Shooting Below Decks

Not all sunken ships are the same. There are shallow wrecks, deep wrecks, very old barely discernable wrecks, wrecks sunk in war, wrecks sunk to make artificial reefs, even wrecks placed on the sea bed for Hollywood movies. While each ship has a different history and characteristics they share one thing in common—they all have been transformed into undersea time capsules.

Tags & Taxonomy

The ship’s design reflects how life at sea existed in a particular era, and personal effects that went down with them signs a personal signature to those that walked and worked the decks. Even vessels placed intentionally on the bottom as man-made reefs, often have glorious histories contained within their hulls that can be felt by the astute diver during a visit.

As artificial reefs, they tend to attract, and ultimately, possibly sire their own population of critters from encrusting invertebrates to apex predators. Between the assemblage of marine life and the ships themselves there’s no shortage of photographic opportunities. The emphasis of this article will be on bringing back meaningful images from inside the passageways and compartments—AND do it as safe as possible. In no shape or form is this piece intended to be an all-encompassing text on wreck penetration or photography, but merely a primer of some things to think about.

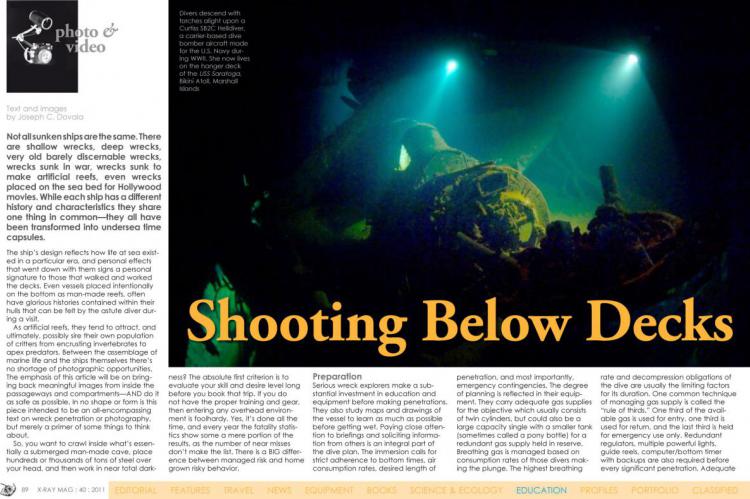

So, you want to crawl inside what’s essentially a submerged man-made cave, place hundreds or thousands of tons of steel over your head, and then work in near total darkness? The absolute first criterion is to evaluate your skill and desire level long before you book that trip. If you do not have the proper training and gear, then entering any overhead environment is foolhardy. Yes, it’s done all the time, and every year the fatality statistics show some a mere portion of the results, as the number of near misses don’t make the list. There is a BIG difference between managed risk and home grown risky behavior.

Preparation

Serious wreck explorers make a substantial investment in education and equipment before making penetrations. They also study maps and drawings of the vessel to learn as much as possible before getting wet. Paying close attention to briefings and soliciting information from others is an integral part of the dive plan.

The immersion calls for strict adherence to bottom times, air consumption rates, desired length of penetration, and most importantly, emergency contingencies. The degree of planning is reflected in their equipment. They carry adequate gas supplies for the objective which usually consists of twin cylinders, but could also be a large capacity single with a smaller tank (sometimes called a pony bottle) for a redundant gas supply held in reserve.

Breathing gas is managed based on consumption rates of those divers making the plunge. The highest breathing rate and decompression obligations of the dive are usually the limiting factors for its duration. One common technique of managing gas supply is called the “rule of thirds.” One third of the available gas is used for entry, one third is used for return, and the last third is held for emergency use only. Redundant regulators, multiple powerful lights, guide reels, computer/bottom timer with backups are also required before every significant penetration.

Adequate cutting tools—at least two, are a must as well. Besides the cables, ropes, lines, etc., that most sunken wrecks are “equipped” with before they are sunk, there most likely will also be a nice selection of fishing line, anchor line, nets, and maybe even diver guide lines left behind by visitors after sinking. A sharp blade for ropes and nylon lines and a pair of shears for cables, wires and other metals need to be added to the wreck diver’s kit.

Technique

Techniques and skill development are as important, if not more so, than having the proper gear. Buoyancy and propulsion techniques have to be mastered before swimming inside overhead environments. These two diving inherent skills, while not overly difficult, do require effort and practice. Far too many certified divers, including “advanced” c-card holders, show a lack of ability in this department. Ricocheting off the deck with fins and arms flapping all over the place is not a pretty picture and becomes dangerous quickly in a confined space. Even a small amount of silt kicked up will pretty much negate any chance of capturing good images. The nuances of buoyancy control apply to the entire dive team.

Ideally, you want as horizontal a position as possible without needing to do excessive hand or foot movement to maintain it. This can be achieved through shifting a small portion of ballast weight around the body as needed. For instance, if your feet float, you can shift a couple of pounds to the lower legs with ankle weights. If head up is a problem, you can put a few pounds on the upper portion of the air tank. A combination of BC jacket weight pockets and a belt will also spread some of the weight around. Make sure to pay attention to roll, as a little too much lead or gear on one side or the other can make it very difficult to stay right side up.

With the plethora of weighting options available to us today it has never been easier to achieve balance in the water. If you can maintain a horizontal position with a foot or two of water beneath you without stirring up or crashing into the bottom, you’re buoyancy skills are in excellent shape.

Flailing arms and legs are the single biggest enemy of keeping the water clear inside a wreck, so being proficient with your fins is far better if it’s not an after thought. Large kicking sweeps suitable in open water have no use inside a confined space. A number of other fin movements such as the “modified flutter” work well and still give adequate propulsion. The legs are bent at the knees and only the ankles are used to power the fins, the thighs are kept stationary. Another popular method is the “shuffle kick” where again the knees are bent upward and you use small sideways motions with the calves bringing both legs out and then back in together.

The key is small efficient movement as far away from sediments as possible. Hand movements are also controlled with only gentle minimal sculling or a single finger used to keep balance. Wildly swinging arms will not only dislodge sediment (or a buddy’s mask), but also give you a fairly decent chance of having to rummage through the first aid kit after the dive because of skin to steel impact. The wreck diver’s mantra, indeed every diver’s mantra, should be to keep your hands to yourself and know where your fins are.

Configuration

It is not only the dive kit that needs special attention for penetration but also the camera configuration. Long multiple arm sections on strobes might be great for open water wide angle but inside a ship they can be grabbier than a drunken frat boy. A single arm on each side works far better. Keeping the strobe arms collapsed parallel with the camera housing body helps to keep a low profile while navigating passageways and hatches.

I find that keeping just enough tension on the flash arm joints to keep them in place works best. This way, it’s a simple matter of pulling them into position and collapsing them again without having to constantly fumble with the ball clamps. Unless ....

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #40

Malta’s Gozo Island (Mediterranean) by Scott Bennett | Wrecks on Kwajalein atoll | Valentines Gifts for Sea Lovers edited by Gunild Symes & Catherine GS Lim | Kamchatka, Russia by Andrea Bizyukin, PhD | Dive Medicine: Diving & Risk by Dr Carl Edmonds | Ghostfishing The Netherlands by Peter Verhoog | Portfolio: Alex Vanzetti by Gunild Symes | Nassau, Bahamas: Hollywood Underwater by Millis Keegan | The Apps Are Coming by Peter Symes | Channel Islands, California by Matthew Meier | UW Photo: Shooting Below Decks by Joseph Dovala