Aqaba: Diving Jordan's Artificial Reefs

My relationship to the Middle East is like a long-running but complicated love affair. I keep being attracted to it and keep coming back. Each time I step out of the airplane when I arrive there, I am embraced by a pleasant, complex, and—dare I say—almost sensual scent so full of notes, most of which I have never been able to identify. There seems to be a whiff of charcoal and smoke from shisha (the molasses-based tobacco concoction smoked in a hookah) mixed in with scents of spices, flowers, trees and the sun-baked sand. It is a very characteristic compound smell, which I find pleasant. Also, people are just nice and welcoming.

Tags & Taxonomy

I have always felt reassuringly safe in Jordan—which is in stark, but nice, contrast to the impressions frequently painted by the press that makes a living reporting on strife. It does frequently torment me, not only that lasting solutions to the conflicts elsewhere in the region remain so elusive, but also that these headlines tend to discolour the general perception of what the region has to offer visiting travellers—which is a lot.

Jordan remains one of my personal favourites, not just because I always feel comfortable there, but also because of the treasure trove of historical sites and landscapes that can be found to supplement and contrast the diving. The atmosphere here has a timeless feeling to it, transcending centuries. The passing of time is felt, yet it seems to stand still. One passes through the rhythms of the day rarely glancing at a watch.

I am just as much a dive geek as the next, but I really enjoy the majestic expanses of the red Wadi Rum desert—which is even more spectacular if you can watch the sunrise or sunset painting it in delicate rosy, pink and purple hues. The tranquillity of the desert just seems to seep into one’s soul, soothing the spirit. Time easily seems to come to a standstill or has little meaning. And after nightfall, the starry sky is as clear as it can get. Gazing at the stars and the Milky Way arching across the sky never gets old.

The hidden city of Petra, a UNESCO World Heritage site just a two-hour drive from Aqaba, continues to intrigue me—even more so after reading a book on its history, putting it into a wider context. One has to be completely ignorant not to appreciate how much history has taken place here. But I digress. This is, after all, a story about diving, so let me get on with it.

Dive sites

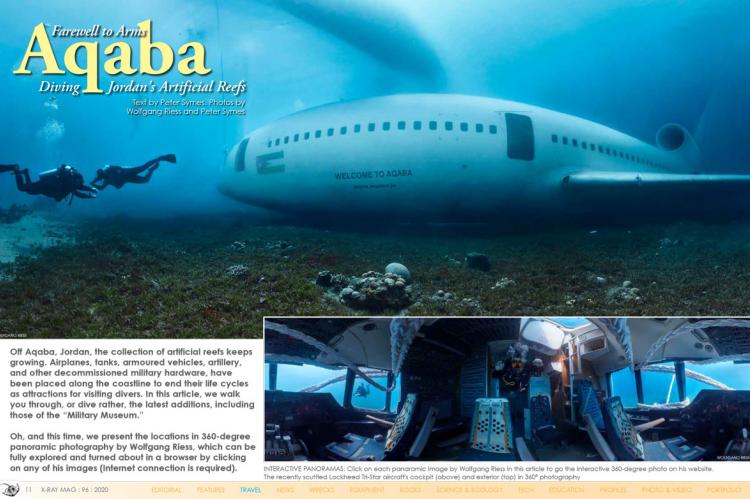

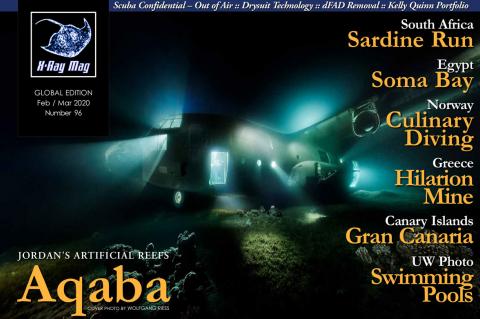

Perhaps the main defining characteristic of diving in Aqaba today is the ever-budding collection of artificial reefs, onto which additional aircraft and vehicles are steadily being added. The latest addition was the Lockheed Tristar, the scuttling of which we reported in issue #93.

Cedar Pride. The sequence of wrecks, purposely sunk to become attractions for divers, started off by accident with the wreck of the Cedar Pride, a freighter that caught fire while at port in 1982. It was damaged beyond reasonable repair, so it was scuttled a couple of years later to become an artificial reef. I suppose one thing led to another, and eventually various ex-military hardware such as the “tank,” which is actually an armoured self-propelled anti-aircraft gun battery, was scuttled in shallow waters.

