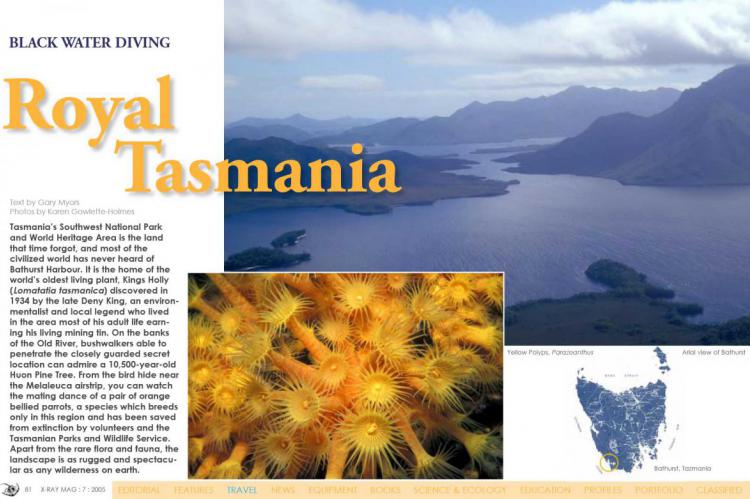

Royal Tasmania

Tasmania’s Southwest National Park and World Heritage Area is the land that time forgot, and most of the civilized world has never heard of Bathurst Harbour. It is the home of the world’s oldest living plant, Kings Holly (Lomatatia tasmanica) discovered in 1934 by the late Deny King, an environmentalist and local legend who lived in the area most of his adult life earning his living mining tin.

On the banks of the Old River, bushwalkers able to penetrate the closely guarded secret location can admire a 10,500-year-old Huon Pine Tree. From the bird hide near the Melaleuca airstrip, you can watch the mating dance of a pair of orange bellied parrots, a species which breeds only in this region and has been saved from extinction by volunteers and the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service. Apart from the rare flora and fauna, the landscape is as rugged and spectacular as any wilderness on earth.

Tags & Taxonomy

The Territory

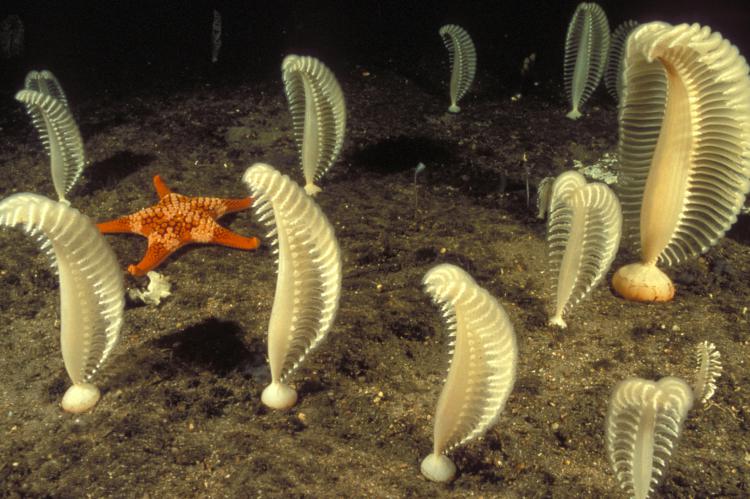

Port Davey and Bathurst Harbour makes up a large and ecologically significant part of the Tasmanian World Heritage Area. The TWHA covers 20 percent of the Island State and encompasses a greater breadth of natural and cultural values than any other World Heritage Area on Earth, according to the Tasmanian Department Primary Industries Water and the Environment (DPIWE). The waterways were formed as the sea level rose after the last ice age flooding the river valleys with seawater, and the huge volume of black, tannin-stained freshwater flowing from the numerous rivers forming a dark freshwater layer over the top of the seawater. The freshwater layer, usually 2-6m thick, is so dark from the tannin that little light penetrates it. Below the tannin layer, the seawater is very clear but dark even on the sunniest of days, the light levels are so low that you cannot see without dive torches. This gives rise to a rare phenomenon called “deep water emergence”, where species usually found in deepwater (100m +) are found in much shallower water due to the low light levels.

