Subsurface Noise

How the snapping shrimp makes itself heard.

You might expect the oceans below the surface to be a quiet and still place, they are far from being so.

Tags & Taxonomy

If we ignore the anthropogenic noises such as those made by ships and oil-rigs, and the natural noises made by waves and surf, earthquakes, calving icebergs, etc, there is still a considerable amount of noise, which emanates from the aquatic invertebrates and fishes.

Source of the noise

Among the more than 25,000 species of living fish, it is claimed by Dr Rodney Rountree of the University of Massachusetts, USA, that there are more than 700 known vocal fish species in the world. It is not only in the tropical waters that these vocal fishes are to be found. More than 40 species exist in the cool waters around Cape Cod, for example, including the toadfish, sea robin and the striped cusk-eel. The cusk-eel produces croaking sounds of between 500 and 1800 Hz, and the toadfish, Porichthys notatus, produces a humming noise at 80 – 100 Hz, which is so loud that it can even be heard on the shore. Even the male haddock, Melanogrammus aeglefinus, advertises for a mate using a series of increasingly rapid low thumps.

So, all these fish can be very noisy indeed but how do they actually produce their sounds?

Sound production in fishes

Some fish noises from the Croakers (Sciaenidae) are made by muscles that stimulate the animal’s swim bladder, which then amplifies the sound. The toadfish, mentioned above, rapidly contracts muscles in its swim bladder at 100 times per second to produce the loud humming. Other fish, for example the Grunts (Pomadasyidae), grind teeth close to their pharynx, the sound from which again is amplified by the swim bladder.

The swim bladder or, more accurately, the gas bladder, is a gas-filled sac located in the dorsal region of the fish. It contributes to the ability of the fish to control its buoyancy, and thus enables it to stay at a given depth. It also enables it to ascend or descend without swimming, and thereby conserving energy. Fish like the sole, though, who live on the sea bed, don’t have swim bladders.

This ability to function as a sound amplifier is yet another example of an organ developed by evolutionary forces for one purpose, that of efficient swimming, becoming available to use for another, that of amplification of sound. Gas bladders are evolutionarily related to lungs.

Noisy though the fishes and aquatic mammals are, it is perhaps the invertebrates that are the greatest noise makers of them all.

The noisy invertebrates

Among the marine invertebrates, the crustacea are those that employ strong sound signals in several different ways. We are talking here of the crabs, lobsters, shrimp, etc. Most marine invertebrates produce sound by stridulation i.e. the rubbing together of two parts of the body, just like grasshoppers do on dry land by rubbing their hind legs against the leathery forewings. An example of this is the spiney lobster, Palinurus elephas, which rubs its attennae together to produce ...

(..)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #19

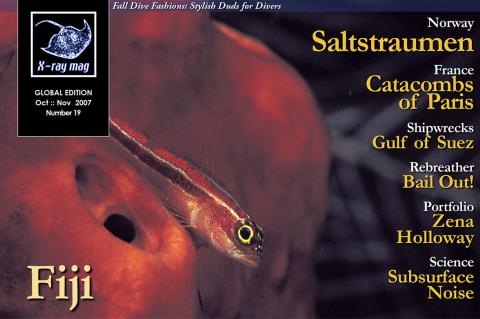

FIJI: Scott Bennett went to the far side of the Pacific and got the Royal treatment. Red Sea: Wreck hunter and author Peter Collings shows what all the latest craze is all about.

Our Norwegian friends takes us for spin in Saltstraumen, the most powerful drift dive on the planet - so buckle up.

Find out where all the noise in the Ocean come from and check out the Fall dive fashion before we go visit SeaCam and have a talk with Harald Hordosch about what it takes to become successful. Cerdic Verdier explains how to Bail out on a rebreather.

And finally Michel Ribera takes on a very spooky dive in the Parisian Netherworld - come see what the Catacombs hold. The Grande finale is presented by Zena Holloway - some amazing photography there.