C-130 Hercules. Then the C-130 Hercules, a former four-engine propeller transport aircraft donated by the Royal Jordanian Air Force, was scuttled under much media frenzy in November 2017, in fairly shallow waters close to the aforementioned tank. In fact, both dive sites and that of the nearby shipwreck of Al Shoruk can all be visited on the same dive. The C-130 aircraft is a model that has been operated by more than 60 nations, and more than 2,500 have been built since the aircraft first took flight in 1954. The newest version, the C-130J Super Hercules, is still in production. The sunken Hercules rests on a sandy seabed at a depth of just 12-17m, which provides ample time for underwater photography during the shallow dive. It is easy to penetrate and explore inside and out.

Military Museum. Following the sinking of the Hercules came the sinking of a growing collection of ex-military hardware, comprising a couple of Vietnam War-era Cobra combat helicopters, a Chieftain battle tank (known as Khalid Shir in Jordan), self-propelled anti-aircraft batteries, armoured personnel carriers, a tracked ambulance and various other vehicles with wheels or tracks. This collection is also known as the “Military Museum.”

In July 2019, a total of 19 former military machines were placed along the coral reefs and positioned to imitate a tactical battle formation. They have been placed in a location with little coral growth and not much marine life. Eleven of decommissioned pieces of military hardware were settled in the 20-28m depth range, and the remaining eight are at depths of 15-20m. The scuttling took seven working days, to ensure that the whole process did not affect the surrounding marine environment. The placement of these vehicles serves to both alleviate pressure on the natural coral reefs from increased tourism and to create new artificial reefs as well as dive sites.

The Military Museum is indeed unlike any other dive site I have ever seen. No location I am aware of has such a collection of artificial reefs in one spot. It is not an overly complicated dive. It is not very deep, there is little to no current, and it is close to shore in a quite sheltered position. That said, one should never be complacent, since mishaps can also happen in shallow water and on easy dives.

Beach and boat access

The artificial reefs off Aqaba are placed so many can be reached from the beach or at least by a short boat ride from the port, which is probably the most comfortable and convenient means of getting you and all your kit to the dive site anyway. Being on a boat also means you have a safe place for all your stuff—and they serve lunch. The location at the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba is very sheltered, so I cannot imagine that there are ever days where divers “blow out.”

Diving

Huey Cobra. As soon as I jumped in, I could see one of the Huey Cobra helicopters right beneath me. How odd to descend upon and hover above a helicopter, which usually is the thing that does the hovering overhead. Cobras were in use during the later stages of the Vietnam War and have been regularly featured in war movies and documentaries. The Cobra remains in service in several countries.

I had never seen one this close up. Granted, it had been stripped of its weapons, radome and other bits and pieces. In other words, it essentially had all its fangs and claws removed, but there it was—a machine that has seen active combat. This is a much better use, I think—making peace (and reefs), not war. As I swam about and gazed inside the narrow cockpit, it struck me how compact it was—like a sports car. The surrounding seabed was quite dull though—unsurprisingly, I might add, since a dull spot was deliberately chosen for the Cobra’s sinking to avoid impacting any living reefs.

Howitzer. Next in line was a M115 203mm (8in) howitzer—a type of artillery that sits at a slant with its barrel pointed skywards. For some reason, I could not help feeling that there was something defiantly dignified about this structure as it was now forever confined to its watery grave where it will surely never see another conflict but still insists on pointing its barrel towards a virtual enemy which will never come. The M115 saw US service in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

Chieftain tank. As I moved forward in a northerly direction parallel to the coast, the shallower parts of the reef in which the group of tanks and other vehicles had been placed in battle formation came into clearer view. The Chieftain tank was a massive vehicle weighing in at around 55 tons and equipped with a large 120mm gun. It was the main battle tank of the United Kingdom from the 1960s to 1980s and is still being operated by several countries—including Jordan’s armed forces. The Chieftain found a large export market in the Middle East where it saw all of its operational experience, including the largest tank battle of the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88). The Chieftain also fought at the Battle of the Bridges during the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

And so it went, as I swam from one piece of military hardware to the next. One can hover around all these pieces of aircraft and vehicles in three dimensions as if one was playing some computer game, except that this installation remained completely still and frozen in time, slowly becoming overgrown with coral and algae. It is a fun and unique dive during which one is constantly reminded of the folly of Man. The structures also provided ample opportunity to play with light at night, which Wolfgang Riess’ images on these pages demonstrate all too well. So, doing underwater photography on a night dive is up next.

