A Holistic Approach to Coral Reef Health

Maintaining the good health of coral reefs is best done in a holistic manner, taking not just the physical health into consideration, but the environmental factors as well. A case in point: Following a major bleaching incident, corals on various reefs in Honduras and Belize recovered and grew normally within two to three years when the surrounding waters were healthy.

However, at locations were there was excessive adverse impact (like pollution), the corals did not recover fully, even after eight years.

“You can imagine that when you are recovering from a sickness, it will take a lot longer if you don’t eat well or get enough rest,” said Jessica Carilli, a graduate student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego.

“Similarly, a coral organism that must be constantly trying to clean itself from excess sediment particles will have a more difficult time recovering after a stressful condition like bleaching.”

Disease and overfishing also affected coral health. In places where there is overfishing, the population of bigger fishes like groupers are either significantly reduced or have vanished.

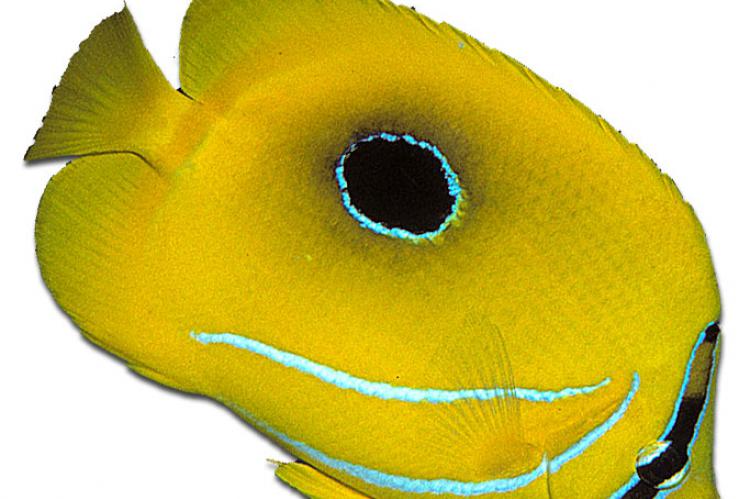

In the absence of these predatory fishes, other fish species thrive. One such species is the butterflyfish, which feed on coral and appear to be responsible for disease transmission amongst the corals.

In a study, scientists compared seven Marine Protected Areas [MPAs] where fishing had been banned for at least five years, and another seven neighbouring sites with similar diversity.

They discovered that the corals at the latter sites suffered more diseases; in some cases, the difference was twice as many. In addition, many butterflyfish were found at the sites where fishing was allowed, leading to a higher incidence of coral disease.

Similar patterns were found at the Great Barrier Reef in Australia.

Of course, other factors do come into the picture. Pollutants like sewerage and fertiliser are bad news for corals, as are the abnormally high water temperatures during the occurrence of El Nino.

Nevertheless, preserving the diversity of the reef appears to boost their ability to cope with certain rising temperatures.

“The general trend is that where you find more functional diversity, you find fewer butterflyfish,” reiterated Laurie Raymundo, a researcher at the University of Guam.

Of course, to ensure that predatory fishes are present to keep down the number of butterflyfish, the scientists are not advocating that fishing be banned. Rather, it is about maintaining a balance.

“One of the things that came out of this is that if you have a well-managed MPA, it works to keep coral healthier. [...] So as long you keep certain species there and can control fishing—don’t catch in certain seasons or don’t catch fish under a certain size, whatever is appropriate —you might not have to ban it completely.”

Similarly, a coral organism that must be constantly trying to clean itself from excess sediment particles will have a more difficult time recovering after a stressful condition like bleaching

—Jessica Carilli, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego.