Scapa Flow: Centenary of the Scuttle of the Imperial German High Seas Fleet

One hundred years ago this year, on 21 June 1919, 74 warships of the Imperial German Navy High Seas Fleet were scuttled en masse at Scapa Flow, the deep natural harbour set in the Orkney Islands of northern Scotland that was the WWI base for the Royal Navy Grand Fleet. The scuttle was the greatest single act of maritime suicide the world has ever seen.

The 74 German warships had not been surrendered—they had been interned at Scapa Flow under British guard seven months earlier as a condition of the Armistice, which had halted the hostilities of the Great War in November 1918.

The majority of the sunken German warships were salvaged in the 1920s and 1930s, but three 25,390-ton König-class battleships—König, Kronprinz Wilhelm and Markgraf; three 5,531-ton light cruisers—Dresden, Cöln and Karlsruhe; the 4,315-ton minelaying cruiser Brummer and the 924-ton torpedo boat destroyer V83 were left on the bottom, along with the four great 1,020-ton 15-inch gun turrets of the battleship Bayern and assorted masts, spotting tops, guns, pinnaces and other pieces of ships deemed not worthy of salvage. This profusion of submerged German WWI naval history has made Scapa Flow a world-renowned dive location—a “must” for serious wreck divers.

By late 1918, Germany had almost lost her major allies and her land forces were being pushed back on the Western Front. Large numbers of American troops had begun to arrive, and a sailors’ revolt had begun during October, which had lit the fuse of revolution. The civilian population was starving as a result of the Royal Navy blockade of the North Sea from its Scapa Flow base.

The Armistice

German military leaders were pressing for surrender terms with the Allies, but the High Seas Fleet had survived the war relatively intact and therefore, as a condition of the Armistice of 11 November 1918, 74 of the newest ships of the High Seas Fleet—ten battleships, six battlecruisers, eight cruisers and 50 destroyers—would be interned at Scapa Flow with their guns disarmed under close British guard until a final peace agreement was reached. In effect, the High Seas Fleet was being held hostage.

With the Armistice finally called on 11 November 1918, the five battlecruisers Seydlitz, Moltke, Von Der Tann, Derfflinger and Hindenburg; the ten battleships Baden, Bayern, Friedrich der Grosse, Grosser Kurfürst, Kaiser, Kaiserin, König, König Albert, Kronprinz Wilhelm, Markgraf and Prinzregent Luitpold; the six light cruisers Cöln, Dresden, Emden, Frankfurt, Karlsruhe and Nürnberg; the two mine laying cruisers Brummer and Bremse; and fifty 900-ton torpedo boats began to arrive at Scapa Flow under Allied guard and were moored up in neat rows.

The bulk of the German crews—some 20,000 sailors—were then repatriated to Germany, leaving only skeleton care-taking crews. The warships, although under Allied guard, remained German property and there were no British guards on board. The ships were prohibited from flying the Imperial German Navy ensign—with its black cross and eagle—and all wireless receivers had been taken away. The ships were cut off and isolated from Germany.

The First Battle Squadron of the British Grand Fleet of five battleships, two light cruisers and nine destroyers was stationed at Scapa Flow and would keep a watchful eye on the 74 interned German warships.

Peace negotiations

The peace negotiations dragged on without resolution from November 1918 through the winter of 1918/19, into the early summer. The once proud grey German warships slowly became streaked with surface rust and marine growth from their long stay at anchor.

The British provided the Germans with four-day-old newspapers, in the belief that nothing sensitive could be gleaned from them. These papers were avidly read by the German sailors as they were one of the few means they had of keeping up with what was going on in the outside world. The German sailors were not allowed ashore and could not obtain any information from local sources.

After seven months of negotiation, the Allies gave the Germans five days—ending on 21 June—to accept their peace terms, failing which a state of war would exist again. On 20 June, the German commander Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter read the German counter-proposals to those Allied peace terms in the latest four-day-old newspaper, The Times of 16 June. The Times of 17 June was then delivered—and this carried the official response of the Allies to the German counter proposals.

The Allies had refused to accept any of them, and from the British speeches reported in The Times, it seemed to von Reuter that there was little chance of a peace deal being agreed. He felt it likely that the Armistice would end on 21 June and a state of war be resumed—and that the British would then immediately seize the precious but powerless vessels of his Fleet. With only skeleton crews aboard and all guns disarmed, the seizure of the most modern and powerful ships of the High Seas Fleet could not be prevented—he could not let that happen. (The Armistice had in fact been extended by two days, to 7 p.m. on Monday 23 June—but after the scuttling, von Reuter claimed he had not been advised of this; the British counter-claimed that he had been told. The jury is still out on that one).

At 9 a.m. on the morning of 21 June 1919, the British First Battle Squadron left Scapa Flow for the first time in the seven long months of internment, to carry out a long-range torpedo-firing exercise at sea. They were under orders to be back in Scapa Flow by the extended deadline of 23 June to deal with any trouble that might arise should the Armistice not be further extended. A small guard-force of three British destroyers—Vegar, Vesper and an unserviceable destroyer, Victorious—was left behind.

