Unlocking the secrets of the Greenland Shark

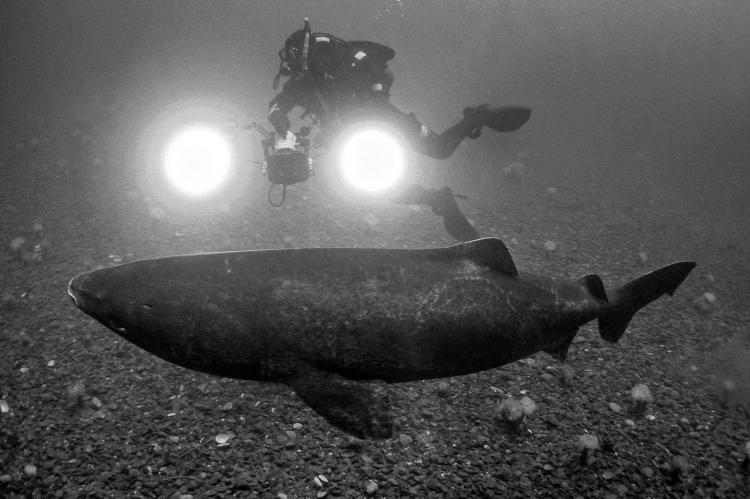

One of the dreams of any naturalist is to be the first to find and detail the life of a hidden or unknown animal first hand. Since 2003, scientific divers with the Greenland Shark and Elasmobranch Education and Research Group (GEERG) have begun to unravel the mysterious life of the Greenland shark, which at over seven meters in maximum body length and exceeding a ton in weight, is the second largest carnivorous shark after the great white.

Primarily a deepwater shark of the northern boreal oceans, Somniosus microcephalus is the only shark that patrols beneath the ice of the Arctic Circle. Hundreds of thousands of these sharks have been caught in directed fisheries, and yet little is known scientifically about the species. As GEERG scientists, we have been engaged in non-traditional research since 1998 of the ecology and behavior of the Greenland shark in order to elucidate some of the mysteries surrounding this enigmatic animal.

Historical aspects

The Greenland shark was well known to the Inuit peoples of Canada’s Arctic, Greenland and Scandinavia, who hunted it through ice holes using bait and lanterns as a light attractant. Once lured to the surface, the sharks were harpooned or simply hauled from the water. The Inuit used the hide, teeth and flesh and called the shark, “Skalugsuak”. In an ancient legend, the shark originated from a urine soaked rag used to wash an old woman’s hair that blew from her head, fell into the sea and swam away in the form of the shark.

The Inuit noted the shark’s pungent smell, and that dogs fed with its meat became intoxicated and even died. This poisoning is due to very high levels of trimethylamine oxide, an osmotically active product of nitrogen metabolism found in high concentration in the shark’s flesh where it is neurotoxic when eaten.

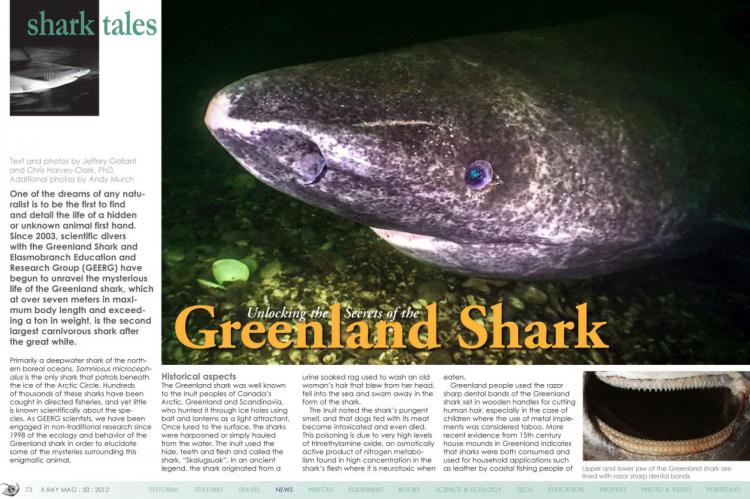

Greenland people used the razor sharp dental bands of the Greenland shark set in wooden handles for cutting human hair, especially in the case of children where the use of metal implements was considered taboo. More recent evidence from 15th century house mounds in Greenland indicates that sharks were both consumed and used for household applications such as leather by coastal fishing people of Nordic origin.

