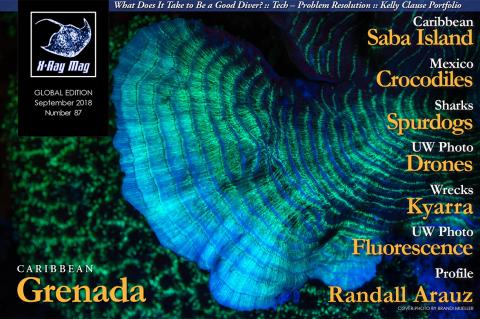

Mexico: American Crocodiles in Banco Chinchorro

The pursuit of unusual and compelling photo opportunities has led me on some interesting journeys over the last few years, but few come close to the raw excitement of photographing the American crocodiles of Mexico’s Banco Chinchorro! I have come to realise that photographing big and charismatic animals underwater actually borders on the addictive, because the more of those trips you do, the more encounters you hear about and the “must-do list” just keeps on growing. So it was when a conversation over an après-dive adult beverage led to the subject of in-water encounters with crocodiles.

Tags & Taxonomy

Being an Australian citizen, my thoughts were immediately drawn to the saltwater crocodiles of the Northern Territory, an animal that hits the headlines quite regularly because of its deadly attacks on humans. In the animal’s defence, it must be said that those attacks are often on either foreign tourists, who have completely ignored the very prominent “No Swimming” signs, or local guys out fishing who fail to understand the basic link between excessive alcohol and poor judgement around dangerous wild animals.

“Salties,” as we affectionately refer to them Down Under, take their name from the fact they are not limited to murky freshwater rivers and lakes, which most crocodiles are. Instead, they have developed a tolerance for salt water, which allows them to prowl coastal waters and occasionally swim quite far out to sea.

Thoroughly dangerous, there appears to be no way to safely photograph salties underwater, or even get close to them, except perhaps by using some form of motorised cage. As I was to learn, the less well-known American crocodile, is in fact a cousin of the Australian apex reptilian predator, which has also developed a tolerance for salt water. But unlike its antipodean relative, they are not considered to be aggressive to humans and only a few (unverified) cases of fatal attacks have been reported.

As its common name suggests, Crocodylus acutus can be found all the way from the Everglades on the southern tip of Florida, throughout the Caribbean and Central America, down to the northern end of South America in the countries of Ecuador, Columbia and Venezuela. In addition, its largest known population inhabits the land-locked hypersaline Lake Enriquillo in the Dominican Republic. But, by far the best place for reliable and up-close underwater encounters with the American crocodile is Banco Chinchorro in the southeast of Mexico, near the border with Belize.

Some 12 months on from that après-dive adult beverage, a lot of Googling and flurries of emails saw me sitting in a van driving south from Cancun International Airport on Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula (after the obligatory marathon journey from Asia) with a small group of like-minded characters I would come to know quite well over the next few days.

Banco Chinchorro

Although hardly a household name, Banco Chinchorro is, in fact, one of the largest coral atolls in the Northern Hemisphere and a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (see sidebar). Covering an area of almost 800 sq km, and located some 35km offshore, the reefs of Banco Chinchorro are very healthy and a real joy to dive.

But if it’s the crocodiles you are after, Cayo Centro is where you need to be. Although only just under 6 sq km in size, Cayo Centro is the largest of the three islands on the atoll and is home to a permanent estimated population of between 300 to 500 American Crocodiles. It also hosts a small, seasonal population of local fishermen who have built a scattering of about 10 huts on stilts, called palafitos, above the shallow waters of the lagoon on the eastern shore of the island and a similar number onshore called cabañas.

Quite how and when the crocodiles took up residence is not clear, but the dense mangroves of Cayo Centro offer the perfect habitat for them, with the rich waters around the island providing plenty of sustenance. The crocodiles and the fishermen have an almost symbiotic relationship, tolerating each other’s presence in this remote location with the main signal for interaction being the noise of the chopping tables.

The fishermen fillet their catches on tables above the lagoon at the palafitos (and at the water’s edge at the cabañas) and the crocodiles will immediately gather when they hear the knives on the chopping boards. For the crocodiles, it is snack time, while for the fishermen it is automated waste disposal.

