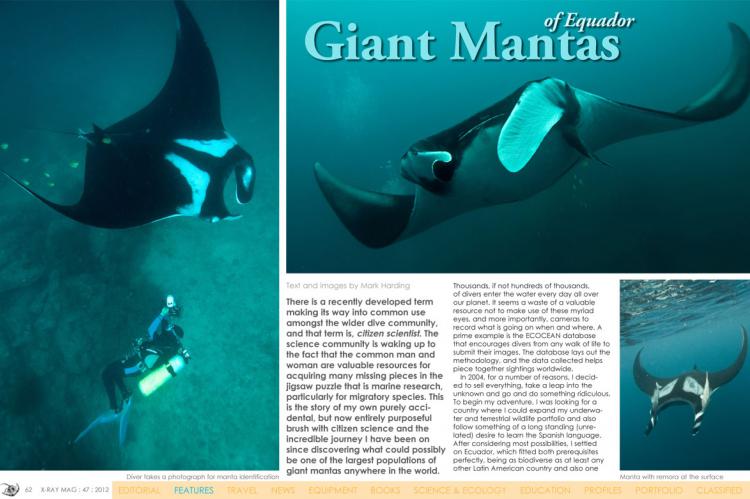

Giant Mantas of Equador

here is a recently developed term making its way into common use amongst the wider dive community, and that term is, citizen scientist. The science community is waking up to the fact that the common man and woman are valuable resources for acquiring many missing pieces in the jigsaw puzzle that is marine research, particularly for migratory species.

This is the story of my own purely accidental, but now entirely purposeful brush with citizen science and the incredible journey I have been on since discovering what could possibly be one of the largest populations of giant mantas anywhere in the world.

Thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of divers enter the water every day all over our planet. It seems a waste of a valuable resource not to make use of these myriad eyes, and more importantly, cameras to record what is going on when and where. A prime example is the ECOCEAN database that encourages divers from any walk of life to submit their images. The database lays out the methodology, and the data collected helps piece together sightings worldwide.

In 2004, for a number of reasons, I decided to sell everything, take a leap into the unknown and go and do something ridiculous. To begin my adventure, I was looking for a country where I could expand my underwater and terrestrial wildlife portfolio and also follow something of a long standing (unrelated) desire to learn the Spanish language.

After considering most possibilities, I settled on Ecuador, which fitted both prerequisites perfectly, being as biodiverse as at least any other Latin American country and also one of the smallest to travel between interesting zones. The coastline seemed at least partly dive-able, and Ecuador was one of the most cost effective places to embark on a long Spanish speaking course. So it was then, and after a rather intensive initial set of weeks in the language classroom, that I decided to take a break to the coast and go diving.

Not having dived many exotic places before, the diving on Ecuador’s coast seemed considerably better than that of my murky home waters of the United Kingdom, so I quickly decided this was the place to begin and develop my professional diving career. Although I lived in Quito where I had just met my future wife, I began PADI divemaster and instructor training with one of the coastal dive schools, readily accessible by a short internal flight or not so easily reached by any of the frequently robbed or crashed national bus services.

Meeting a manta

During 2005, I dived quite a lot at Isla de la Plata and quite by chance sighted a giant manta. I shall never forget it.

Some of the local guys had said there might be a chance to see them there, but I was expecting something a lot smaller. I distinctly remember that individual. It was one of the less common melanistic or black mantas. Its cephalic fins were unfurled in front of its almost indistinguishable eye, giving it something of an elephantine appearance. It swung about us in two or three sweeping, purposeful passes. It seemed so immense, when it went over our heads it felt like night had fallen. There was an almost ominous, overbearing sentiment to its presence. Then it was gone. The sound of my regulator returned to my senses, hissing and wheezing—a comforting sound after the shattering boom of emotion that had wrung my head of any other thought when I saw that giant black shape.

Once I had settled back on the boat after that dive, my minded drifted back to my childhood when I had first learned of manta rays on television. Jacques Cousteau had described one saying that it appeared to him as a ghost, coming to him out of the gloom from who knows where, and going off to some equally mysterious and unknown place. His words could not have been better spoken. I was mesmerised, not only by the manta’s presence, but also the questions that came to my head.

