High Arctic

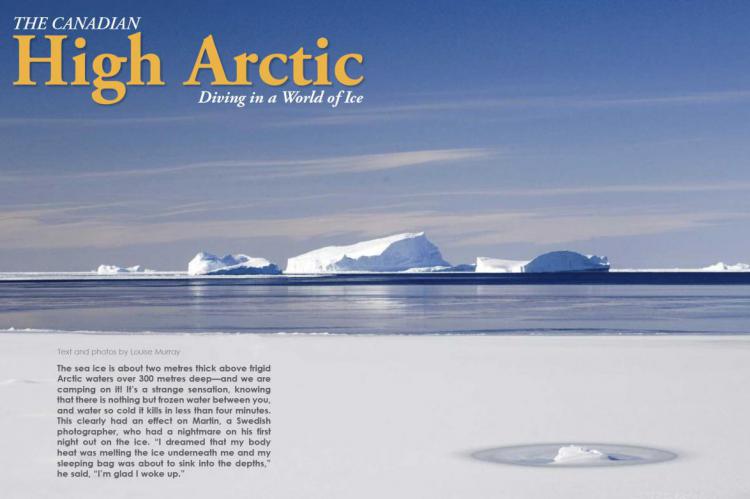

The sea ice is about two metres thick above frigid Arctic waters over 300 metres deep—and we are camping on it! It’s a strange sensation, knowing that there is nothing but frozen water between you, and water so cold it kills in less than four minutes. This clearly had an effect on Martin, a Swedish photographer, who had a nightmare on his first night out on the ice. “I dreamed that my body heat was melting the ice underneath me and my sleeping bag was about to sink into the depths,” he said, “I’m glad I woke up.”

Leaving Ottawa in the throes of a sultry 28 degree heat wave, our next landing is at Iqualuit, some four hours later, where a quick foray outside into freezing temperatures for a cigarette, confirms our arrival in the high arctic. A couple of other stops in Nunavut, a Canadian Territory, home to the Inuit people and six hours after leaving Ottawa, we land near the village of Arctic Bay where the temperature hovers around zero in the weak spring sunshine amid flurries of snow.

Everything that we will need for the next two weeks from shelter, food and bedding to compressors, fuel and generators has to be taken with us. The logistics are formidable, as we are venturing 100 miles out on to the sea ice. Our destination is Lancaster Sound, near the spot where Sir John Franklin perished in 1847 with all his men in the search for the North West Passage.

Ice Diving

Our first crack at a dive site starts with the largest Stihl chainsaw in the world, a 1.2 metre monster, Graham Dickson, expedition leader fires it up, a mad grin spreading across his face, as he does love his boy’s toys. Unfortunately, the easiest ice diving option was not to be, as after cutting three different holes near to an ice fracture beside camp, it is clear that the chainsaw is just not man enough to cut through the two-metre thick ice.

We load all the gear—cameras, tanks, ropes—on to the komoteks, or sleds, and head off to our next dive site option, a lead 10 km away. A lead is a crack in the sea ice that has opened and frozen shut leaving an area where the ice is much thinner, such that we can break our own entry hole to the water.

This is a serious overhead environment, and safety and redundancy in our diving is critical. “Everyone will be roped and dive in pairs initially. The second diver is responsible for signals to the rope tender on the surface,” says Graham to groans from the photographers who hate both ropes and diving with a buddy, “and if all goes well we’ll see about solo diving on the ropes. Compasses are unreliable this far north, so don’t use them.”

The water is a cool minus 1.8 degrees C, as cold as sea water can get before freezing. “I’ve never found the cold much of a problem,” says Australian Kelvin Aitken, “but then, I do have a lot of natural insulation there,” pointing to his belly and laughing, “anyway, your face goes numb as soon as you hit the water.”

All goes well on our first under ice exploration. The underside of the crack is intricately scalloped and corrugated by water and pockets are home to brown algae, sometimes dislodged in clouds by our bubbles. The lifeblood of the whole ecosystem, the pinkish krill, are easily recognizable, whizzing about like prawns on adrenaline. There are also many beautiful invertebrates, jellyfish pulsing slowly, and weird pteropods, a kind of snail, swimming by with two gracefully flapping ‘wings’.

Later, when diving the lead close to shore, we have a chance to investigate the bottom. It is teeming with life, brittle stars wave their arms at more than fifty to the square metre, and tube worms, nudibranchs and filter feeders of all sorts carry on their business next to red and green seaweeds. Far from mirroring the relative scarcity of species in the Arctic desert up top, this is an ecosystem that is exploding with life. I regret not taking a macro port for the camera. Next time perhaps. ...

Download the full article ⬇︎

Originally published

X-Ray Mag #12

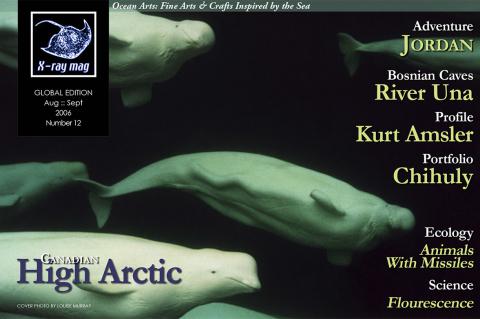

From cool blue wilderness of the Canadian high Arctic to the red hot deserts of Jordan - from Beluga whales close to magnificent wrecks. Also in this issue lots of Ocean Art including Chihulys Seaforms. Vi have a talk with photographer Kurt Amsler and AP Valves Martin Parker. Dives: 200m on CCR in Thailand and explore caves in Bosnia. Technique: Leigh Cunningham tells why we should watch our partial pressure and Jason Heller and Dan Beecham explains how we can rig your photogear.

Lots of other news and new gear too - as always.