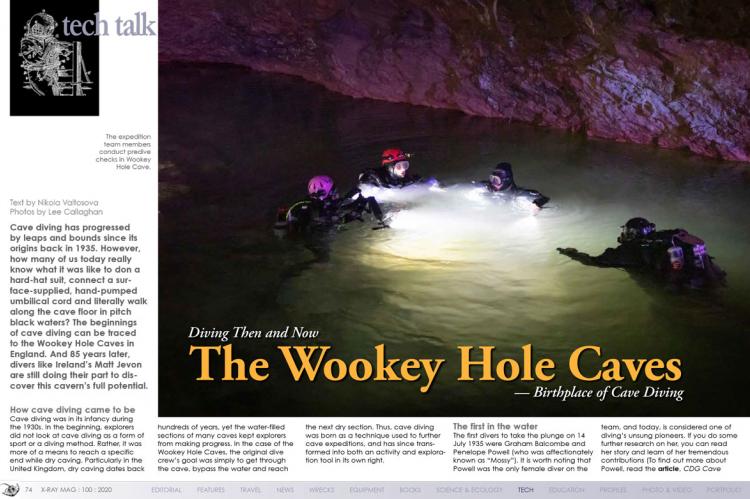

Diving Then and Now: The Wookey Hole Caves—Birthplace of Cave Diving

Cave diving has progressed by leaps and bounds since its origins back in 1935. However, how many of us today really know what it was like to don a hard-hat suit, connect a surface-supplied, hand-pumped umbilical cord and literally walk along the cave floor in pitch black waters? The beginnings of cave diving can be traced to the Wookey Hole Caves in England. And 85 years later, divers like Ireland’s Matt Jevon are still doing their part to discover this cavern’s full potential.

Penelope Powell and Graham Balcombe kitted up in Wookey Hole Cave for the first ever cave dive in 1935. Historical photo courtesy of Mendip Cave Registry and Archive Cave Diving Group.

Tags & Taxonomy

Cave diving was in its infancy during the 1930s. In the beginning, explorers did not look at cave diving as a form of sport or a diving method. Rather, it was more of a means to reach a specific end while dry caving. Particularly in the United Kingdom, dry caving dates back hundreds of years, yet the water-filled sections of many caves kept explorers from making progress. In the case of the Wookey Hole Caves, the original dive crew’s goal was simply to get through the cave, bypass the water and reach the next dry section. Thus, cave diving was born as a technique used to further cave expeditions, and has since transformed into both an activity and exploration tool in its own right.

The first in the water

The first divers to take the plunge on 14 July 1935 were Graham Balcombe and Penelope Powell (who was affectionately known as “Mossy”). It is worth noting that Powell was the only female diver on the team, and today, is considered one of diving’s unsung pioneers. If you do some further research on her, you can read her story and learn of her tremendous contributions (To find out more about Powell, read the article, "CDG Cave Exploration—Beginnings," or the book, The Log of the Wookey Hole Exploration Expedition: 1935). Unfortunately, she has been left out of several surface-level records, including the Wookey Hole Caves Wikipedia page (which states that fellow crew member Jack Sheppard, not Powell, made the first dive with Balcombe).

Powell and Balcombe’s first dive had them wearing the standard diving equipment at the time, which included brass helmets, chest plates, canvas suits and lead boots. They had to walk on their hands and knees along the cave floor in near-zero visibility, dragging their breathing hoses and lifelines behind them as the unsettled silt flew all around them. Luckily, the details about the equipment they wore was well documented and we have a fair understanding of what their dives likely looked like. It is interesting to note that the suits worn back then were made for male navy divers and Powell’s did not fit her as it should. To fix the problem, tape was used in various places to ensure her suit was properly sealed.

With the goal of further exploring the Wookey Hole Caves in mind, the divers set up a base in the Third Chamber and eventually made their way past the previously discovered Fourth Chamber to the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Chambers. They were unable to go any farther as their base-fed air lines and weighted equipment restricted them from traveling more than 61m.

Fast forward to today

Cave diving originated that mid-summer day with Powell and Balcombe. Since then, thousands of tourists—and very few divers—have traveled to Wookey Hole in hopes of discovering more than their predecessors and pushing the boundaries of technical cave diving. One such diver is Matt Jevon, an English-born Irish resident, and open and closed circuit technical and cave instructor. He has experience with both back and side-mounts and champions the CCR Liberty Sidemount.

Jevon had the opportunity to dive Wookey Hole Caves in 2019, working hand-in-hand with extreme painter, Philip Gray. Even though he began his career as an Irish Navy Diver, Gray is not your typical technical diver. His passion and love for adventure is reflected in his artwork, going to extraordinary heights and depths to achieve his artistic ambitions (see philipgray.com).

