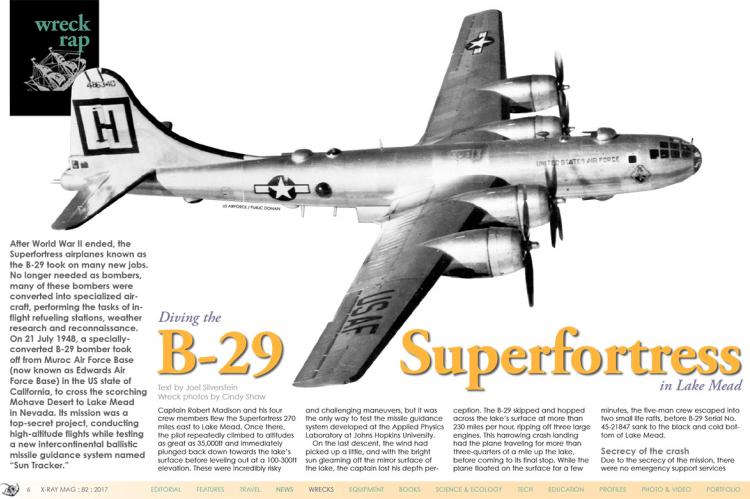

Diving the B-29 Bomber

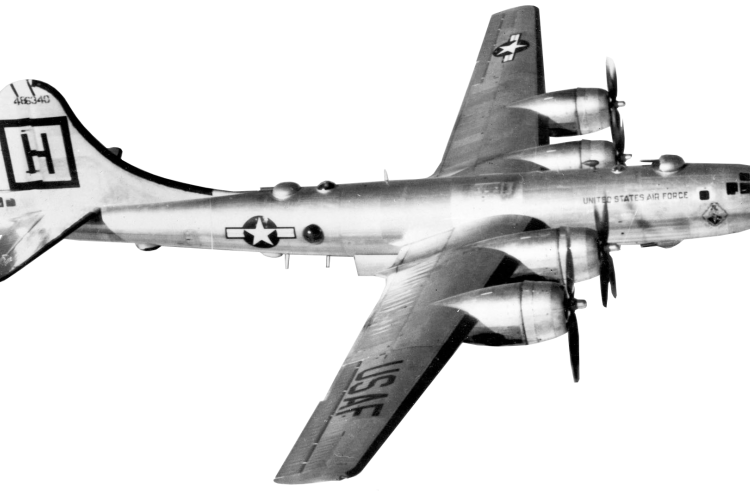

After World War II ended, the Superfortress airplanes known as the B-29 took on many new jobs. No longer needed as bombers, many of these bombers were converted into specialized aircraft, performing the tasks of in-flight refueling stations, weather research and reconnaissance. On 21 July 1948, a specially-converted B-29 bomber took off from Muroc Air Force Base (now known as Edwards Air Force Base) in the US state of California, to cross the scorching Mohave Desert to Lake Mead in Nevada. Its mission was a top-secret project, conducting high-altitude flights while testing a new intercontinental ballistic missile guidance system named “Sun Tracker.”

Tags & Taxonomy

Captain Robert Madison and his four crew members flew the Superfortress 270 miles east to Lake Mead. Once there, the pilot repeatedly climbed to altitudes as great as 35,000ft and immediately plunged back down to the lake’s surface before leveling out at a 100-300ft elevation. These were incredibly risky and challenging flights, but it was the only way to test the missile guidance system developed at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University.

But on the last descent, the wind had picked up a little, and with the bright sun gleaming off the mirror surface of the lake, the captain lost his depth perception. The B-29 skipped and hopped across the lake’s surface at more than 230 miles per hour, ripping off three large engines. This harrowing crash landing had the plane traveling for more than three-quarters of a mile up the lake, before coming to its final stop. While floating on the surface for a few minutes, the five-man crew escaped into two small life rafts, before B-29 Serial No. 45-21847 sank to the black and cold bottom of Lake Mead.

Secrecy of the crash

Due to the secrecy of the mission, there were no emergency support services available in the event of a crash. The entire crew was picked up some six hours later by National Park Service (NPS) employees. Because this was a secret mission, Captain Madison and his team were instructed to keep the mission, the crash, and the general location of the sinking secret.

For more than half a century, the B-29 bomber rested quietly, more than 260ft below the surface in a remote location of the lake. No efforts were made to recover the plane or the technology it was carrying. In 1948, the deep-sea technology did not exist for salvage dives necessary to retrieve the aircraft. As with all vessels that sink in a national park, the B-29 became a cultural asset of the United States even though they had no idea of its precise location.

