Diving the Arrow

It’s an unsettled kind of morning on Chedabucto Bay of Canada’s east coast. The sun is shining—it’s really quite pleasant—but there’s a brisk wind blowing from the southwest. What that translates into here in the waters between Cape Breton Island and Nova Scotia is heavy seas. We’re pounding through four to six foot swells in a 25-foot rigid hull inflatable boat. The ride out to the dive site is turning out to be a wild, you might say bone-jarring, experience. All this for a dive that I’m still not certain I want to do at all.

Tags & Taxonomy

The other question mark: What am I going to find? When the Arrow went down on 4 February 1970, it was an environmental disaster of catastrophic proportions—one that at the time rivaled the more recent Gulf of Mexico disaster. Am I going to find a thriving artificial reef or a still leaking environmental killer?

How it happened

The weather was sunny but windy on that winter day when the Olympic Maritime ship Arrow entered Chedabucto Bay. She was hauling 108,000 barrels of Bunker C fuel oil for Imperial Oil, on her way to offload at Nova Scotia Pulp Limited. The Arrow was not what one would describe as the pride of Aristotle Onassis’ fleet. She was 20 years-old—the second oldest ship in the fleet—and the Arrow wasn’t in a great state of repair. In fact, virtually all of her navigation systems, with the exception of her compass, were out of order.

As she entered the bay the Arrow encountered heavy rain and winds gusting to 60 knots.

Slowly but surely, as the ship made its way down the bay she drifted out of the shipping lane. By the time she was way halfway, the Arrow was well out of the safe zone. At 9:30 a.m. she struck Cerberus Rock and ran herself well up onto the reef. Initially officers and crew were not overly concerned. They tried full reverse to get off. No luck. But the captain, George Anastassopoulos, felt that they still could work free at high tide. No distress signal was sent. The first step toward an environmental disaster had just been taken.

Diving the Arrow

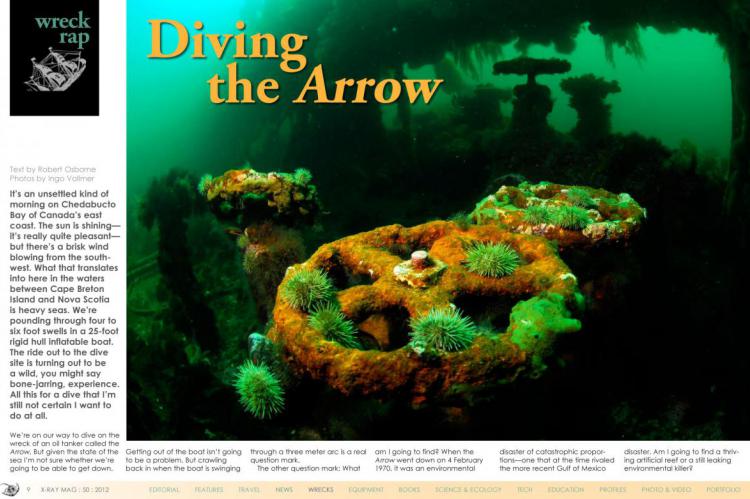

After 20 minutes of pounding through the waves we arrive at the buoy that marks the location of the wreck. My host, Ingo Vollmer, casts a skeptical eye on the water conditions. Finally, he makes a decision: “I think it’s possible.” I slide into my dry suit and gear up. My dive buddy for the day is Ingo’s wife, Anita. We roll backwards off the RHIB and swim over to the descent line. A quick check and we submerge. Right away I can tell this isn’t going to be a promising dive. It’s only 30 meters deep here and the rough water has churned up the bottom. We descend to the wreck with only two to three meters of visibility and hit the top of the superstructure at about 20 meters. I can see we’re on a wreck, but not much more.

We’re on our way to dive on the wreck of an oil tanker called the Arrow. But given the state of the sea I’m not sure whether we’re going to be able to get down. Getting out of the boat isn’t going to be a problem. But crawling back in when the boat is swinging through a three meter arc is a real question mark.

Fortunately, Anita knows this dive site like I know my neighborhood; she could find her way around blind folded. She signals me to follow. We manage to complete a circuit of the wreck—down to the rudder at 30 meters and around the hull—but all I can make out are just vague dark impressions. After 30 minutes we give up and head for the surface.

And this is where the dive gets a little tricky. The winds have picked up even more. The RHIB is bouncing up and down in a dangerous manner and there is no dive ladder. Getting back in is like something out of a rodeo. We have to catch hold of a rope and, while hanging on the side, remove our BCDs and weight belts, hand them up to the boat tender and then heave ourselves in. At the top of the arc my feet are nearly clear of the water, at the bottom I’m submerged to my neck. My arm and shoulder get severely yanked around and it takes some real work to hang on, but eventually I manage to get all my gear off and haul myself up over the side. I’m getting too old for this stuff, though I have to admit I feel vaguely like a Navy Seal when it’s all over. Ingo asks me how the dive went. When I tell him, he says: “We’ll try again tomorrow.” He fires up the engines and we head for shore.

History

Hoping tomorrow would bring a better day was something that Captain Anastassopoulos was relying on. He was certain that he could reverse his ship off the rocks. But after trying all day without success he began to realize this was more serious than he’d first thought. The weather was starting to turn really ugly. Finally, he sent out a distress call. A Canadian Fisheries vessel responded and removed most of the crew.

During the next day several attempts were made to tow the Arrow off the rocks. All attempts were unsuccessful. It was finally decided that to pull the ship off the rocks, the oil would have to be pumped out. But salvagers decided to wait until the following day—a decision that some see as the second major error in the catastrophe.

The next morning was too late. When crews arrived on site, a three mile-long oil slick had already spread out across the bay.

Overnight the Arrow had split and ....

(...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

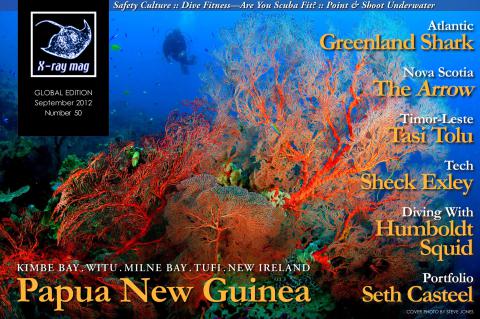

X-Ray Mag #50

Papua New Guinea: Kimbe Bay, Witu, Milne Bay, Tufi, New Ireland; The Greenland Shark; The Arrow, Nova Scotia; Timor-Leste's Tasi Tolu; Sheck Exley on Mix; Diving with Humboldt Squid; Safety Culture in Diving; Dive Fitness: Are You Scuba Fit? Point-and-Shoot Underwater Photography; Underwater Dogs by Seth Casteel. Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, turtle news, shark tales, whale tales and much more...