Diving in Bodrum, Turkey

As the novel coronavirus spread around the world, dive operators in all corners of the globe had to adjust to a new normal. One dive operator, Farfat Jah, made unique changes. Here, he takes an honest look at a destination forced upon him by the global pandemic.

The global pandemic affected the travel industry like no other. As it spread across the globe, our world started to implode. One by one, every dive destination that we offered closed to our customers: Micronesia, Asia, Melanesia, the Middle East and finally Africa and the Atlantic island of St Helena shut their borders. We got all of our clients home before the airlines ceased to fly, and then the email and phone went quiet.

“This will be over in a couple of months,” we thought. “Europe will beat this like China did, and it will be business as usual.” But two months became four, and four became six. We simply sat out the curfews and planned and planned and planned the future—and that was all we could do. We, like so many other dive tour operators, were looking down the wrong end of a financial barrel.

As the pandemic progressed, one shining light seemed to appear. Turkey had been subjected to the worst of the virus and it had ripped through its people of all ages, but through a no-nonsense lockdown, the country had stopped it in its tracks.

As society opened up, a second wave looked imminent. Yet, dependent upon tourism, the government was caught between a rock and a hard place. The Turkish authorities and their scientists then came up with an intelligent way of hosting tourists while protecting them and their own Turkish citizens. I will not go into the details here, but masks, disinfectant, the closing of discos and constant temperature checks were part of the employed solution.

We were over the moon as anyone could (and still can) visit Turkey, but the big question was: could we persuade our “cultural clients” to visit Turkey, and was the diving good enough? This diving was the lump-in-my-throat moment. In 1994, I had completed a very rigorous divemaster course in Fethiye. While I enjoyed it, I remember lots of rocks and seeing just a few groupers. Was the diving interesting enough? It was time to find out.

So, with rather low expectations, my wife and I flew to Istanbul and hired a car. I had been unsure of flying domestically but my worries had been unfounded. Our Turkish Airlines Dreamliner to Istanbul was clean and quiet, and all the middle seats were left empty. Food was served in bags, we all wore masks, and everything was disinfected. We were just so excited to be flying after seven months locked up in a tiny house that we would have stood the whole way if we had to.

Kenan Dogan, Bodrum’s diving pioneer

Our next problem was who to dive with. There were plenty of operators in Turkey, but we were completely out of touch. A decade ago, I had met a mad Turk and his wife on a motorbike in Africa. He now ran an adventure tourism company called Ibex Adventure Club. We turned to Deniz and Elif for help. They invited us to stay in their house and pondered over our problem. And between guiding clients on tailor-made tours, they sat with us on their balcony, overlooking Bodrum and found a solution.

“You better dive with my mate Kenan Dogan,” said Deniz. This name sounded familiar, but I had met an awful lot of people in the global dive industry, so I put it out of my mind. We called Kenan.

“Can we dive with you?” I asked. “I am a dive tour operator, but I hear you are pretty full.”

“Come, come!” he shouted down the phone. “I’ll give you a discount, but just come. Bitez Port, 09:30, tomorrow.”

And with that, the phone clicked, and he was gone. Kenan sounded like a fairly gruff character, but he was squeezing us onto his dive boat during a global pandemic, so who was I to complain?

MV Vertigo

The next morning, we turned up early and looked for the Aquapro dive vessel. We found it moored at a jetty and loaded our kit onto the boat. Unlike most Turkish dive boats, this was not a wooden taka (caique) with a marinized Ford truck engine. Rather, it was a purpose-built metal-hulled dive platform with twin Volvo Penta diesel engines.

The MV Vertigo reminded me very much of a slightly small Red Sea liveaboard. The dive deck was run by a steely, blue-eyed man called Can (pronounced “Jzun” in Turkish). A veteran security officer, he was a CMAS instructor and a good organizer. He conducted a few basic checks, we had our temperatures taken, and then we went upstairs to sit down. Soon enough, a tall, wizened man with a thick, black beard and sunglasses appeared.

“Farhat! I remember you!” he shouted at me. We had indeed met at the BOOT Show in Düsseldorf, and his memory had not failed him. Kenan Dogan had arrived. He walked straight up to the helm, turned on the engines and watched them warm up. As soon as he was satisfied with his gauges, he tooted the horn three times as a signal to his crew and any latecomers, and we slowly chugged out of Bitez Bay.

Like every Turkish man, Kenan had been conscripted into the Turkish Armed Forces at the age of 19. He was selected for dive training and spent his two years as a Turkish naval diver. As soon as he was discharged from the navy, he became a commercial diver and then went on to start his own dive centre. At the age of 56, he had been diving in the Bodrum area for the last 30 years, and as he was to prove, there was very little he did not know. Since 2007, Kenan and his friends had been instrumental in sinking three wrecks in the area.