In more modern times, peoples of Iceland and Greenland learned to ferment shark meat to destroy the toxin, and this “shark cheese”, known as Hákarl, is a pungent and prized delicacy in Iceland where it is washed down with an equally powerful locally made liquor called Brennivin.

Commercial fisheries for Greenland sharks have existed since the late 19th century, and Arctic whalers from Scotland noted the presence of hundreds of these voracious sharks around freshly killed whale carcasses during flensing and trying out operations. One of the earliest scientific drawings of a Greenland shark was made to illustrate whaler Captain William Scammons 19th century treatise on marine mammals, showing the shark with its characteristic spiracle and a copepod parasite attached to the eye.

By the late 19th century, an artisanal fishery for Greenland sharks had developed in coastal communities in northern Scandinavia, Greenland and Iceland, primarily for their livers. The huge organ (up to 150 kg) was placed in a container and would naturally ferment and separate into an oil-rich layer that could be extracted and used as a fuel for lamps, or could be rapidly rendered using heat to make a more pure form of combustible oil.

Modern times

The North Atlantic fishery for Greenland sharks peaked in the early 20th century when up to 32,000 tons per year were harvested. The fishery failed as fossil fuels became the chief source of inexpensive light and heat. In the latter part of the 20th century, Inuit people on Baffin Island developed ice fisheries for Greenland halibut, and found that Greenland sharks consumed their catch if gear was left in the water for too long. Scientist Aaron Fisk estimated several hundred sharks a year were killed as bycatch in this fishery.

Longline vessels in the winter fishery for Atlantic halibut off the coast of Nova Scotia have reported occasional catches of large Greenland sharks as bycatch, as have bottom trawl fisheries in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Beck and Mansfield reported in the 1960s on Greenland shark depredation of Inuit net-based fisheries for narwhal, with spectacular photos of the lesion created by shark bites on the whales.

Biological aspects

The natural history of the Greenland shark is not well understood. A handful of publications exist in the scientific literature, and these have mostly focused on geographic distribution, diet and stomach contents, as well as the eye parasite that infects these animals.

The Greenland shark is large, heavy-bodied and has a reduced first dorsal fin, small second dorsal, smaller D-shaped pectoral fins, and a large, paddle-like heterocercal tail equipped with a water splitting caudal peduncle. The ground colour of the shark can vary from grey to mottled grey and white to dark brown or black; it's lighter on the underside. The skin is extremely rough, with large visible dermal denticles that easily cause lacerations when handling the animal.

The eyes are large with a pucker at the caudal corner and a prominent reflective tapetum that glows green in dark conditions when a light is shone on it. The head has large nares terminally, and the upper and lower surfaces of the head are liberally covered with electrosensory ampullae. The mouth is underslung and hard to visualize unless the observer is at the same level or underneath the animal. It is relatively small compared to the large size of the shark. When closed, the lower dental band is not visible. When open during ram ventilation or feeding, the band everts and becomes visible ...

(...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #50

Papua New Guinea: Kimbe Bay, Witu, Milne Bay, Tufi, New Ireland; The Greenland Shark; The Arrow, Nova Scotia; Timor-Leste's Tasi Tolu; Sheck Exley on Mix; Diving with Humboldt Squid; Safety Culture in Diving; Dive Fitness: Are You Scuba Fit? Point-and-Shoot Underwater Photography; Underwater Dogs by Seth Casteel. Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, turtle news, shark tales, whale tales and much more...