Quiet discovery

During the next half century, the little town to the west, known as Las Vegas, boomed from under 30,000 people to over 600,000 residents, with more than 39 million annual visitors. Behind the glitter and glamor of Las Vegas, the lost B-29 remained on the minds of the budding technical diving community of the city. Quietly, and without much disclosure to other than a private team, diver and underwater researcher Gregg Mikolasek located the B-29 bomber using side-scan sonar equipment in 2001.

The details of the first dives on the plane have remained something of a deep secret, as well as the names of the divers who have dived it. Embroiled in litigation, the location and ultimate ownership of the B-29 bomber remained with the National Park Service, which is the steward of this historic site.

Government survey

In 2003, the National Park Service Submerged Cultural Resources (SCR) underwater archaeological team conducted an extensive dive operation on the B-29. Their activity mapped, photographed and detailed every aspect of the sunken Superfortress, which now lay in 180ft of water. This formidable task required setting out a four-point mooring system, so the dive platform barge could suspend an underwater “chandelier” to light up the site, and to manage the small ROV that was used to recover video from inside the tiny compartments of the plane.

The agency’s work produced an extensive management and educational document to aid in the conservation and preservation of this historic site. During the operations, my wreck diving colleagues, Richie Kohler and John Chatterton, produced an episode for the Discovery Channel's Deep Sea Detectives program. This B-29 is the only B-29 in existence that is underwater.

After the NPS documented the site and developed a management plan, the next step was to develop a method for the general public to visit the site. Unlike some other resources in a park, underwater sites present a host of challenges for both the park and the public. For the B-29, some of the problems included its remote location, far from any services; the depth of the water, which was beyond established recreational dive limits; and the fragile state of the plane itself.

To open the site with unrestricted access would inevitably destroy the thin fuselage and risk removal of artifacts. The development of a management process took several years with additional research dives to further evaluate the plane’s condition. Finally, in late 2006, the NPS approved a system that would allow for “Technical Guided Dives” on the B-29. But who in the southwestern region could or would take this on?

Taking on the challenge

Through our company, Scuba Training and Technology Inc. based in Lake Havasu City, Arizona, Captain Kathy Weydig and I took on the challenge. We have extensive experience with managing shipwreck dives in remote locations as well as working on protected wreck sites. For almost two decades, we have run technical diving expeditions to the wrecks of the Andrea Doria, USS Monitor and other wrecks that require safety and precision operations. With a nearly 80-page document detailing our experience and activities plan, we were awarded the first Commercial Use Authorization (CUA) to conduct guided technical dives on the bomber.

The first year had operational complexities that were not only stressful, but costly. The initial CUA limited access to no more than four single dives in a week, and 50 dives in total over six months. After the initial trial, the NPS would either extend or suspend operations for the following year.

Dive conditions

In 2007, due to the drought in the southwestern region, the B-29 was resting in approximately 165ft of water. These depths required the use of trimix to eliminate inert gas narcosis. Divers would be at a 1,100ft elevation; water temperatures on the lake bottom were in the low 50s F; and the lake had a moon-dust bottom that could easily silt up, not dissipating for days. Some other challenges included the fact that the site was 35 miles from the nearest marina and winds could reach up to 20 knots!

Diving the wreck

A typical dive consisted of a well-trained guide and two dive clients. Divers descended on the mooring line to the bottom of the lake where they met the 12,000lb mooring block. From here, divers traversed approximately 85ft along a line to the second mooring block at the stern of the B-29.

The tour followed around the port side of the fuselage, then around the port wing, examining the engines, propeller and landing gear. Next came the nose and the pilot's areas. This brought one around to the starboard side of the plane.

The starboard wing was buried in silt, so exploring this area was not necessary. But divers could continue along the starboard fuselage, examining the dome of the “Sun Tracker” on the way to the tail section, which rose over 30ft. After the tail section and tail gunners port were viewed, divers jumped back onto the guide line and back to the mooring cable to make their ascent, resulting in a total run-time of about an hour.

Economic downturn and waning interest

While the first year on the bomber was successful, the economy in 2008 took a serious downturn, and it was exceedingly difficult to get divers to travel to Las Vegas to dive this special site. Over the next few years, the B-29 rested on the lake bottom without any activity, other than some inspection dives by the NPS. As the B-29 receded into its secret location, with few seeking to dive it, so did the water level of Lake Mead. As a quagga mussel infestation quietly covered the B-29, the extreme drought pushed the water level of Lake Mead to an all-time low, dropping it another 40ft.

Re-opening the site

During the eight years since our team dived the B-29, the economy recovered. Divers were now traveling to extreme and remote sites again. But what about the B-29?

It was mid-December 2015 when a text message came from FOX10 news anchor Troy Hayden. His message: “We’re doing this, right?” With a puzzled look, I saw an email from the NPS simultaneously appear on my screen. The NPS wanted to reinstate dives on the B-29 again!