In the Bathurst Channel, this phenomenon is enhanced due to Breaksea Island in the mouth of the Channel sheltering the Channel from wave action, so that the seafloor in the Channel is not only dark, it is also relatively calm—mimicking conditions on the “shelf-break”, the edge of the continental shelf and upper slope in depths of 80-200m, and the marine life we find living in the Bathurst Channel is typical “shelf-break” species. The Bathurst Channel/Harbour area is unique in a world context, a place where the unique southern Australian shelf-break species can be seen and studied in safe diving depths.

The first expedition

On our first expedition in 2002 for a smaller Japanese television company, we spent ten days diving and filming in almost perfect conditions. All equipment and personal were flown into the remote Melaleuca airstrip. Seven Cessna flights transported the team of eight Japanese, two Eaglehawk Dive Centre staff and the two Southern Explorer crew. It was a logistical drudge with the weather playing a significant part in delaying our departure from Hobart for the best part of two days. Flying conditions can change within minutes of locating the isolated airstrip adding unnecessary cost by returning to Hobart.

This expedition was different from many points of view: bigger budget, smaller crew, and most importantly, departing Hobart aboard the vessel we were to use for the duration of the stay in Bathurst Harbour. The abalone mother ship ODALISQUE was our chosen live aboard. She is a modern 18-metre aluminum vessel able to accommodate 12 passengers and crew in comfort, a large back deck with cradles for 15ft and 17ft aluminum dinghies, and two holds that kept our equipment and extra provisions below deck out of the weather.

The expected duration of twenty days in the wilderness required extensive and careful planning. To cater for five Japanese, two marine biologists, myself as dive guide and the ODALISQUE’s crew of three (skipper, deckhand and cook) in a remote region that can only be reached by sea or light aircraft and is subject to extremes in weather, we had to be very well organized. We even took a washing machine. While the Japanese were over-equipped not knowing the isolation of the location, we managed to find a place to stow everything and to sail from Hobart at the appointed time. We had advised the film crew that we might have to wait in Recherché Bay if the weather on the south coast was as bad as forecasted by the Bureau of Meteorology. It was a little lumpy rounding Whale Head, but the vessel handled it well, and only a couple of the film crew took to their bunks.

We made a brief stop at Maatsuyker Island to film the huge colony of between 1000-1500 Australian fur seals at The Needles on the south side of the majestic rock that is home to a couple of volunteers who look after the heritage-listed light house and buildings.

The whole expedition nearly finished on that first day when Tomita, the cameraman, nearly drowned his digital beta-cam camera while traveling at dangerous speed in the dinghy in pursuit of a shot. Despite the conditions, Tom still managed to shoot some useable footage before the journey westward continued.

After a journey of about eight-hours from Hobart that included the stop at Maatsuyker Island, we entered beautiful Spain Bay near the entrance to the Bathurst Channel an hour before sunset and anchored for the night. Our chef, Johnno, knocked up a first class meal, and we were in bed reasonably early expectating an early start and a busy first day in Bathurst Harbour.

Karen Gowlett-Holmes, one of Eaglehawk Dive Centre’s marine biologists, and I were acting as guides for this expedition. Karen had done a number of scientific research field trips to the area with CSIRO prior to our last filming expedition the previous year. I had worked in the area on several occasions during my ten years as an abalone diver. So, we were well acquainted with the difficulties of extended diving in such a remote location.

The Bathurst Channel

The Bathurst Channel has several heavily wooded islands that offer shallow water diving in beds of sea whips as shallow as 4m depth—these are usually at least 35m deep. We had a surprise when we entered the water—we found that the tannin layer was almost non-existent.

There had been a prolonged drought in the area, which usually has rain virtually every day, and the flow of tannin-stained water from the surrounding rivers had dropped to a trickle. Usually, this site has a four to five metre deep dense tannin layer (like very strong black coffee) that blocks out all daylight and makes each dive as dark as night, but this time the tannin layer had become very diluted (looked like weak tea) and at depth, it had the appearance of diving on a dull day.

We had a run of superb weather for ...

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #7

BALI - visiting Tulamben. Science: Salt of the sea. Conservation: Mangrove. Polluce wreck. The first frogment. The Techni-sub story. Royal Tasmania. Portfolio: A tribute to Michael Portelly. Technical matters: Going solo or not? Photography: Manipulation? Ecology: Anemone city Profile: Miranda Krestovnikoff. Science: Drinking seawater