Big Reef

Forty-five minutes after leaving Bitez Marina, Can came upstairs and told us it was time to dive. We pulled on our scuba sets and jumped into the water. I descended on what looked like a pile of rocks. This, I thought, was going to set the tone for the rest of the day. But upon closer inspection, I realised that we had actually landed on an underwater pinnacle. Can was getting the group together, so I looked down and around. This pinnacle was massive; it rose off the floor of the Aegean Sea.

Can signalled that all was well and that we should head off and down. We were diving in two-buddy teams. The second was made up of a young lady called Akça, who was doing her CMAS two-star certificate, and a Welshman called Andy. Andy was a former Royal Naval electronics technician and a man of few words. He was also clearly extremely experienced and demonstrated exemplary buoyancy.

Can took us slowly along the reef, descending gently from one cluster of rocks to another. At each cluster, there was a burst of life. My Inon strobe lit up the sponges under every rock. We swam slowly deeper and deeper, and then Can broke off to play with a school of barracuda, swimming lazily underneath them. They were not as large as the barracuda that you find off Papua New Guinea, but they were definitely barracuda, and they were bunched up into a circling mass.

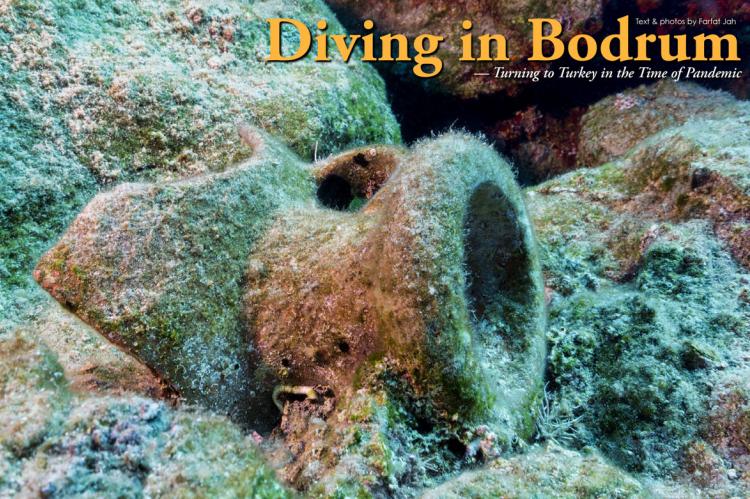

We bottomed out at around 32m. We were now well off the wall on the sandy bottom. Can was poking around some enormous boulders. He called me over. He had found nudibranchs, gobies and anthias. My flash unit fired and lit up the multitude of sponges and a small fish. It never occurred to me that the Mediterranean could be so colourful. In my youth, I had heard about the Turkish sponge divers who had discovered ancient shipwreck after ancient shipwreck, but I did not think there were any sponges left.

My computer started to beep. I had been down a while. I checked my SPG, which read way too much air. I banged it, and the gauge dropped a few bar. “I must remember to grease that spigot O-ring,” I thought, making a mental note.

My computer would not let up, and not wishing to turn my first dive into a decompression dive, I thought I should perhaps wend my way slowly upwards. We regained the wall, and then swam along it at around 18m, meeting the other divers from the boat. They had only been at 18m, but they clearly looked very happy. At this depth, schools of bream were swirling around us and even more smaller fish darted in and out of the rock face. By the time I reached 50 bar, we had circumnavigated the reef. I did my now mandatory safety stop under the Vertigo and climbed back aboard. If this dive was representative of what was to come, Turkish diving definitely had something worth visiting.

Surface interval

We motored to a quiet bay for our surface interval. Here, a couple of people tried out scuba diving. They were mentored one-on-one by the highly professional team. We simply sat on the sundeck having Covid-friendly sandwiches and tea. Andy told me a few stories about his naval service in the Falklands War that turned my hair even grayer. He chuckled as he remembered his past. “You try not to think about it really,” he smiled benignly, and we chatted about dive training. He wanted to be an instructor.

Kenan pulled out a backgammon board and flagged down a passing boat. The pleasure craft was skippered by his friend, who responded by turning into the bay, mooring up and coming aboard. Three rather fast and very furious games of backgammon ensued. When the try divers had finished, the snorkelers had tired and we had finished our sandwiches, it was time for our second dive.

Barracuda Bay

Barracuda Bay was a steep wall that ended at 33m with a series of caves. Can and Akça wandered off while I took photos. The grooves cutting into the volcanic rock made for some dramatic scenery, and the usual fish suspects were out and about. At the end of the dive, we were so taken by what we had seen that we wanted to do more.

“Can we dive a second day?” I asked Kenan. Kenan could see that we were seriously interested.

“You like it here!” he exclaimed.

“It is certainly interesting,” I was non-committal.

“Tomorrow, we will dive the Pinar 1; my friends and I sank it,” Kenan said enigmatically. And with that, we disembarked and went back to Deniz and Elif.

TCG Pinar 1

The Pinar 1 was laid down in Germany in 1938. She was then sold to the Turkish Naval Forces Command and entered service as a fleet tender. She would supply water to the destroyers and frigates. As the world’s navies modernised, Turkey’s fleet stayed the same. Her older warships did not have the ability to desalinate, and therefore a fleet water tender was as essential as an ammunition carrier.