The goal of Jevon's and Gray’s dive was to enter into the same area as Powell and Balcombe and create two underwater oil paintings to commemorate the amazing feat accomplished there. In Jevon’s words, “The paintings were meant to celebrate the anniversary of the world’s first cave dive.” Gray’s work has now gone on to be featured as a permanent installment in the Wookey Hole Cave Diving Museum, which is dedicated to the monumental 1935 dive and the evolution of cave diving (see the project’s YouTube video).

Times have changed

Now, as you can imagine, the experiences of Jevon and his team versus those nearly 100 years prior differ in many ways. First, there is the gear. Even though their project was meant to commemorate the original Wookey Hole cave dives, Jevon did not wear weighted boots or a brass helmet. Instead, he ran a rebreather, and each team member’s equipment included a main light, navigational marker kit, helmet, open circuit gas, two computers, a compass and much more.

Visibility is another factor that differentiates the two dives. Powell and Balcombe were forced to work in a near-zero-visibility environment, literally kicking up silt with every step they took. Jevon and his crew, on the other hand, did everything in their power to keep the silt on the cave floor as Gray needed to see as much of the caves as he could to paint. Additionally, each diver’s main light and mandatory two back-up lights (plus the video/photography lights) allowed for a completely different scene of the cave’s chambers than what the 1935 divers likely experienced.

Jevon went on to describe the pre-dive work that went into their project. He said, “We visited the site and were privileged to be granted access to the Library of the UK Cave Diving Group to do our research.” After spending time at the library, learning more about the Wookey Hole cave dives of the 30s, Jevon and his crew took a day to both survey the cave and set up the dives that would take place over the course of the next four days.

There were, however, a number of complications they first needed to overcome. In Jevon’s words, “The main challenges were establishing a painting base over the silt. Our solution was to lay down a tarpaulin with weights, which we could then use to set up the easel. We also made sure the exit line could be easily maintained by all divers, and paid extra attention to lighting and filming within the limited space.” Once everything was in place, the actual painting sessions could begin.

With planning taking up the first day, the second day was spent in the water painting. The crew then moved the painting site and the process was continued for Gray’s second piece. With the work finished, the final day was dedicated to cleanup, where everyone did their best to leave the caves as they found them. In contrast, Powell and Balcombe did not even attempt donning their gear in the caves until they had performed a practice run in the Minories pond, which sits in the hills above Wookey Hole.

"Safety first"—past and present

There is, however, one key aspect of both dives that remained the same: safety. The original expedition invented the standard for cave diving safety at the time. They focused on open-water training, kit testing, and learned to manage as they went. Other measures included training held at the pools of Priddy Mineries, which were used as a “base camp,” and the implementation of scrupulous log keeping, good lighting and line laying, to mention a few.

Today, cave divers follow the Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival, developed by Sheck Exley and based on analysis following a high occurrence of cave diver fatalities in the 1960s and ‘70s. Being meticulous about keeping a continuous line to exit, ensuring backup equipment, gas management and reserves, safe navigation and teamwork are some of the safety points. In turn, Jevon can attest to how seriously they took safety, “In the briefings, we placed a lot of emphasis on ‘what-ifs’ over and above accepted cave diving practices. The cave is not too small but very silty. So ‘lost line, lost diver‘ procedures were very much at the forefront.”

Of course, safety also played a factor once in the water. Jevon and his team carefully calculated their run times based on safety reserves, with the safety divers ensuring these time limits were kept. Jevon explained, “We planned on one-sixteenth gas reserves for bailout and exit, whereas normal practice would have been one-third. We regarded Philip as a diver until he began painting. It was then that all his dive equipment functions were monitored by a safety diver, and it was the safety divers who called to end the session whether or not the painting was finished.”

When speaking of their gear, Jevon went on to say, “We actually omitted main reels and jump spools (not safety spools) as there would be no circumstance when they would be needed on the dives. Extra gas was the main change that we either carried or staged in additional cylinders.” As the team was running CCRs, the extra gas Jevon spoke of was in terms of the amount of bailout they would normally carry.

Recognizing those who paved the way

So much has changed since the prewar cave expeditions of Powell, Balcombe and their team. Equipment, underwater conditions, visibility and common procedures are a few to note. Even the very purpose of cave diving as a technique has evolved from a means of furthering dry-cave expeditions into the exploration and pleasure diving of fully flooded caves.

Yet, these early divers were the first to do anything like this, and from that time on, a snowball effect of new discoveries and revelations had begun. It is thanks to their pioneering efforts, dedication and passion that Jevon (or any of us, for that matter) are even able to do what we love. Not only was cave diving born that day on 14 July 1935, but the everyday practices we use as divers, such as the team approach, use of guidelines and drive to push the boundaries of diving, were put in place by the original Wookey Hole cave divers. We owe so much to them, and the least we can do is learn about those who have dived before us. Just as Jevon said, “Researching and understanding the history of where and how you’re diving is paramount.” We stand on the shoulders of giants—an expression loosely attributed to Isaac Newton (1675), and possibly even earlier to Bernard of Chartres (12th century). ■

Nikola Valtosova is a dive and travel writer, and project manager based in Prague.

Download the full article ⬇︎