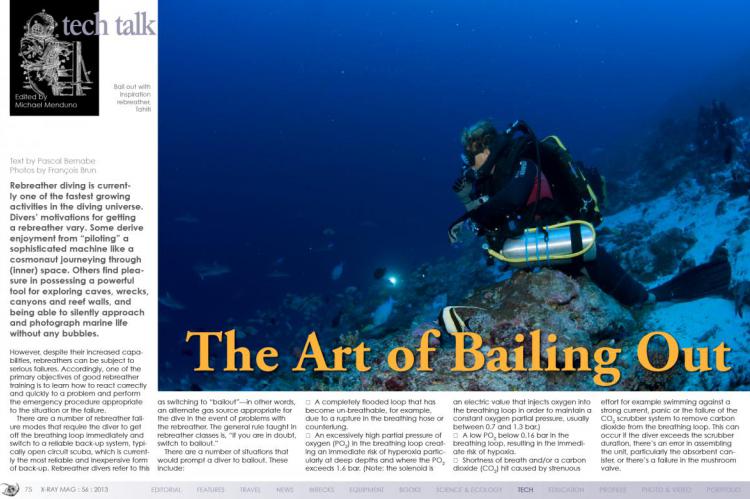

The Art of Bailing Out

Rebreather diving is currently one of the fastest growing activities in the diving universe. Divers’ motivations for getting a rebreather vary. Some derive enjoyment from “piloting” a sophisticated machine like a cosmonaut journeying through (inner) space. Others find pleasure in possessing a powerful tool for exploring caves, wrecks, canyons and reef walls, and being able to silently approach and photograph marine life without any bubbles.

Tags & Taxonomy

However, despite their increased capabilities, rebreathers can be subject to serious failures. Accordingly, one of the primary objectives of good rebreather training is to learn how to react correctly and quickly to a problem and perform the emergency procedure appropriate to the situation or the failure.

There are a number of rebreather failure modes that require the diver to get off the breathing loop immediately and switch to a reliable back-up system, typically open circuit scuba, which is currently the most reliable and inexpensive form of back-up. Rebreather divers refer to this as switching to “bailout”—in other words, an alternate gas source appropriate for the dive in the event of problems with the rebreather.

The general rule taught in rebreather classes is, “If you are in doubt, switch to bailout.”

There are a number of situations that would prompt a diver to bailout. These include:

- A completely flooded loop that has become un-breathable, for example, due to a rupture in the breathing hose or counterlung.

- An excessively high partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) in the breathing loop creating an immediate risk of hyperoxia particularly at deep depths and where the PO2 exceeds 1.6 bar. (Note: the solenoid is an electric value that injects oxygen into the breathing loop in order to maintain a constant oxygen partial pressure, usually between 0.7 and 1.3 bar.)

- A low PO2 below 0.16 bar in the breathing loop, resulting in the immediate risk of hypoxia.

- Shortness of breath and/or a carbon dioxide (CO2) hit caused by strenuous effort for example swimming against a strong current, panic or the failure of the CO2 scrubber system to remove carbon dioxide from the breathing loop. This can occur if the diver exceeds the scrubber duration, there’s an error in assembling the unit, particularly the absorbent canister, or there’s a failure in the mushroom valve.

- A complete failure of the electronics (PO2 display and heads up display) making it impossible for the diver to know the PO2 in the loop.

- Running out of onboard oxygen and/or diluent.

- The failure of two or more oxygen sensors. In this case, the diver can no longer be sure of his or her PO2 (when three cell voting logic is used).

The general rule for bailout is that there should be enough of the appropriate gas to ascend to the surface while allowing for a safety margin. For example, the rule used in cave rebreather diving, that is also applicable for decompression diving, is to calculate one’s consumption rate based on 30 l/minute (1.1 ft3/min) multiplied by 1.5 for a safety margin or 45 l/min. (1.6 ft3/min.

Experience shows that in the case of getting short of breath or CO2 intoxication, the gas consumption may rise to as much as 70 l/min (2.5 ft3/min) during the first minute and to lower to some 25 l/min (0.9 ft3/min.) during the following minutes. ( ...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #60

Indonesia's Gorontalo; Cayman Brac; Antarctica; Brazil's Fernando de Noronha; New Dalarö wreck park in the works in Sweden; Reviewing Poseidon's SE7EN rebreather; The art of bailing out; Idiot buddies; Safety culture; Scuba Confidential; Sensational snoots; Overview of photo editing software; Seacam Academy; Florida's artificial reefs; Erika Pochybova-Johnson portfolio; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, shark tales, whale tales and much more...