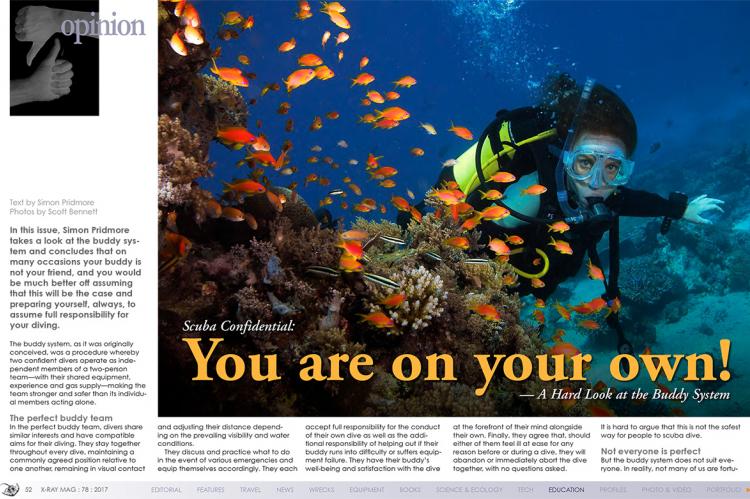

You are on your own! A hard look at the buddy system

In this issue, Simon Pridmore takes a look at the buddy system and concludes that on many occasions your buddy is not your friend, and you would be much better off assuming that this will be the case and preparing yourself, always, to assume full responsibility for your diving.

Tags & Taxonomy

The buddy system, as it was originally conceived, was a procedure whereby two confident divers operate as independent members of a two-person team—with their shared equipment, experience and gas supply—making the team stronger and safer than its individual members acting alone.

The perfect buddy team

In the perfect buddy team, divers share similar interests and have compatible aims for their diving. They stay together throughout every dive, maintaining a commonly agreed position relative to one another, remaining in visual contact and adjusting their distance depending on the prevailing visibility and water conditions.

They discuss and practice what to do in the event of various emergencies and equip themselves accordingly. They each accept full responsibility for the conduct of their own dive as well as the additional responsibility of helping out if their buddy runs into difficulty or suffers equipment failure. They have their buddy’s well-being and satisfaction with the dive at the forefront of their mind alongside their own. Finally, they agree that, should either of them feel ill at ease for any reason before or during a dive, they will abandon or immediately abort the dive together, with no questions asked.

It is hard to argue that this is not the safest way for people to scuba dive.

Not everyone is perfect

But the buddy system does not suit everyone. In reality, not many of us are fortunate to have found the perfect dive partner and be able to dive with this person all the time. It is also naive to expect that one diver can immediately develop this sort of symbiotic relationship with another diver simply by being paired up with them at random.

Yet, this is what commonly happens in organized sport diving, where many operators act as if, just by instructing two divers to dive together, you thereby create a buddy team. On the contrary, this sort of policy can cause misunderstandings or bad feelings, and generate scenarios that place divers at risk.

For example, there are many divers who object to being told that diving alone or as part of a loose group is not permitted. However, when forced to accept a buddy by the operator they are diving with, they will not say anything, as they know they will not be allowed to dive at all if they refuse. So, they just adopt a policy of passive resistance and remain silent. However, they have no intention of taking any notice of their buddy at all once they are underwater.

This produces one of two results: either the two divers each go their own way, deliberately refusing to acknowledge the other’s existence, or one diver just ends up resentfully following the other around, largely ignored but unilaterally ensuring they stay together. There is absolutely no safety benefit at all in either case. Both divers would be much less stressed and much more willing and able to help each other if the buddy system had never been mentioned and if they had just been allowed to dive as self-sufficient members of a loose group in the first place.

Other divers will seek out operators that enforce a buddy protocol and abuse the system by choosing to interpret it as an opportunity to absolve themselves completely of responsibility for their dive and place the burden entirely on the shoulders of another diver. Their companion will often have no idea that they are playing this role.

Sometimes, two people with this mindset unwittingly end up diving together, a sure-fire recipe for disaster as, even if something minor goes wrong, the stress of the event will be compounded when they both realize that, far from having someone close by to save them, each of them is effectively alone.