Without hesitation, I called our CUA coordinator at the NPS, and they were thrilled that we would be crazy enough to conduct dives to the site again. However, we still needed to go through the entire application process again.

In another call to Troy, he said he wanted to be the first to do a feature story on the secret B-29 bomber in Lake Mead. But now we needed a permit, so we submitted our paperwork, and we waited. Because the NPS was seeking two operators, the deadline for applications was extended. And so, the wait continued.

It was now February 2015, and we continued to wait. Then finally, towards the end of March, we were notified that we were issued the exclusive permit for conducting dives on the B-29 for 2016.

On 14 April, we met with the National Park Service and the SCR team. A permit was handed to us. Meanwhile, our boat was out in the parking lot, and we hightailed it up to our launch area far up in the north end of Lake Mead, some 70 miles from where we are.

Return to the wreck

We needed to conduct a reconnaissance dive, because Troy and his camera people were due first thing the next morning to shoot the story. However, the weather was not our friend in April; the wind was blowing, and the seas were building. Captain John Fuller and I made our way to the site. I splashed in and spent an hour getting our sub-surface mooring line re-established. Then, it was time to dive the wreck. I have not been on the B-29 since 2008. What was I going to find on the wreck? What condition was she in? What new piece of history would I uncover?

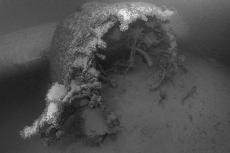

On my descent down the steel mooring cable to the twin 12,000lbs blocks, the clear blackness of the water was a familiar sight. I made my way across the 87ft traverse, when a huge shadow in the distance came into view. I exhaled a smooth “there-she-is” as the huge dark area morphed into the still magnificent tail rudder of the Overton B-29 Superfortress bomber on its final landing pad.

I had the B-29 all to myself for the next 30 minutes. This time, however, she was at a much shallower depth than ever before, 120ft from the surface. Surely, this would be an easy decompression dive, I thought.

Remembering my tour path, I hovered around the tail cone, lighting up the engraved panels with my dive light and inspecting the latest quagga mussel growth. Much of the wing fabric had torn away from the combination of the weight of the mussels and the hydraulic action of the lake.

Moving down the port side, I could clearly see the twisted metal where the fuselage cracked as the B-29 fell into a gully on the bottom. And as I swung around to the port wing, I could see over the top to the Number 1 engine, with its propeller still intact.

As I made my way around the wing tip, I saw that the aileron on the back side of the wing had new indentations where the quaggas pressed through the dope-covered fabric. As I swam around the propeller, it looked as though it was encased in a fuzzy sweater. The slick metal I had last seen on the propeller was now covered in quagga mussels.

With time running out, I headed to the cockpit to ensure that all was how I had left it years ago. Atop the fuselage was the “Sun Tracker” dome, intact, as was the starboard wing. My mind raced ahead to the next day when I was to take Troy on his dive for the news story. Blocking out shots in my head, I wondered how we could get it all done in two dives. Twenty minutes later, on the surface, the seas had turned, and three-foot rollers were splashing over our boat deck. It was time to get back to the launch ramp.

The next day, the seas had calmed a little, but were still too rough to get out to the site in the morning. We caught a break about three hours later, and made a run for the site. On board was Troy, Captain Weydig, Captain Fuller, Joe Cocozza and myself. We got Troy rigged in full-face mask gear, with underwater communications, and we hit the water. Joe, Troy and I got all the underwater images and sound recordings to make a great story.

Increased interest

The next few months were filled with divers and news media wanting to dive the famed B-29 bomber. The B-29 and our team became the press darlings of the NPS. We did television, radio and print stories with CBS, NBC, PBS and NPR. In addition to that impressive list was coverage by The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, as well as all the syndicated news wires. All told, we garnered close to 8 million views nationwide. Despite all the press and all the people wanting to dive the site, we maintained our small inventory of dives, due to the fragility of the site.

While our dive requirements were stringent, the NPS did have us relax them a little to accommodate single tank recreational divers and give access to the site to more of the general public.

We learned a lot during the first year back on the site. Mostly, we learned that divers who were not highly experienced had no business diving the B-29. The site was too fragile and too deep for the average diver, despite our having highly experienced guides and crew. The 2015 season came to an end, and we were already booking for 2016.

Troubling times

Although 2016 proved promising, it was a year wrought with problems. About a month after starting the season, the NPS temporarily suspended our CUA permit, claiming that an agency’s inspection revealed damage to the port wing aileron. This suspension caused us to cancel almost three months of diver activity with a significant financial impact.

Yet, when our permit was reinstated, it was because there was, in fact, no damage to any part of the B-29. It had been an error in the evaluation of the site by the Park Service. Now midway through the season, we were faced not only with a shorter season, but lowering lake levels, putting the B-29 at just under 105ft deep. The shallower water meant poorer visibility, and at times, more trying topside conditions. Having lost a few months of operation, we moved clients to dive tour slots later in the year, and operations resumed as normal… until, one day, our world turned upside down.

