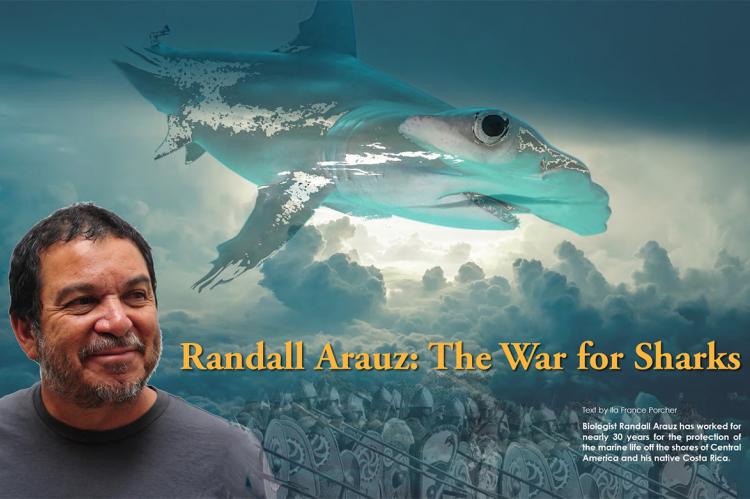

Randall Arauz: The War for Sharks

Biologist Randall Arauz has worked for nearly 30 years for the protection of the marine life off the shores of Central America and his native Costa Rica.

Randall Arauz is pressuring the Costa Rican Fisheries and Aquaculture Institute to publicly destroy fins.

Tags & Taxonomy

Arauz founded the Association for the Restoration of Sea Turtles (PRETOMA) in 1997, and it was during his efforts to protect critically endangered leatherback sea turtles that he stumbled upon the shark finning problem. He obtained some of the first known footage of shark finning on the high seas, showing how the fins are hacked off the live animal, which is then discarded at sea.

Shortly after that, his organization secured footage of of a Taiwanese vessel landing 30 tons of fins illegally at a private dock under the cover of night. The electrifying footage stirred Costa Ricans and the international community and jump-started Arauz's war to put an end to the shark fin trade in his beleaguered nation.

The shark fin racket began in the 1970s as a result of increasing demand by the rapidly growing wealthy Asian countries, called Tiger Economies. By 2001, Costa Rica ranked as the world’s third greatest exporter of shark fins.

It was during those years that the shark highways up the west coast of Central and North America, and between the oceanic islands of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, were being fished out. Costa Rica was ideally placed as a rallying point for the Taiwanese shark finning industry, which is usually described as a mafia. The country became a major shark fin landing point for international factory fishing and shark finning fleets operating throughout the Eastern Pacific. Rob Stewart's film Sharkwater, documented an incident that revealed the depth of the problem in the country, which also has a huge long-liner fleet of its own.

Arauz, who was voted one of the planet's 100 Angels in 2003 for his work for Nature, has been an Angel at war ever since, as he used every means at his disposal to try to gain protection for sharks. He alerted Costa Ricans to the slaughter ongoing in their waters, filed law suits against the government, and organized educational campaigns, petitions, and collaboration with international shark conservation organizations. His campaigns impacted domestic, regional, and global shark conservation policy. By 2014 his country was leading shark conservation policy at international conventions such as the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and the Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES).

This work earned him important acknowledgments. In 2004 he won the Whitley Fund for Nature (UK) Gold Award for his shark finning campaign. In 2010, he was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize (US) and the Gothenburg Award for Sustainable Development (SE) for his continuous efforts to halt shark finning in Costa Rica. He was awarded a PEW Fellowship in Marine Conservation in 2016 to further his studies on highly migratory species in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, and currently serves as International Marine Conservation Policy Adviser for Fins Attached Marine Research and Conservation (US).

But Costa Rica has not been consistent in its efforts to protect sharks. Though the nation has an international reputation of being environmentally conscious, the shark finning market yields profits nearly as high as that of the illegal drug trade, and the former government (2014-2018) put commercial interest first and would not protect any shark species that brought in a profit. Nor would it enforce the laws already in place to protect the marine environment. Instead, it permitted the use of a variety of loopholes that serve to enable the shark finning racket.

Hammerhead duplicity

In 2013, Arauz worked with President Laura Chinchilla (2010-2014), to lead the international campaign, along with Brazil and Honduras, to list three species of hammerhead sharks under Appendix II of CITES, a celebrated move that made Costa Rica a global leader in marine conservation, and earned President Chinchilla the Shark Guardian Award 2014, which was granted by Shark Project of Germany. As a result of these listings, governments must now prove through a scientific study that the export of hammerhead shark fins does not occur in detriment to the survival of the species. Such a study is known as a Non Detrimental Finding (NDF).