Giving the order to scuttle

At 10 a.m., von Reuter, now apparently believing that war would restart that day, appeared in full dress-uniform on the quarterdeck of his flagship, the light cruiser Emden. He could hardly believe his luck when he learned that the British guard squadron had left the Flow on exercise earlier that morning.

At 10:30 a.m., a string of command flags appeared over Emden, even though this was well outside the set times permitted by the British for issuing signals. The order read: “PARAGRAPH 11. BESTÄTIGEN”—which translates to “Paragraph 11. Confirm.”

This simple command was the pre-arranged coded order to the commanders of the other ships in the Fleet to initiate the scuttling of their vessels. Unbeknownst to the British, for the last four days, von Reuter’s trusted officers and sailors on each of the ships had been taking steps to ensure a speedy and unstoppable scuttle if this order was given. Doors and hatches had been secured in the open position—some being welded open—so that the ships would flood more easily. Seacocks had been set on a hair turning and lubricated thoroughly. Large hammers had been placed beside any valves that would allow water to flood in if knocked off, and bulkhead rivets had been pried out.

Now that the order to scuttle had been given, seacocks were opened and disconnected from the upper deck to prevent any British boarding parties from closing them if they boarded before the ship went under. Seawater pipes were smashed, and condensers opened. As valves and seacocks were opened, their keys and handles were thrown overboard, so that they could never be closed again. Once the vessels started to scuttle, there was no way to stop the ships sinking other than by taking them in tow and beaching.

The signal to scuttle was repeated from ship to ship by semaphore and by Morse code on signal lamps—and travelled slowly around the German Fleet. The southernmost ships of the long lines of torpedo boats were not visible from the Emden, and it took a full hour before the order reached them.

The pre-arranged responses started to come back slowly—the first reaching Emden at about 11:30 a.m., just as the original signal to scuttle reached the last of the destroyers: “PARAGRAPH ELEVEN IS CONFIRMED.”

In a patriotic gesture of defiance, many of the German ships ran up the Imperial Navy ensign at their sterns. The prohibited white flag, with its bold black cross and eagle, had not been seen at Scapa Flow before. Others ran up the red flag, the letter “Z,” which in international code signalled: “Advance on the enemy.”

Sinking ships

At noon, an artist who had hitched a ride on one of the patrolling Royal Navy drifters to sketch the German Fleet at anchor noticed that small boats were being lowered down the side of some of the German ships, against British standing orders. He alerted a British officer, but only 16 minutes later, the first of the warships to sink—the former flagship of Admiral Scheer at the Battle of Jutland, the Kaiser-class battleship Friedrich der Grosse—turned turtle and went to the bottom. Hundreds of German sailors now began to abandon their ships into lifeboats.

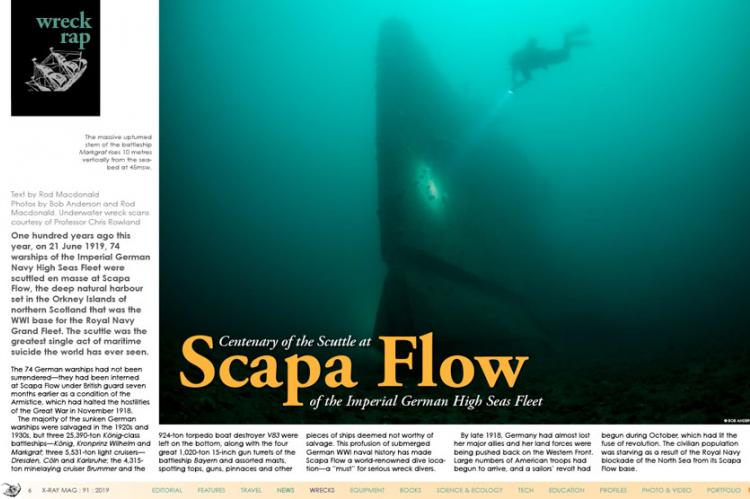

Some of the great warships settled into the water on an even keel, whilst others rolled slowly onto their sides. Some went down by the bow or stern, forcing the other end of the ship to lift high out of the water. The top-heavy battleships moored in deeper water listed and then turned turtle as they sank. Those ships moored in shallower water settled onto the seabed, leaving their masts, top hamper and smokestacks standing above the water’s surface.

The German ships began to sink in quick succession. Of the battleships, König Albert disappeared at 12:54 p.m., Kaiser at 1:25 p.m., followed closely by the almost simultaneous sinking of Prinzregent Luitpold and Grosser Kurfürst five minutes later at 1:30 p.m. Kaiserin went at 2 p.m., followed 30 minutes later by Bayern at 2:30 p.m.

The first of the battlecruisers to sink was Moltke at 1:10 p.m. On the nearby battlecruiser Seydlitz, the entire crew stood proudly to attention on the deck singing the German national anthem and watching as Moltke sank beside them. The crew of Seydlitz then had to abandon their own ship, and 40 minutes later at 1:50 p.m., Seydlitz followed Moltke to the bottom.