Emergency incident

We did not dive the site in July and early August, due to air and water temperatures. It was too uncomfortable for most people when the air temperature was above 110ºF. So, we pushed our trips to the end of August, with a four-day run of four divers each day.

Friday was a perfect day, the visibility was a reasonable 25ft, and the lake was relatively calm. Saturday was proving to be just as good. We had a group of divers in from Florida, a course director, an instructor and two divers with many years of experience. These guys had been diving together for a while, both in the States and abroad.

Due to a minor equipment issue, one diver did not do the first dive with his guide and partner. He opted to go in a little later with one of our guides, one-on-one.

After the first dives, all the divers were just thrilled with their visits to the B-29 and the detailed tours of the wreck site. After a surface interval, tank change and some snacks, the teams started to roll in again. Time separation between teams was about 45 minutes. As I was the last diver in the second team to submerge, I saw the third team pass me on the way down. Back on deck, I noted the time and had the divers begin putting away gear, so when the third team came up, we could be on our way without much delay.

While the divers were recollecting their dives and putting away gear, I noticed bubbles coming across the traverse line from underwater and knew the divers were making their way back to the mooring line for their ascent. A few minutes later, one of our dive guides shouted, “Diver up!” and dived into the water, followed by one of the clients.

Not more than 15ft off the bow, the divers saw it was their friend. They rolled him over and got him back on the deck. Two other divers assisted getting the victim on board, while I notified NPS that we had an emergency, needed a rescue boat and emergency medical services activated. As CPR and first aid were being rendered, I set up a triage area on the vessel and got everything in order.

Fortunately, a Ranger boat with a paramedic on board had picked up our radio call a few minutes earlier. We helped transfer the diver to the Ranger boat and off they went. Just as they left, the last dive guide surfaced. We got him on board, released the mooring and sped back to the launch ramp.

Tragic outcome

As an extreme diving expedition leader for almost three decades, I have managed more than my share of incidents. Everything from a broken foot from a dropped tank, to oxygen toxicity underwater, decompression illness, arterial gas embolisms, and more than a few airlifts. However, for this one, I did not have a good feeling about its outcome.

About 25 minutes later, we approached the dock, and it was filled with emergency personnel. Amazingly, even in this remote location, there were enough services nearby in the park that a full paramedical team was on site when the Ranger boat arrived. For the next 25 minutes, we watched as the paramedics did everything they could to revive the diver. Unfortunately, they were not successful.

Amidst the tragedy, our entire crew and passengers were required to be interviewed about the incident and equipment collected for the medical examiner. Within a few hours, it was clear that we would not be diving the B-29 anytime soon. As per park procedure, whenever there is a fatality, the CUA permit is temporarily suspended, pending an investigation.

Consequences

Following the suspension, divers who had traveled from distant places to dive the B-29 the next few days had to be called and informed. While it was disappointing, a moment of pause was in order. We hoped we would be back on the plane within a few weeks. Once we saw the investigation continuing for three weeks, we were forced to cancel the rest of our season.

The medical examiners finished their report at the end of December. They stated that the diver perished due to rapid ascent from a scuba dive with significant prior contributing medical history. We were cleared of the incident, and NPS granted us an extension on our CUA into 2017. But would it be worth going back?

Green light

Once given the green light, we re-booked divers whose tours had been canceled in 2016, and made our way back to the B-29. It was a bittersweet season, back on the bomber. But my first dive to the wreck was like it had been every time I visit her. She was a huge plane resting on the bottom of the dark lake, exposing her gleaming skin to those divers who wanted to see the rare relics that survived the sea. While I made my first dive, I paused and said a little prayer for Fred Arnold, the diver from Florida who perished, and his family—as the last thing he saw underwater was the B-29.

While Fred’s death affected us all, there have been some happier moments on the B-29 since his passing. Remember that story we did with Troy Hayden at Fox News on the first day of our new permit in 2015? That story garnered us an Emmy Award for best feature story. Another special moment happened on 25 June. My son, Jona (age 15), did his first dive on the B-29 with me. It was a special father-and-son moment, which few get to experience.

But now, as our season on the B-29 comes to a close, we hope we will be back on the B-29 in 2018. A new permit process begins soon, and we look forward to taking divers to the B-29 again next year. ■

Information about diving the B-29 can be found at: http://www.divetheb29.com/b29.

Joel Silverstein is the vice president and chief operating officer of Scuba Training and Technology Inc. / Tech Diving Limited and has been exploring shipwrecks and training technical divers since 1988. He is known for asking the hard questions as well as collaborating to develop viable solutions to complex problems.

Download the full article ⬇︎