Fluoro Diving and Photography

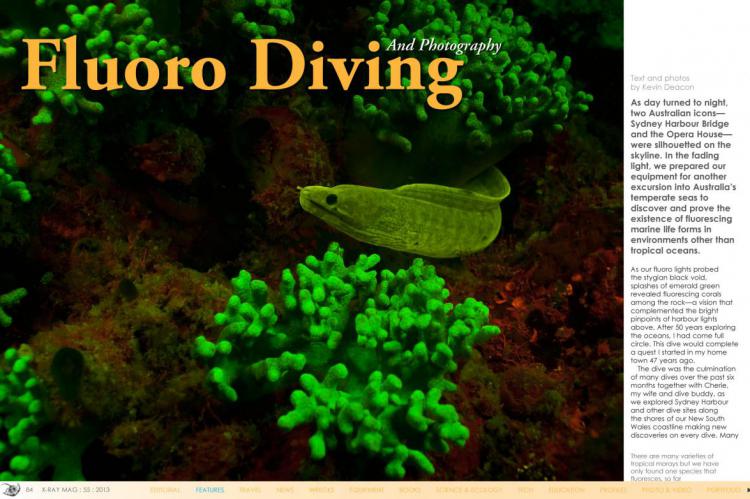

As day turned to night, two Australian icons— Sydney Harbour Bridge and the Opera House— were silhouetted on the skyline. In the fading light, we prepared our equipment for another excursion into Australia’s temperate seas to discover and prove the existence of fluorescing marine life forms in environments other than tropical oceans.

Tags & Taxonomy

The dive was the culmination of many dives over the past six months together with Cherie, my wife and dive buddy, as we explored Sydney Harbour and other dive sites along the shores of our New South Wales coastline making new discoveries on every dive. Many are world first, revealing fluorescent behaviour in species never before seen, or captured, fluorescing.

I have been fascinated with the concept of fluorescence in corals since 1966 when I first gazed upon a beautiful portfolio of fluorescent coral images in a coffee table book by Dr Rene Catala, director of the Noumea Aquarium in New Caledonia, the man who revealed fluorescent coral to the world via his specimens in aquarium tanks bathed in Ultra Violet light.

Inspired by this, I waterproofed a 12-volt UV Fluoro light powered by a limited length of cable attached to a car battery on the surface. Descending to shallow depths in Sydney Harbour, I managed to reveal fluorescence in our local temperate species of coral but the light emission was weak so it was all rather uninspiring.

That was in 1966, and as an 18 year old just starting out in underwater photography, there was a wealth of other subject matter that would attract my attention over the next 47 years. But the fascination of fluorescence and the potential for new discoveries never really left my mind, especially as it seemed by the 21st century that new discoveries underwater seemed elusive.

For a brief moment in recent years florescence in corals was once again revealed to the world in a spectacular portfolio by famed National Geographic photographer David Doubilet. But once again, this was a limited exposure, as corals were collected randomly and brought to a UV light source at a jetty so they could be photographed on site underwater. The images were excellent and once again, inspiring, but the process had not made a major leap in four decades.

New technology

Imagine if we could be free of such limitations and take the light to the animals, free to roam the seven seas and reveal all the fluorescent life forms that I was certain must exist. This would require a whole new technology, and fortunately, it was ultimately developed by Dr Charles Mazel of Nightsea.

A number of underwater photographers had already embraced the technology and begun capturing a few amazing images of fluorescing marine animals in tropical seas. It was my goal to pursue and capture even more tropical species fluorescing, but more importantly, to be the first to capture and prove the existence of such species in our cold temperate Australian seas south of the Great Barrier Reef.

Temperate water

As total darkness fell on the dive site, Fly Point at Nelson Bay Port Stephens, Cherie and I descended to the seafloor using white light to find our way. Once we were settled, we switched to the Blue wavelength created by Nightsea Excitation filters and flipped our yellow barrier filters over our dive masks. Now everything went black, as only subjects that fluoresced would be seen, so it required good buoyancy control and the use of our probes to feel our away around the dive site.

We scanned the darkness with our lights, and ahead, a carpet of fairy lights was revealed, as hundreds of tiny ascidians, sea squirts, fluoresced like Chinese lanterns. This was a good start, but I was hoping for something more exciting than sea squirts.

Hovering amongst the fairy lights, our eyes caught a sudden movement, slithering through the darkness—a moray eel fluoresced in bright yellow-green. Then, here and there on the sand, goatfish hunted for food, their tentacles glowing bright, their bodies and fins displaying alternating degrees of fluorescence, as if they had a dimmer switch controlling the intensity. Who would have imaged fish could do that?

Elsewhere on the sand, tiny emerald jewels roamed. On close inspection, these were bristle worms also known as fire worms due to their nasty sting. Why do they fluoresce? Are they communicating, “Don’t touch”?

Floating along in a gentle current, we were treated to multiple examples of tube anemones displaying their range of fluorescent colours, each one reminded me of a miniature display of fireworks, as their tentacles flowed in the current.

Sponges covered every rock, but we could barely see them in the darkness. Much of the marine life carpeting the seafloor did not fluoresce, but incredibly, just one sponge glowed in the darkness. On closer inspection, I found it was spawning, and the spawn was florescent. What would be the purpose of that? So many questions like this will keep marine science busy for decades.

Then out of darkness emerged the largest nudibranch I have ever seen in temperate seas, a Major Armina—at 90 centimetres, it is a giant among nudibranchs. They are rarely seen, as they only emerge from under the sand to hunt and feed on sea pens and soft corals.

This specimen was glowing powerfully in a vivid display of fluorescing stripes, so powerful in fact it was lighting the sand around it as it hunted. Trailing close behind, a second Major Armina ....

(...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

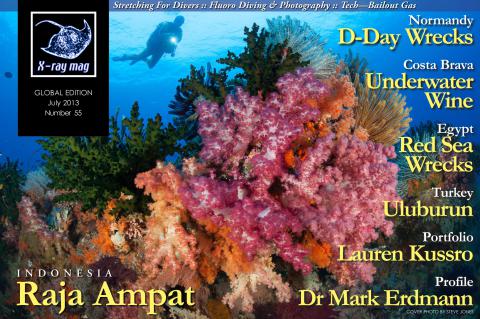

X-Ray Mag #55

Indonesia's Raja Ampat; D-Day wrecks of Normandy; Costa Brava's underwater wine; Egypt's Red Sea wrecks; Turkey's Uluburun; Dr Mark Erdman profile; Tech: Bailout gas; Stretching for divers; Fluoro diving and photography; Lauren Kussro portfolio; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, turtle news, shark tales, whale tales and much more...