Coral populations in North Atlantic under threat from climate change

According to researchers at the University of Edinburgh, changes in the winter weather conditions may affect the long-term survival of the region's corals, disrupting fragile ecosystems and marine creatures that depend on reef structures to provide shelter from predators and safe spaces to reproduce.

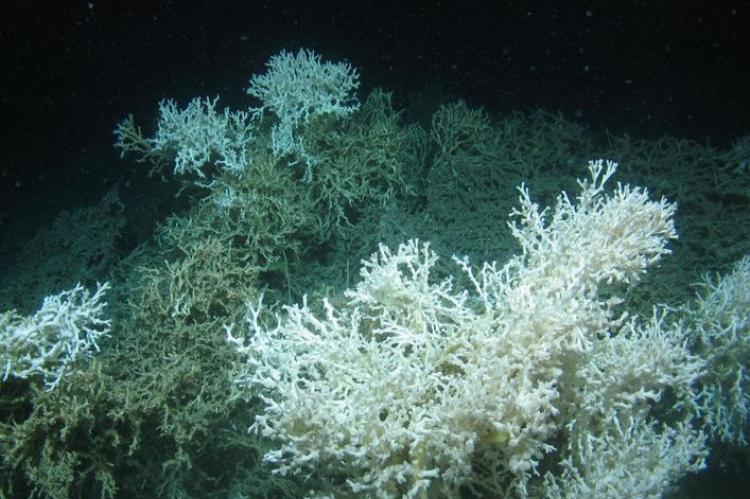

The team focussed on a cold-water coral species (Lophelia pertusa) which grows in deep waters, creating elaborate reefs that are hotspots of biodiversity. These populations are maintained by small, fragile coral larvae that drift and swim on the ocean currents, travelling hundreds of miles between reefs where they attach and begin to grow.

Computer models were used to simulate the migration of larvae across vast stretches of ocean, to enable researchers to predict the effect weather changes could have on the long-term survival of the corals in the North Atlantic.

Dr Alan Fox, of the University’s School of GeoSciences, said: “We can’t track larvae in the ocean, but what we know about their behaviour allows us to simulate their epic journeys, predicting which populations are connected and which are isolated.”

They discovered that a shift in average winter conditions in western Europe, a possible result of climate change, could threaten coral populations. Ocean currents, affected by changing wind patterns, could drive larvae away from key sites in a new network of marine areas established to help safeguard coral populations, researchers said.

In addition, the team found that Scotland’s network of Marine Protected Areas appears to be weakly connected, causing it vulnerable to the effects of climate change. A coral population on Rosemary Bank seamount, an undersea mountain off Scotland’s western coast, is key to maintaining the network.

Dr Fox said that “in less well connected coral networks, populations become isolated and cannot support each other, making survival and recovery from damage more difficult.”

Corals also thrive on the oil and gas platforms in the North Sea and west of Shetland. According to the researchers, this may help in bridging a gap in the MPA network between populations in the Atlantic and along the coast of Norway.

Professor Murray Roberts, of the University’s School of GeoSciences, said: “Scotland’s seabed plays a unique role as a stepping stone for deep-sea Atlantic species. By teaming up with researchers in Canada and the US, we will expand this work right across the Atlantic Ocean.”