'SS Polynesien' poster launched a centenary after she sunk

We are living in a golden age of wreck diving. A hundred years ago today, we were in the final months of WWI.

The Battle of Amiens or the Third Battle of Picardy had just commenced (8 August 1918). This Allied attack would later became known as the ‘Hundred Days Offensive’ and this action ultimately led to the end of the First World War.

Seventy-five years ago today, we were in the midst of the Second World War. Consequently, several of the wrecks we currently dive in European waters are casualties from these two great wars.

As technology evolves, so does the face of warfare. We no longer consider a fixed bayonet as a primary weapon, instead we use unmanned drones to fight our battles. The likelihood that we shall again see an immense naval battle, or a wolf pack of submarines hunting and sinking a merchant convoy are extremely slim. For the diving fraternity, it means that our enormous wreck heritage will never be so rich again.

How long will these wrecks last before mother nature takes them back?

Divers will often speak about how a certain ship looked “before the superstructure collapsed,” or “before the wreck was damaged in the storms of a certain year.” I can instantly think of a classic example of this: the SS James Eagan Layne. This Liberty Ship was torpedoed and beached off Plymouth, England in March 1945. I have dived her on and off for more than 20 years, and I have watched her gently evolve from wreck into wreckage.

Recording our heritage

Wreck heritage is documented using various methods, including verbal recordings, dive logs, drawings, cinematography and photography. We are no longer constrained by 24 or 36 very precious film exposures. Digital photography has been hugely liberating, allowing divers, scientists and researchers to document wrecks in better detail.

With the advent of GoPro cameras, cinematography is also far more accessible, and it has meant that the wrecks we love are being captured and megabytes of video data are uploaded to social media channels on a regular basis. Whilst this is all useful data, a photograph or piece of footage can generally only capture a small part of a hunk of rust. So how else can we document wrecks?

In recent years, 3D cinematography and photogrammetry has developed and these are both useful methods of recording wrecks.

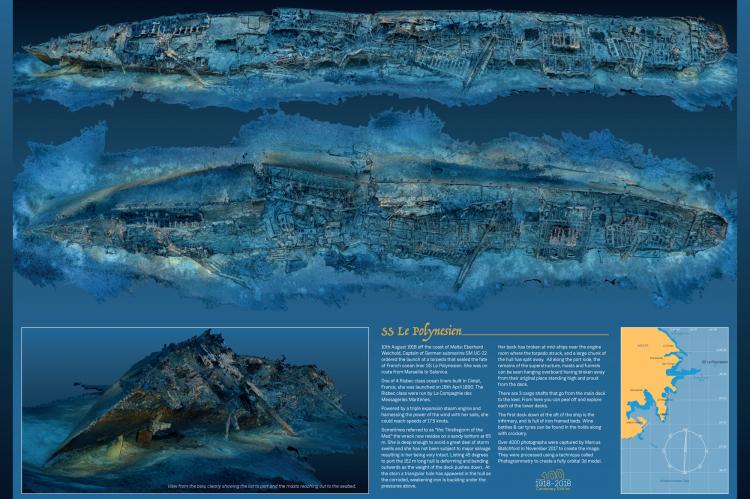

Marcus Blatchford, a British underwater photographer, has been using photogrammetry to document a number of Maltese wrecks, including the MV Rozi, Schnellboot S-31, HMS Hellespont and the bow section of HMS Southwold. Probably the most interesting Maltese wreck is the mighty SS Le Polynesien, and Blatchford has been involved with a project to record this wreck in high definition 3D. (If you click on the link, you will see four models: the stern gun, the anchor windlass and two models of the complete wreck).

SS Le Polynesien

A hundred years ago today—on 10 August 1918—Captain Eberhard Weichold ordered the crew of SM UC-11 (a mine-laying submarine) to torpedo the Polynesien. The 152m (498ft) French steam and sail powered passenger liner was hit on the port side near the engine room and sank within 20 minutes. A number of reports state that 11 crew members and six passengers died.

One century on, this massive wreck now lists to port, in an area where salvage is illegal. The Polynesien is still very much intact and in great condition. She is deep enough to miss most storm surges, hence it is possible to see exactly what is actually happening as the structure degrades. However, not every diver will be able to visit this beautiful wreck—she is a technical dive because she lies at 43–65m (141–213ft).

Marking the centenary

A centenary should always be acknowledged and marked. Maltaqua, Marcus Blatchford and Steve Jakeway have therefore collaborated to create two limited edition fine art prints, and a full-colour poster showing detailed 3D images of the wreck of SS Le Polynesien.

Follow this link and click on 'Poly100' to order your print.