As each ship sank, a whirlpool was created in which debris swirled around, slowly being sucked inwards and eventually being pulled under into the murky depths. Oil escaping from the submerged ships spread upwards and outwards to cover the surface of the sea with a dark iridescent film. Scattered across the Flow were lifeboats, hammocks, lifebelts, chests, spars, gratings and all the debris of a ship’s passing.

British response

When it was realised that the entire German High Seas Fleet had started to scuttle, Sir Sydney Fremantle, now far out to sea with the First Battle Squadron, was advised and he immediately ordered his Squadron to return to Scapa Flow at full speed.

The two serviceable British guard destroyers Vegar and Vesper fired warning shots with their main guns and fired with machine guns and small arms as they closed. Three German sailors in a lifeboat containing 13 men were killed and four were wounded. The others were ordered back aboard their ships and forced by threats of further shooting to turn off the flood valves.

At 2 p.m., the vanguard vessels of the British First Battle Squadron, returning at full speed from their aborted exercise, entered Hoxa Sound, the main entrance to Scapa Flow from the south. Many of the German capital ships were already at the bottom of Scapa Flow, whilst those remaining afloat were in the advanced stages of sinking.

One Royal Navy destroyer immediately broke off from the Squadron and using explosives, cut the anchor cable of Reuter’s flagship, Emden, and successfully towed her to the shore where she was beached. Other British destroyers fired warning salvoes of shells from their main guns. Armed boarding-parties went aboard the battleship Baden where they managed to restart the diesel generation units, restoring power and lighting, and enabling systematic pumping to start. She was driven ashore and beached in Swanbister Bay in sinking condition.

A British drifter put an armed boarding-party aboard the battleship Markgraf to try and stop her flooding. The Markgraf’s captain, Lt-Cdr Walther Schumann, delayed as long as he could before emerging to meet the boarding party waving a white flag. He refused to obey an order from the boarding-party to have his own men go below and shut off the flood valves or to allow the Royal Navy boarding-party to do so. The British boarding-party attempted to force their way below decks to halt the scuttle. A scuffle broke out in which Schumann was shot through the head and died immediately, and another officer was seriously wounded. But enough had been done to ensure Markgraf went to the bottom at 4:45 p.m.

Here and there, small ship’s boats full of German sailors rowed through the flotsam, and in each, a sailor held a single white flag. Elsewhere, empty lifeboats rocked in the calm sea. Every now and then, a bubble of trapped air would escape from one of the submerged ships to break the surface and reveal the position of the ship below. British patrol boats moved slowly around, sometimes taking wallowing lifeboats in tow. Of the capital ships, only Baden would fail to be sunk.

WWI’s last German POWs and casualties

The 1,744 now homeless German officers and men were sent to prisoner-of-war camps in the north of England. After seven months incarceration, on 29 January 1920, von Reuter and the remaining POWs were taken by train to Hull, where they boarded the German steamship SS Lisboa, which took them home across the North Sea to Wilhelmshaven. They were the last German POWs of World War I to be repatriated—14 months after the rest of the combatants laid down their arms on Armistice Day, 11 November 1918.

The 13 German sailors who had been shot that fateful day, 21 June 1919, were the last casualties of the First World War, which ended on 28 June 1919—seven days after the might of the German High Seas Fleet had sunk dramatically to the bottom of Scapa Flow.

Salavage

The majority of the scuttled German warships were raised intact in the coming decades, in a monumental feat of ground-breaking salvage work that would be hard to replicate today. Those ships left, that we dive today, were considered to be in water too deep or to be sitting at difficult angles that made sealing all their openings for lifting by compressed air impractical.

Prolific wreck site

Today, the historical importance of the High Seas Fleet ships that were left, coupled with the many other shipwrecks in the area, make for one of the world’s most prolific wreck sites. After all, where ease can you dive three German WWI dreadnought battleships and four cruisers all lying in depths suitable for recreational scuba divers?

When you come to dive Scapa Flow, you are immediately struck at what a centre for diving Orkney is. When you step off the ferry from the mainland at Stromness, you will see the harbour packed with rugged but well-equipped dive boats with groups of divers of up to 12 aboard, each fettling over their kit. Racks of scuba cylinders and closed circuit rebreathers of every variety line the kitting up benches on dive decks whilst compressors clatter away, filling tanks for the next day’s dive.

Scapa Flow attracts divers from all over the world, but there are so many wrecks that there is never any diver saturation on a particular wreck. Most times, you have the wreck to yourself. It takes years to get to know the German shipwrecks properly, to become familiar with these amazing shipwrecks, and to understand the sense of history that still pervades Scapa Flow both beneath and above the waves. ■

Rod Macdonald is the author of the book, Dive Scapa Flow, published in 2017 by Whittles Publishing Ltd. Available on Amazon.

Download the full article ⬇︎