Belgian Mines of Mons

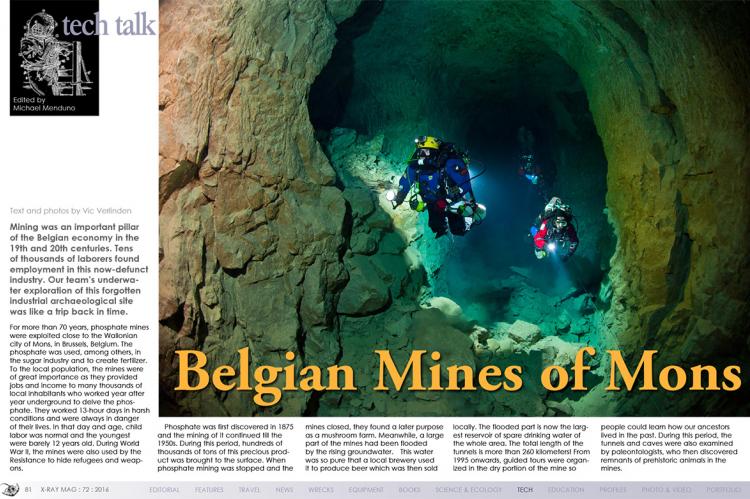

Mining was an important pillar of the Belgian economy in the 19th and 20th centuries. Tens of thousands of laborers found employment in this now-defunct industry. Our team’s underwater exploration of this forgotten industrial archaeological site was like a trip back in time.

Tags & Taxonomy

For more than 70 years, phosphate mines were exploited close to the Wallonian city of Mons, in Brussels, Belgium. The phosphate was used, among others, in the sugar industry and to create fertilizer.

To the local population, the mines were of great importance as they provided jobs and income to many thousands of local inhabitants who worked year after year underground to delve the phosphate. They worked 13-hour days in harsh conditions and were always in danger of their lives. In that day and age, child labor was normal and the youngest were barely 12 years old. During World War II, the mines were also used by the Resistance to hide refugees and weapons.

Phosphate was first discovered in 1875 and the mining of it continued till the 1950s. During this period, hundreds of thousands of tons of this precious product was brought to the surface. When phosphate mining was stopped and the mines closed, they found a later purpose as a mushroom farm. Meanwhile, a large part of the mines had been flooded by the rising groundwater.

This water was so pure that a local brewery used it to produce beer which was then sold locally. The flooded part is now the largest reservoir of spare drinking water of the whole area. The total length of the tunnels is more than 260 kilometers! From 1995 onwards, guided tours were organized in the dry portion of the mine so people could learn how our ancestors lived in the past. During this period, the tunnels and caves were also examined by paleontologists, who then discovered remnants of prehistoric animals in the mines.

The first exploration dive

The mines of Mons are perfectly hidden in the landscape and, as such, it was no easy feat finding someone to guide me during the exploration. The flooded tunnels are many kilometers long and one should be well prepared before starting a dive like this.

Kevin Haeke, an experienced cave diver, was prepared to guide me during a dive. First of all, it was quite a job getting all the material needed and the rebreathers to the spot where we would enter the water. When all the equipment was there, we took our time to prepare and test our rebreathers.

I would make the first dive without a camera so I could concentrate on reconnoitring the area for when I would return with a camera for the photo dive. After a final check, we started the dive and I followed my guide into what was for me unfamiliar terrain. At the beginning, the visibility was bad but the further away we swam from the point of entry, the clearer it became, eventually turning into crystal clear water.

The first part of the tunnel we swam through was fairly narrow, but after the first corner to the right, the space became much larger. During the first hundred meters of our exploration, we encountered many objects used in the past during the excavation process.

Right from the start, where we entered the mine, one of our team members played out a guideline. This would enable us to always find our way back to the entrance. One of the advantages of phosphate over slate rock would be the walls having a much lighter color (yellow and orange). This light coloring gave us the impression that the visibility was also much better.

After swimming for a while, we noticed several side tunnels on the left and right, which each had side tunnels going in different directions. It quickly became apparent one had to be very careful with the guideline so as not to get lost. The total size of the labyrinth is about three kilometers long by 450 meters wide.

After almost 40 minutes of swimming, we reached an area where we could poke our heads above the surface, revealing another exit. After a short break, I was guided safely back to the entry point by my two guides.

The dive left a deep impression on me and I planned to return as soon as possible with my camera.

Paradise for an underwater photographer

It was not long before I found some good diving friends willing to join me on a dive to take pictures in the phosphate mines of Mons. Stefan Panis and Karl Van Der Auwera are regular dive buddies, and the third diver I found (Michael van Dijck) had lots of experience in cave diving. Before my second dive, I wanted to prepare myself properly and spent half a day preparing my camera and the flash units.

Our intention was to light up as much of the long tunnels as possible using remotely operated flashlights. Stefan and I would be diving with Buddy Inspiration rebreathers and the other two divers would be using open circuit. To take the pictures, we would swim towards the clearest part of the mine and take some shots there.

Michael’s assignment was to guide us safely back to the entry and not lose sight of the guideline. On this dive, I was solely focused on the photography and choosing the right angles so I would not be paying attention to the guideline; hence, Michael was my safety diver.

Several minutes after our departure, we reached the clear waters and I started to take my shots. We had agreed not to swim too close to the bottom so as not to disturb the sediment and reduce our visibility.

On this dive, I noticed the height of the main tunnels was at least six meters, and they were four meters wide. At some points, the strut bars to prevent the tunnels from collapsing were still visible.

At several spots, the iron tracks of the mining carts and locomotives were still recognizable. Again, during this dive, it became clear to me how large and extended this system was and how easy one could get lost in it. Therefore, we paid attention to where we placed our markers so as to be able to find our way back.

After a swim of about 500 meters, we decided to return and reconnoitre some of the side tunnels on the way back. These were much lower than the main tunnels and gave me the impression that some of them were dug above each other. At this spot, I took some last shots before we made our final return to the starting point.

Along the way back, we tried to get a mental image of the numerous tunnels of this underwater city. When we surfaced at the exit after more than 80 minutes, the whole team was euphoric about this beautiful dive spot. It would take many more diving hours to map this beautiful and enigmatic hidden place.■

Having dived over 400 wrecks, Vic Verlinden is an avid, pioneering wreck diver, award-winning underwater photographer and dive guide from Belgium. His work has been published in dive magazines and technical diving publications in the United States, Russia, France, Germany, Belgium, United Kingdom and the Netherlands. He is the organizer of tekDive-Europe technical dive show. See: tekdive-europe.com

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #72

Japanese wrecks of Kwajalein Atoll; Canary Islands' El Hierro; Mexico's La Paz; Croatia's Stuka bomber wreck; Wrecks of Palau liveaboard adventure; Wakatobi getaway; Belgian mines of Mons; Black water diving in Palau; Scuba Confidential: Masking the problem; Managing stress in diving; Sharks don't bite like we do; UW Photography: Contrast, lines, haptics; Corinne Chaix portfolio; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, shark tales, whale tales and much more...