This huge animal, quite obviously not a local resident and by all accounts only ever seen around that area for a couple of months, was full of mystery. I searched in Internet for any information that I could find on them and started to take photos of each individual. Their ventral surface is uniquely marked and if enough information is gathered, population estimates can be made by measuring sightings and comparing re-sightings against new individuals.

Local knowledge was indeed slim on the subject of these mantas, and the general consensus was that there may be something between 20 and 30 individuals (even to this day, it is very unusual to see more than a handful of these mantas at the same time).

Each time I dove the area, I would look out for and capture photos of the mantas, and my excitement soon mounted. After two seasons of casual attempts at identity shots, I had recorded no less than 40 individuals, and what everyone considered to be the ‘one’ black manta, turned out to be one of three melanistic mantas at that time. There had to be more.

I recounted my findings to a visiting scientist from the United States, Dr Jim Lehmann who was in the area working on whale migration with local whale researcher, Dr Cristina Castro. Jim was highly supportive of my initial enthusiasm and suggested one way to fund further investigation was to look out for volunteers recently graduated from university, or those looking to volunteer for a gap year.

These newly qualified biologists could supply some funding by paying a cost covering fee, and they would also bring some much needed biology knowledge to the field.

Identifying mantas

In 2009, Jim put me in contact with my first volunteer, Stacy Bierwagen who was taking a semester break from her marine biology degree course. During that summer, we got on whatever boat space that was available and spent as many hours on the key sites as we could.

Those early days were simply incredible. On occasions, there were more mantas than we could ID sensibly. Mostly though, the days were a little quieter.

Back then, dive tourism operated off the back of whale watching and walking tours to Isla de la Plata, with divers hitching a lift and diving when the walkers were on the island. Stacy and I were often the only divers in the water, with the mantas to ourselves. Our evenings were spent wading through ID shots collected on these diving days, and at the end of the 2009 season, we compiled a report that was submitted to the Machalilla National Park and Ministry of Environment.

Our conversations during that period were mostly raw and intense. Arguments over reasoning were common as we gleaned what little information we could from sparse Internet articles and the few scientific papers that we had access to.

In the few short years since 2009, it now seems ridiculous how little we knew, or even the world at large knew, about manta rays. One thing we did know was that there were a lot more than 40 mantas in that population. We had collected 101 new ID’s in 2009 alone and had not seen one single manta ray from previous years. Our recent accounts showed that we did not re-sight any one manta at the site for more than a handful of consecutive days, meaning each individual was not hanging around for very long.

Our driving force was always what was happening on the beaches, as we made our way from the scruffy streets of Puerto Lopez to the boats. The fisherman’s landing zone is in the same place as where all the whale watching tourists board their various craft. The looks on the western faces as they view the carnage is invariably either one of new romanticism beholding the rustic life of the local fisher folk or aghast environmentally aware travellers who are horrified to see row after row of shark and ray bodies hauled from the fibreglass pangas to feed local ...

(...)

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #47

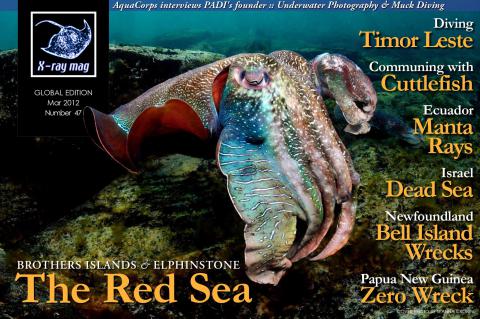

Red Sea travel special: Brothers Islands, Cairo to El Quseir, Elphinstone; Interview with Archim Schlöffel; Communing with cuttlefish; Kimbe Bay’s Zero Wreck; Bell Island wrecks; Hooded nudibranchs; Giant manta rays of Ecuador; Diving Timor Leste; How to photograph sharks with Andy Murch; Interview with PADI co-founder, John Cronin; Muck diving photography with Lawson Wood; The Dead Sea; Plus news and discoveries, equipment and training news, books and media, underwater photo and video equipment, turtle news, shark tales, whale tales and much more...

..