But then there was a change in government and the gains that had been made were soon overturned by the the administration of President Luis Guillermo Solís (2014-2018). By February of 2015, Costa Rica had already exported over 900 kilos of hammerhead shark fins without a NDF, and in violation of the CITES commitments the country itself had promoted just two years before. Then, it refused to support proposals to grant Appendix II listings for Silky and Thresher sharks during the last CITES meeting in 2016. Caving under pressure, Costa Rica finally banned the exportation of hammerhead shark fins as of March 1st of 2015, until there was a NDF to approve such exports.

Unfortunately, despite the export ban, the Luis Guillermo Solís administration permitted the shark fin industry to continue fishing for hammerhead sharks and stockpiling their fins without restrictions, while waiting for a NDF that would allow such exports. To the disappointment of the authorities and the shark fin industry, two hammerhead shark NDFs have since been issued (August of 2015 and March of 2017) by Costa Rica’s CITES Scientific Council, and both of them found that the export of hammerhead shark fins would be detrimental to the survival of the species. Frustrated by these results, the government asked the Costa Rican Fisheries Institute to provide a third Hammerhead Shark NDF, one that fits the exporter’s needs.

Meanwhile, at least ten tons of endangered hammerhead shark fins, from at least 15,000 sharks, are stockpiled in the port city of Puntarenas, waiting for the Costa Rican Fisheries Institute to lift the ban.

Arauz states that in order to abide by the spirit of CITES, hammerhead shark fins obtained during an export ban should always be illegal to export, and is pressuring the Costa Rican government to permanently ban the exportation of these fins and publicly destroy them. According to Arauz, this is the only way that a CITES Appendix II listing can translate into a positive conservation strategy for sharks. A petition supporting this may be found at this link:

https://www.change.org/p/costa-rica-don-t-export-that-stockpile-of-hammerhead-shark-fins

The situation violates the CITES listing which was intended to protect endangered hammerhead sharks from international commerce. Though the Appendix II listing bans the export of the fins, it permits the killing of the endangered species to continue unabated.

Arauz says, "The bottom line is that working as hard and as extensively as we have been here in Costa Rica, we have not had an impact on hammerhead shark mortality."

He explains that sharks are the main target of the long overfished Costa Rican mahi mahi long-line fishery, and with the price of fins as high as it is, a variety of loopholes are exploited to profit from them.

For example, the "fins attached" requirement, which specifies that a shark's fins must remain attached to the animal, resulted in fishermen landing the fins attached to just the spine. In other cases, fisheries licensed for other species may still bring in sharks and declare them as incidental catch. The mahi mahi season, for example, only lasts for four or five months, yet a mahi mahi fishery catches sharks throughout the year and claims them to be "incidental." But when sharks comprise 80 or 90 percent of the catch, it is actually a shark targeted fishery posing as a mahi mahi fishery.

Arauz is working for more protection for hammerhead sharks since they are already listed on CITES and are banned from international commerce. He is seeking a three month closure of all long-line fisheries in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, and has filed a court case regarding the stockpiling of shark fins, with hopes of obtaining a court order to ban the landing of hammerhead sharks.

Meanwhile, on May 18th, he won a court case mandating that hammerhead sharks are to be removed from INCOPESCA's official commercial species list. Being listed as a commercial species meant that hammerheads were not considered to be wildlife, so were not covered by wildlife conservation law. Thus, getting them back under the jurisdiction of Costa Rica’s Ministry of Environment (MINAE) and the Costa Rica’s CITES Scientific Council, is a big step. The next move planned is to have hammerhead sharks listed as being endangered under MINAE and to remove silky and thresher sharks from the commercial species list.

Arauz has become disappointed with the whole CITES approach which requires each species to be listed separately, as if the problem is monospecific, rather than address overfishing in terms of the overall damage to the ecosystem. Further, his efforts to list silky and thresher sharks at the last CITES event were not only opposed by Costa Rica, but by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as well. As explained earlier, an Appendix II listing does not actually ban international commerce, but allows it to occur under the criteria of sustainability. So, in practice, it is extremely difficult to implement and the FAO is a huge power to fight.

Small-scale fisheries

Costa Rican small scale fisheries support thousands of Costa Rican families who depend upon the health of its coastal waters. They still remember how good the fishing was in the 1980s, and report that now, in spite of a much greater investment of effort, they can scarcely make ends meet.

The depletion of coastal fish stocks was caused by a rampant shrimp trawling industry that was initiated in the 1950s. Trawlers are fishing vessels that drag a weighted net over the seafloor and effectively destroy its intricate and delicate habitat. The trawlers invade hammerhead nurseries and the pupping grounds of rays and silky sharks.

The coastal fisheries were depleted by the 1980s and as a result, Costa Rica invited a Taiwanese Mission to teach Costa Ricans how to fish with long-lines in the high seas, and make use of the fishery resources of its vast Exclusive Economic Zone.

