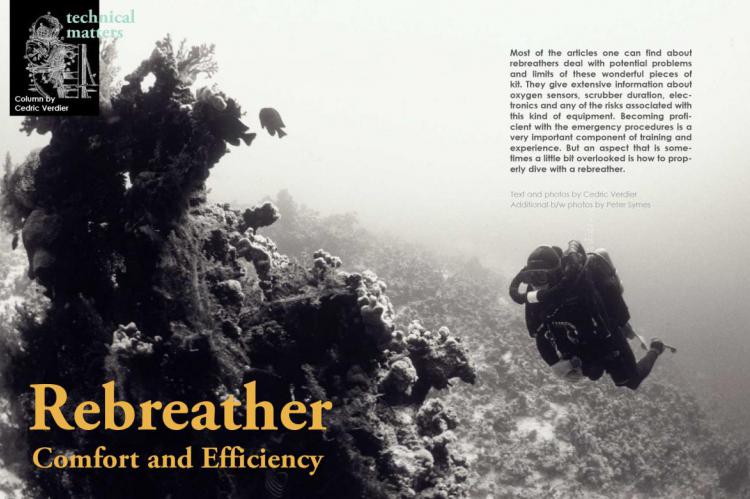

Rebreather comfort

Most of the articles one can find about rebreathers deal with potential problems and limits of these wonderful pieces of kit. They give extensive information about oxygen sensors, scrubber duration, electronics and any of the risks associated with this kind of equipment. Becoming proficient with the emergency procedures is a very important component of training and experience. But an aspect that is sometimes a little bit overlooked is how to properly dive with a rebreather.

Tags & Taxonomy

Being Streamlined With a Rebreather

Very often, one can see a lot of rebreather divers who don’t move in a very efficient way. They swim in a strange position, closer to the seahorse than to the manta ray. They spend a lot of energy fighting against the increased density of water, adding drag and turbulence to the necessary energy one has to spend for their propulsion. In one of his articles, Jarrod Jablonski states: “Resistance increases as the square of velocity. The energy required to overcome this resistance increases approximately as the cube of the initial energy required. What this means is that if one doubles the surface area of something, this results in a resistance that is four times the original resistance; in turn, this requires an increase in energy nearly sixteen times as great to offset the increase in resistance.” It simply means that a rebreather diver (and all divers in general) should work to reduce their surface area. An article published in DIVE Magazine a few years ago shown that lots of drag were simply created by hoses and danglies not as close as they should be to the diver’s body. The gas consumption of a CCR diver is directly proportional to their level of exertion. Using more O2 to move underwater means having a shorter dive time and a higher CO2 production. Both factors are counterproductive for a rebreather diver who wants to get all the benefits of using such a complex piece of equipment.Configuration and danglies

Most of the time, rebreathers look very bulky and messy. The technical rebreather diver has lots of hose and cable on their chest and their arms. Additional sling tanks and poor configuration don’t help to avoid the now popular astronaut-like image of the rebreather diver. It’s maybe satisfying to show that we can manage to dive with heavy and obviously very complicated equipment, but it’s definitely not streamlined and efficient. Handsets: most of the CCRs have one or two handsets that are attached to the diver’s forearm. A highly inelegant cable is connected to the electronics, most of the time on top of the canister or the housing on the back of the rebreather. Each rebreather diver should have someone else taking pictures or video of their configuration to see how poorly streamlined these handsets are. A better routing and maybe a chock cord loop at the appropriate location should help to keep the cables close to the body in any position (not only in a vertical position in front of a mirror!). SPG and LP hoses: in a similar way, a rebreather is full of hoses pointing downward or bulging out when the diver swims horizontally. Shortening the hoses is of prime importance if you want to have a better configuration. And of course, unnecessary hoses and components are like pimples on a fashion-model’s face: they should be immediately removed! Counterlung placement: OTS (Over-The-Shoulder) counter-lungs often look very cumbersome compared to the back-mounted counterlungs where the chest area is clear. Nevertheless, even OTS CLs rebreathers can be configured properly to diminish the cumbersomeness somehow. CLs can be adjusted very close to the body, almost under the armpits, without compromising the Work of Breathing and the diver’s comfort. Quite the opposite; when the diver has nothing on their chest, they can move more easily, closer to the obstacles or the bottom, with less drag and effort.Balance and trim

Being able to achieve a horizontal position at all time (slightly head down, feet up) is not one the cave/wreck diver’s dream. It should be the main goal for everyone, but it’s definitely not the case for a vast majority of the rebreather divers. A balanced rig would avoid the so common “butt-heavy” position. The ideal horizontal position mainly helps when you don’t want to silt up a place. Many divers think they are horizontal underwater; it’s, most of the time, not true. They are maybe horizontal when they swim but slowly (or quickly!) come back to a more vertical position as soon as they stop swimming. With a balanced rig you can stop close to the bottom and stay horizontal even while doing a specific and difficult task (tying some knots on a guideline, adjusting some settings on a camera/dive computer, helping another diver, etc). A balanced rebreather is sometimes quite difficult to achieve because most of the units have the heavy components on the bottom (valves, regs, etc) and the buoyant components on the top (counterlungs, wings, etc). online casino malaysia The first step is to work on the rebreather configuration: Cylinder and regs: Some rebreathers have the option to de-invert the tanks in order to shift some weight on top of the unit. Trim weight: The rebreathers with a case don’t have a lot of flexibility for their configuration. A trim weight can then be added on top of the unit to offset the unbalance. Wing and backplate: A short wing with more lift on the bottom than on the top is clearly a useful tool for a better trim. Counterlungs: the position of the CLs is obviously important but their size is also another factor to consider. A smaller volume and less gas (optimal loop volume) help to reduce the uplift component of the vertical vector. Then the second step is to see how the rest of the dive gear will interact with the rebreather. Dry or wet suit: a dry suit generally gives a better trim as it provides the diver with some additional buoyancy on the legs. It’s most of the time not the case with a wetsuit (specially at depth with the suit compression). Other equipments like pockets or heavy fins (ie JetFins) have also to be considered. Additional equipment: Most of the time, a rebreather diver will carry other pieces of gear like sling tanks and canister lights. The buoyancy characteristics of the tanks (full or empty) and the lights have to be thoroughly checked as they can easily ruin a good trim so difficult to achieve! Ask a friend who has a camera to spend some time with you underwater. Then, back to land, have some fun discovering what you actually look like. Spot all the danglies. Check what could be more streamlined. Go back diving and repeat the process till you become frozen. To speed up this process, a friend of mine even uses a big mirror in his pool. You directly see what could be adjusted and immediately try! Like a dancer in a ballroom.Mastering Buoyancy Control with a Rebreather

So, let’s assume that the trim is now a problem of the past. The next step is Buoyancy. Buoyancy control is an essential element of diving proficiency; it is also one of the hardest skills to master, especially with a rebreather. You have to control the gas in the wing, the dry suit, the breathing loop. You have to take into account the suit compression at depth, the buoyancy characteristics of the tanks when empty ...Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #16

PHILIPPINES - Diving the Visayas. AMBON - the spice islands in Indonesia. Protecting the Sharks: Wolfgang Leander + Rob Stewart/Sharkwater movie. Divemedicine: Why antioxidants protects divers. NEW Zealand - land of the Kiwis. Rebreathers: Comfort and Efficiency. WHY shoot video. SPRING DIVE Fashion. Science: The Black Sea. New Equipment. Report from Moscow.