Diving into a Squid Orgy

My first experience diving with mating squid was in September of 2000 during a rare late summer event off La Jolla Shores of San Diego in the U.S. state of California. To date, it still ranks as one of my all time favorite dives.

Tags & Taxonomy

Midway through the dive, something big enough to spin me around, hit me from behind and scared me silly. I don’t know if the culprit was a sea lion, shark, bat ray or something otherworldly, and perhaps it is simply better not to know, but my adrenaline was pumping on overdrive for the remainder of that dive. While I do not have pictures from that epic night, I was lucky enough to photograph another squid orgy this past December.

About squids

Common market squid (Loligo opalescens) live in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, ranging from Alaska down to Baja California, Mexico. They migrate in gigantic schools and have a lifespan of only 12-14 months. These creatures grow quickly and procreate at about one year of age. Market squid reproduce in a continuous spawning activity that can last for weeks or even months. Commonly called squid runs, these spawning events typically occur after dark, on muddy or sandy bottoms above submarine canyons. During heavy squid runs the mating activity may even continue through the daylight hours.

Southern California squid runs typically happen during the colder winter months but if conditions are right, they can occur in late summer or fall. On those years when the squid migrate up from their deep-water homes to mate at depths shallow enough for recreational diving, this nighttime activity should not be missed. Being engulfed in the mating frenzy can be an awe-inspiring experience. The squid tend to gravitate to dive lights and swarm from every direction, often making it difficult to see more than a few feet. Add in the occasional sea lion, bat ray or shark and you can quickly go into sensory overload and forget about your depth, air supply and dive buddy. Luckily, turning off or shielding the light occasionally will allow you to catch your breath, disperse the teeming squid and collect your bearings.

Squid are members of the mollusk family known as cephalopods and their relatives include octopus, cuttlefish and chambered nautilus. Common market squid are 12 inches long, iridescent white in color and like other members of their family, capable of changing color in reaction to their environment.

When a male grasps onto a female during mating, it’s arms and tentacles change from white to a deep reddish-brown. This may be a sign of excitement or perhaps a warning for other males to stay away. However, even with the warning, it is not uncommon to see several males attached to a single female, each attempting to mate with her.

After mating, female squid deposit a single, 6-8 inch egg casing containing 200-300 eggs in the sandy bottom and fertilize the eggs with sperm packets placed in their mantle cavity by the male during mating. Millions of mating squid produce immense numbers of egg casings, which create enormous egg beds that can cover acres of sea floor. Females are thought to be able to produce 20-30 egg casings before they die in this terminal breeding process.

As the squid eggs mature and develop, the egg casings start to yellow and turn brown. In 3-5 weeks, depending on the water temperature, the eggs produce hatchlings that look like tiny adults. Paralarvae, as the new hatchlings are called, are dispersed by ocean currents to start their brief life cycle anew.

Market squid are also commonly known as Calamari and frequently appear as a fried appetizer on restaurant menus. They are a good source of protein, riboflavin, selenium and B12 and in 2010; over 250 million pounds of market squid were caught off California’s coast, representing the bulk of the world’s harvest. In the wild, market squid are a vital food source for a large assortment of marine mammals, birds and fish.

Dances with squid

Photographing within the thick soup of mating squid is challenging indeed. The constantly changing scene dancing in front of your lights makes it very difficult to compose properly, and it seems that the longer you wait for a shot, the more the squid congregate and obscure the front of your lens.

In order to capture the action without the squid blocking out the entire landscape, it is necessary to point your lights away from the desired backdrop and then bring them back again once the chaos has cleared. It becomes a game of moving the lights in and out to control the ebb and flow of the squid, in hopes of encapsulating a manageable number of subjects in the frame.

A daytime dive during a squid run reveals expansive egg beds, now devoid of the thousands of squid in the water column, along with throngs of scavengers feasting on the dead and dying squid. Angel sharks, bat rays, sheep crabs, spiny lobster and countless other critters stuff themselves on the casualties from the previous nights orgy.

It is absolutely fascinating to watch the circle of life in action and observe how Mother Nature uses the demise of one generation to provide for so many others. If you have the opportunity to witness a squid run in person, I highly recommend the experience. Bring your sense of adventure and prepare to be amazed. ■

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

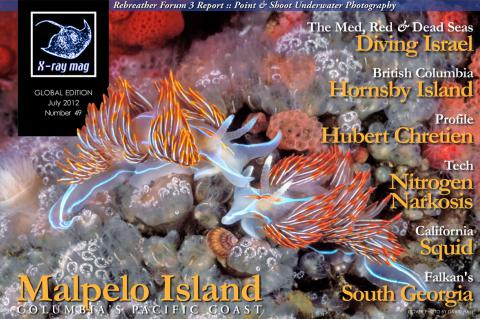

X-Ray Mag #49

Malpelo Island: Columbia's Pacific coast; Israel: Journey beyond the three seas; Hornby Island: British Columbia getaway; Hubert Chretien interview; No need to get narked, by Mark Powell; Squid orgy in Southern California; Falkland's South Georgia Island; Point-and-shoot underwater photography; Resande Man wreck; SS Dago wreck; Rebreather Forum 3 report; Rebreather training technology; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, turtle news, shark tales, whale tales and much more...

.