It was only in 2007 that the need for a Pinar 1 diminished. The Turkish Navy agreed to donate her to the Turkish scuba diving community. She was stripped of military and recyclable materials, cleaned and handed over to the Bodrum Underwater Association. The Turkish Naval Forces Command towed her, free of charge, to Bodrum. There, the Turkish divers set about making her safe for diving and conducted a final, very deep clean.

In 2007, she was sunk in a spot agreed upon by the Divers Association, the Turkish Coast Guard and local government. The Bodrum Divers sited the vessel and pumped her full of water. As she started to sink, Kenan was the last man off her decks, diving into a waiting dingy—all of which can now be seen on YouTube! This was to be our wreck of the day.

Diving the wreck

Can took us down a slope of rocks, until a shape emerged out of the gloom. This was the stern superstructure of the Pinar 1. The vessel was lying bow down but upright on the sand. I circled the stern at 15m, taking a few photos, staying well off the bottom. Can signalled us to follow. I stayed at 15m, trying to take in the whole wreck in the 30m visibility. There was sea grass and sand all around the Pinar 1. I looked down and a moray swam freely between the long blades of seagrass. Schools of fish descended down off the deck and went towards the sand.

Can signalled wildly, and I looked into the blue. Some rather large stingrays rose off the bottom and swirled out in front of the bow. I could not take a photo of them, as they were beyond the reach of my lens. By now, we were at the bow, and I could take it no longer. I dropped to the floor in front of the bow. I hovered above the sand at 36m and shot the Pinar 1’s bow with my wife, Francisca, swimming beside her.

We closed in on the bow and saw rabbitfish hanging around, where the bow met the sand at 32m. The view of the side of the freighter and the sun shining down on us through 30m of blue water was serene. I snapped off a few more shots of the hull, because ships, rivets and holes interest me. They are always covered with life.

The Pinar 1 was a magnet for fishes. As with most of my Turkish dives, my dive computer started to complain. While Aquapro Dive Centre welcomes technical and rebreather divers, there was a standing request for no-decompression-stop diving, unless pre-arranged. So, with one minute remaining, I ascended to the deck and mast of the Pinar 1. Here, my Aladin dive computer relented, and I levelled off to explore the superstructure and railing.

Lionfish had arrived in the Aegean, and I found them around the hatches. While they may be destructive, they make for great photographic subjects. Francisca pointed out loads of nudibranchs on the railing, and after a deck swim-though, it was time for our safety stop and eventual ascent.

“I am blown away by the marine life,” I said to Jody Dogan, Kenan’s wife and the organiser of all activities on the MV Vertigo.

“There are eight different types of nudibranch that we see on a regular basis. This is an excellent area for macro photography,” she confirmed.

“It’s pretty good for wide-angle as well!” I retorted, thinking of the Pinar 1.

“Oh, we have more wrecks. Do you want to see the plane next?” she asked. “It is all a bit hard, you see. We have 30 dive sites, which are great, and not everyone wants to wreck dive.”

We did more dives in the area, on reefs with schools of grouper and rock faces, and on a dramatic broken-up Dakota DC3 aircraft (another military gift). Andy accompanied us for all of our dive days and served as a solid, reliable buddy for our now three-diver team. Can guided all but one of our dives, forgiving me for my trespasses.

In all our days, we did not manage to dive Barracuda Point, the Coast Guard Cutter wreck or half of Kenan’s walls. But on our last dive, Kenan strapped on his twin set, forward-rolled into the water and took us down a reef. It was packed with grouper hunting smaller fish, colourful sponges, octopuses and stunning underwater scenery. The visibility was around 50m, and it was a wonderful end to our day. Andy and I squeezed an hour out of my tank, and we ascended to our usual spot on the flying bridge next to Kenan.

“Your mind is like mine,” Kenan said. “It’s full of projects.”

“Well, Turkey is my project now,” I replied.

“I have another project,” he said quietly. “A new wreck—a big one, maybe,” he added, winking at me. “You will have to come back.”

I suppose we will just have to. ■

Five days of scuba diving and seven nights’ bed-and-breakfast accommodation, including airport transfer fees, at the Marina’da Hotel costs GB£520 (~EU€579/US$679) per person sharing, in shoulder season. Peak season, which is July through August, adds another £95 (~€106/$124). Fascinating tailor-made day trips for two people to 2,000-year-old Leleges tombs costs from £95 (~€106/$124) a head. Entry to Bodrum Castle is £6 (~€7/$9). A guide to show you the underwater museum and to explain the history of Bodrum’s underwater heritage starts at £60 (~€67/$78) a day. The African and Oriental Travel Company specialises in tailor-made Turkish Adventure tours, which lets you take in as much as you want, from the Hittites to the Urartians, from the mountains of Van to the Aegean Sea. For more information, go to: orientafricatravel.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