This action sparked the beginning of the shark fin industry of Costa Rica. Before this, in Costa Rica and other South American countries, sharks were considered a bad type of fish and they were not targeted—no one ate shark. But under the influence of the shark fin trade, all that changed. Obligated to land fins “attached” to the bodies, the shark fin industry’s surplus meat was sold for domestic consumption. Now Costa Ricans alone are consuming about 2000 tons of shark meat a year. This is the problem with mandating a “fins attached” policy: it does not properly address overfishing.

Arauz did a study to determine how much the long-line fishery had declined over the last decades, and found that not only had the mahi mahi fishery declined by over 50%, but so have the numbers of silky sharks, as well as their size. Over 95% of silky sharks caught in 2010 had not attained maturity and those small silky sharks were pushed upon consumers.

To help restore the health of the coastal waters, with a coalition of Costa Rican NGOs, Arauz filed a law suit against the shrimp trawling industry, which was responsible for much of the destruction, in 2012.

The law suit succeeded and shrimp trawling was banned.

Though shrimp trawling was banned in 2013, the ban was not immediate—it involved a six-year phase-out. Now, only ten boats are actively trawling in Costa Rica, and the activity will stop completely by 2019.

The problem with the commons, Arauz explains, is that it is everybody's and nobody's. Though Costa Rican small scale fishermen understood the need to protect coastal reefs and wetlands, as long as the shrimp trawlers were coming through and killing everything no matter what they did, they were reluctant to cooperate in its protection. But now that shrimp trawling is almost at an end, progress is being made in helping the fishers to protect their reefs.

But now the FAO, and the UK-based NGO Flora and Fauna International, are supporting the Costa Rican government in the effort to get shrimp trawling restarted. Arauz has had to fight them for the past three years in court as well as in the Congress. The FAO has actually begun funding the Costa Rican government to do studies to try to make shrimp trawling sustainable.

Ending long-line fishing

There is currently an initiative from the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission's Scientific Committee (IATTC) that recommends closing long-line fishing in the eastern Pacific Ocean for three months, from July to September, to protect silky sharks from overfishing and to replenish their populations. Arauz found that a six month closure is needed, based on his own published study of long-lining, but he was glad to accept three months, anyway. However, the closure has been discussed at meetings for three years in a row, and each time, Costa Rica has blocked it.

"Imagine," Arauz says, "a three month closure of all long-line fishing in the eastern tropical Pacific. Imagine everything that would be saved."

Many sharks travel widely, and in adjacent countries they are not protected. Panama has some degree of protection and Arauz has a lot of support from the people of El Salvador and Guatamala where he and his colleagues have been going for years to do sea turtle work and train activists. But they have not been able to have any effect on putting policies in place.

"Its really tough in those countries," he explains, "And I can’t be as vocal in a foreign country as I am here, at home.”

Cocos Island's birthday

Cocos Island National Park, which is also recognized as a United Nations World Heritage Site, turned forty years old on June 22. The island has a 12 mile no take zone around it comprising 1,989 km2, and for the last four years Arauz has been working on getting the protected area enlarged to a rectangular area of 9,6450 km2. He and his colleagues have been negotiating for its protection, in spite of the opposition of shark fin exporters and the long-line fishery, with the intention of having the enlarged area included in the park as part of its anniversary celebrations.

Other nations that have been hard hit by the shark fin racket, including Brazil, Easter Island, and the Galapagos, are working on establishing and increasing their marine protected areas MPAs, so the enlargement of the Cocos Island National Park is the next step to take.

"What I want to see is fewer dead sharks," Arauz says, as he describes this new campaign. "Lets take areas away from the shark fishermen."

Arauz wants total protection from international commerce for sharks and shark parts, (in the way that sea turtles are protected) and to find a way to reduce the power and extent of fisheries. It is well known that factory fishing not only takes away the fish on which the small-scale fisher depends, but also drives up the price to export prices, so that the local people lose out in two ways.

In the meantime, he continues to fight for sharks, to try to get more species listed by CITES, and to make the CITES regulations work. He hopes that the recent court resolution will bring positive changes and that the policies of the new President of Costa Rica result in increased shark protection as well as full abidance to Wildlife Conservation Law.

Arauz remembers that, like sharks, turtles were once threatened, but were brought back from extinction's horizon through global conservation efforts and an international ban on their trade. He still dreams of such protection for sharks. And perhaps through the sheer power of his efforts and influence, and in spite of all corruption and opposition, the deadly trade in shark fins will finally be repulsed from the shores of Costa Rica and forced into retreat. ■

Ila France Porcher, author of The Shark Sessions and The True Nature of Sharks, is an ethologist who focused on the study of reef sharks after she moved to Tahiti in 1995. Her observations, which are the first of their kind, have yielded valuable details about their lives, including their reproductive cycle, social biology, population structure, daily behaviour patterns, roaming tendencies and cognitive abilities.

Download the full article ⬇︎