Snoots

When I began shooting underwater 15 years ago, the underwater photography world was much smaller than it is today. Traveling with oodles of slide film, being restricted to 36 exposures per dive, and requiring an intimate understanding of how light works are just a few factors which kept underwater imaging from being widely popular.

Tags & Taxonomy

What was once a very niche hobby, pursued only by the most determined and passionate individuals, has now become almost as common as scuba diving itself. Okay, maybe that’s a bit of an over-exaggeration, but my point is that the digital revolution has caused an explosion in the number of underwater photographers in the last several years.

Image hosting websites (i.e. Flickr, Smugmug, Picasa, etc.), personal websites and social networking sites have all provided outlets for images to be easily shared with the world. Since photography is often an inspiration-based art, and since there are so many images available at one’s fingertips, there is a tendency for images to be imitated—yawning frogfish, pygmy seahorses, silhouetted divers pointing a torch, soft corals hanging from mangrove roots… the list goes on and on. Your photos will blend in with the crowd, unless you do something different. You can either hope for a trip filled with high-impact subjects, or you can put a different photographic spin on ordinary subjects.

Enter the snoot.

What is a snoot?

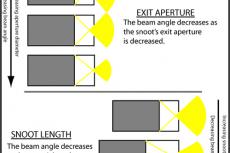

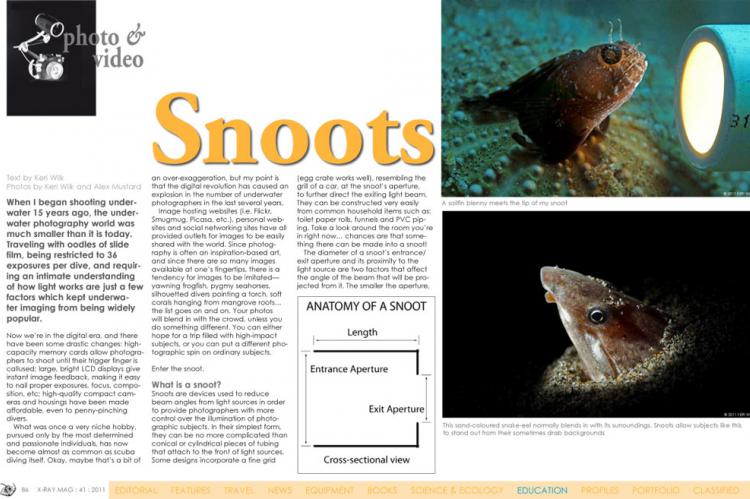

Snoots are devices used to reduce beam angles from light sources in order to provide photographers with more control over the illumination of photographic subjects. In their simplest form, they can be no more complicated than conical or cylindrical pieces of tubing that attach to the front of light sources. Some designs incorporate a fine grid (egg crate works well), resembling the grill of a car, at the snoot’s aperture, to further direct the exiting light beam. They can be constructed very easily from common household items such as: toilet paper rolls, funnels and PVC piping. Take a look around the room you’re in right now… chances are that something there can be made into a snoot!

The diameter of a snoot’s entrance/exit aperture and its proximity to the light source are two factors that affect the angle of the beam that will be projected from it. The smaller the aperture, and farther away it is, the narrower the beam—and vice versa.

The intensity (energy per time per area) of a snooted light beam is highly dependent on the reflectivity of the internal surfaces of a snoot. When constructed from highly reflective materials (white colour, or mirrored), it’s possible to create a more concentrated light beam than the un-snooted strobe, so battery life can be prolonged. Conversely, when constructed from highly absorptive materials (black), you may need to boost the strobe power to maximum in order to obtain well-illuminated images.

Background

Light-shaping tools such as umbrellas, baffles, grids, diffusers, reflectors and snoots, are commonly used by studio photographers. The restrictions imposed by an underwater environment make some of these tools much less practical for underwater photography.

Snoots, in particular, have been experimented with by many underwater photographers and videographers on their strobes and video lights. To my knowledge, most of them have had mixed success, and usually abandoned them out of frustration after a few failed attempts.

Their main drawback is the time and effort required to aim them correctly. For those who do most of their shooting in tropical destinations, the thought of “wasting” several dives trying to light a subject just right isn’t the most appealing idea. For these reasons, snoots have been regarded more as novelties than as useful tools, and have stayed under the radar.

About a year ago, I started doing my own experimentation with snoots. The nervous tick in my left eye, and the bald spots scattered over my head attest to the notorious difficulty of aiming them… but the results were shockingly worthwhile. Now, you’d be hard-pressed to find me diving without my beloved homemade snoots.

Why use a snoot?

—Isolate the main subject

Since a snoot greatly restricts a strobe’s beam angle, light can be projected exactly where you want it, eliminating distracting background/foreground elements or giving a spotlight effect. Photographers often strive to create images with black backgrounds to make the subject in the foreground “pop”, but it’s sometimes difficult to prevent strobe light from hitting the background as well. The use of a snoot can solve this problem.

Minimize backscatter

Backscatter is seen in images when stray strobe light illuminates suspended particles between the camera’s lens and the subject. By snooting a strobe, you decrease the beam angle, make it easier to control stray light, and minimize backscatter. ...

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #41

Special coverage of the Cayman Islands by two renown residents -- take a tour with Cathy Church and Lawson Wood to Cayman Brac, Little Cayman, Stingray City and the new artificial reef of the USS Kittiwake off Grand Cayman Island.

Don Silcock takes us to the mystical haven of Halmahera in the Maluku Islands.