Divers die alone

Defenders of the buddy system argue that a diver is more likely to come to harm if they are alone than if they are with another diver. The statistics support this contention, showing that most divers who die diving, indeed do die alone. However, a closer examination of the reports shows that, in most cases, the diver who came to grief did not actually start the dive on their own.

Sometimes, problems occur when one diver has a problem and the other leaves them to surface alone. Or they ascend together, but then one descends again to continue the dive solo. Inattention and indifference can also leave a diver isolated. This happens, for instance, when one diver leads from the front, forgets to look back, and does not notice when the diver behind develops a problem.

Simply pairing divers up, therefore, is not a universal panacea.

Going solo

It may sound strange, but many problems with the buddy system would be solved if all divers were capable of solo diving and allowed to dive solo. Now, when I say “solo”, I am not suggesting that people should scuba dive alone, aloof and unapproachable. Human beings—and divers, in particular—are social animals. We like to share our experiences and we also derive a great deal of valuable emotional security from the company of others. There are a number of circumstances, too, when it is very useful to have another diver around—for example, if you lose your mask or get stung by marine life.

What I mean by solo diving, rather, is an approach whereby you dive in a team of two, three or more but prepare for every dive as if you are diving alone and never undertake any dive that you would not be completely comfortable doing on your own. The concept is that you, and only you, are ultimately responsible for your safety on every dive. You never put yourself in a position where you are not able to survive a dive by trusting your own knowledge, equipment and self-rescue skills, whatever happens.

Equipment thoughts

This approach involves carrying self-rescue equipment, a cutting tool and devices like a light, a whistle and a delayed surface marker buoy. It also involves having an accurate idea of your air consumption rate and making sure that you are prepared to deal with an out-of-air emergency, a regulator free-flow or a blown hose or O-ring, occurring at any point in the dive. On deeper dives, this will mean you need to carry a genuine alternate air source, such as a pony bottle.

Solo mindset

Most importantly, you have to adopt a solo diving mindset. A key prerequisite for this is honest introspection. Before you embark on any dive—whether alone, with a partner or in a group—you need to be able to conduct an objective, truthful assessment of your own capabilities and state of mind. Here is a short checklist.

You only commit to doing any dive if ALL the following circumstances apply:

- You genuinely want to do the dive.

- You have identified all the potential risks.

- You are equipped to deal with anything that might happen.

- You have practiced what you will do in the event of an emergency.

- You have real-life experience of successfully handling stress underwater on similar dives.

- You have the discipline to stay within the dive plan.

- You have the discipline to resist following another diver who does not abide by the dive plan.

- You have the discipline NOT to change the plan on a narcosis-fueled whim halfway through the dive.

- AND you have the discipline to abort a dive as soon as something goes wrong or you feel ill at ease.

Here are three examples to illustrate what I mean by "the discipline to abort":

Example #1: You are on a night dive when one of your two lights fails and you switch to your back-up light. You abort the dive at this point because you are now diving with one light and if that fails too, you have none.

Example #2: You are coming out of a shipwreck recovering your reel and line when the line jams around the reel. You now have two problems, the reel and the decompression clock. Rather than sit at depth trying to unjam the line, you tie the reel off and follow the line out of the wreck, keeping to your dive plan. You can always do another dive to recover the reel later when you do not have a decompression burden and such a limited gas supply.

Example #3: You are on a deep dive when you begin to develop a sensation that something is wrong, although you cannot identify a specific problem. Rather than continue and hope the feeling goes away, you cut short your dive and concentrate even harder than usual on executing a perfect ascent.

Solo is safer

By adopting solo diving techniques, you make yourself immune to the vagaries of the buddy system. Instructors can also teach their students these techniques and make sure they do not perceive the buddy system as an excuse for not taking responsibility for their own dive. Then perhaps, with more solo-capable individuals around, operators will trust divers more and stop enforcing a system that just does not work. ■

Simon Pridmore is the author of the international bestsellers, Scuba Confidential: An Insider’s Guide to Becoming a Better Diver, Scuba Professional: Insights into Sport Diver Training and Operations and Scuba Fundamental: Start Diving the Right Way. He is also the co-author of diving and snorkeling guides to Bali and Raja Ampat and Northeast Indonesia. This article is adapted from a chapter in Scuba Confidential. For more information, visit: SimonPridmore.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