Night dive

After enjoying a delicious barbeque aboard the dive boat while the sun set across the Sinai Peninsula on the other side of the bay, we rigged up for a night dive as the Military Museum. The sight of a bunch of underwater photographers, intensely focused all at the same time, was something to behold.

Nobody talked as cameras were checked and loaded up with full batteries, and housings were rechecked one extra time. Lamps were hung or placed on the seabed just behind the helicopters, which provided an eerie and ghostlike silhouette. I got all my gear set, was checked by a buddy and went in the water with a muted splash.

My first task was to get the camera properly configured. I had strobes mounted and ready to fire, but upon taking a test shot, I saw that given the size and distance to the subjects, my strobes mostly produced a haze of backscatter, which completely ruined the shot. So, I decided to switch them off and figure out which camera settings would best cope with the very low light conditions.

Photography challenges

I am talking about night photography with 25m of water overhead. I needed a shutter speed that was fast enough to freeze action and capture a sharp image but an ISO low enough to avoid images from becoming too noisy (grainy). Meanwhile, three-dimensional structures, such as the helicopter with its blades sticking out, really called for closing down the aperture to get a decent depth of field. This was a bunch of conflicting requirements. One or more had to suffer.

I was using my mirrorless Sony A7RII, as it has some pretty good low light capabilities, which go a long way. It also has IBIS—sensor stabilisation—which helps reduce camera shake at slow shutter speeds. However, objects that move will still blur at slow shutter speeds. So, IBIS is mostly useful with static subjects and not in images of divers moving about like Energizer bunnies on too much coffee. So, I went for a combination of settings, which I gathered would be the optimal compromise.

As it is not easy to look through a camera at night, in particular when wearing a dive mask and peering through a camera inside a housing, I had to rely on autofocus. In fact, I could not make out a damn thing, aside from some blotches of light on my camera’s back LCD—my eyesight has definitely become middle-aged, struggling in low light.

The camera apparently also struggled to find focus, as I could frequently hear the lens hunt for focus—moving back and forth without locking onto anything. That I was descending in free water without any downline or fixed reference, trying to maintain a steady slow decent with only a few visual clues—such as periodically looking up towards the boat while trying to keep the camera pointed in the right direction and getting the chopper properly framed—was a piece of real hard work and full-fledged multitasking.

It got a wee bit easier at depth, as the pressure differential got incrementally smaller. I got a better bearing on the helicopter as I moved closer. The tricky part was sensing my buoyancy and keeping it steady despite having so few references. Unsurprisingly, several shots were not in focus, or not where I wanted them to be. The depth of field was not something to brag about either. But I managed to pull off several keepers.

That is how it often goes in challenging situations. One has to prepare as best as one can beforehand and then improvise as circumstances turn out to be different than anticipated.

On the contrary, Wolfgang Riess, who was on the same dive, just nailed it as it appeared. Hats off to him. He has turned 360-degree imagery into a high art form. I am thus only happy to cede the bulk of the stage in this article to him, so-to-speak. I appreciate meeting someone who is more skilled or cleverer than I am in some particular area or field. It is inspirational and an opportunity to learn something new (well, at least in principle, because I will most likely not have the time nor the opportunity to practise this specialised skill set).

Ending notes

Getting back to the night dive, I swam around the dive site for the duration and ended up with a decent collection of useful shots before it was time to ascend. Looking up, I could see the moon silhouette the dive boat above me. What a magnificent evening. The day, and my short but joyous visit to Aqaba, was about to come to an end.

After cleaning up and disassembling our gear, we gathered for a last dinner together on the beach in front of the excellent Kempinski Hotel, which was one of the best I have stayed in over the years. The dinner, which included some Jordanian specialties, was simply stellar. And the talk among us, as musicians played, a belly dancer performed and we enjoyed our beers, was all about pictures and photography techniques. What else would you expect when a group of photo nerds gather around a table? Until next time. ■

Download the full article ⬇︎