How it works

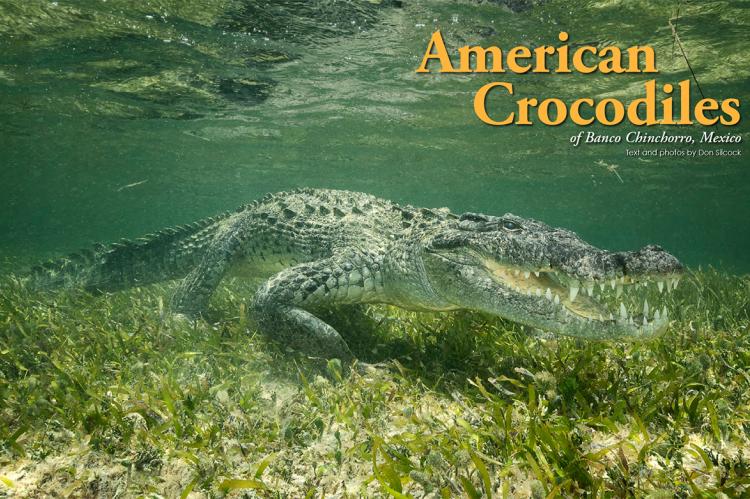

In-water encounters with the American Crocodiles of Banco Chinchorro are done on snorkel, as it is too shallow for scuba near the palafitos, plus it is easier to manoeuvre when unencumbered. Positioning and visibility are the key to safe encounters and our palafito had some prime real estate just in front of its main porch in the form of a large sandy patch that stretches out to the left of the hut.

Most of the lagoon has a rich coating of seagrass on the bottom, with which the crocodiles blend in perfectly when they submerge, making them hard to spot from the surface. The sandy patch makes it very easy to see who or what is there, and the basic concept is to keep the humans on the sandy patch and the crocodiles on the seagrass.

By mooring the boat alongside the palafito, one direction is blocked, and the sandy patch means that any crocodiles sneaking in can be spotted. By feeding them from the front of the boat, the “encounter zone” is quite well-defined and controllable. The actual control in the water is done with a wooden stick—albeit a large one—but a stick none-the-less. It is used by the wrangler to warn and calm the crocodile when it gets excited or aggressive, and as a vertical barrier if it advances on to the sand. Despite my initial doubts on its usefulness, it turned out to be remarkably effective.

Eyeball to eyeball

Of course, all those eminently sensible logistics were far from my mind as the time came to get in the water for the first encounter, and I was very nervous as I descended the ladder at the back of the boat that first time. Then, suddenly in front of you is a serious-looking piece of reptilian hardware that is watching you as intently as you are watching it. Inscrutable is the word that comes to mind.

Underwater encounters with big animals are rarely, if ever, static—they move, often constantly and occasionally very fast. In contrast, the American crocodiles of Banco Chinchorro remain completely still, but with a coiled-up energy that is unleashed when they attack.

The problem is that there is virtually no way of knowing when they will attack, so there is an intense tension as you manoeuvre closer to get good images knowing that should that trigger happen, you are very reliant on that wooden stick and the reaction time of the crocodile wrangler.

The crocodile whisperer

So how do you become the “guy with the stick” who is responsible for keeping guests safe and ensuring no harm comes to the animal—even PADI has yet to come up with a speciality course for that. In the case of Mathias Van Asch from Belgium—not a country normally associated with large and potentially dangerous reptiles—it was a case of being in the right place at the right time. Arriving in Xcalak as dive instructor, it turned out that the incumbent had decided to move on but stayed around long enough to provide some very hands-on initial training in the not-so-gentle art of crocodile wrangling.

With some three seasons under his belt now, Mathias freely admits that he was hyper-nervous the first time he got in the water with the Chinchorro crocodiles, but over time he has clearly identified certain key behavioural patterns—starting with the young ones, which are by far the most dangerous because they are unpredictable. The big crocodiles may look fierce and very threatening, but they are not particularly aggressive and tend to be much calmer than the young ones.

The golden rule is to never take your eyes off the crocodile—allow them space, but do not allow them to command that space by using the large wooden stick as a vertical barrier between them and the guests. Mathias believes that attacks do not happen because the guests, with their cameras and dome ports are the biggest things they have seen underwater, and their reflections in the dome ports basically confuse the crocodiles—so they are very wary.

Final words

Is it dangerous? Probably and possibly are the best descriptors, as there is no doubt that they could inflict serious harm, but nobody has been attacked. Is it special? Yes, for sure it is—being so close to such large and potentially dangerous reptiles is something else. Plus, the whole experience of staying in the fishermen's palafito hut with no running water and just a small generator for power is very different. Was it worth the marathon journey? Australia is a long way from everywhere, and a really long way from Banco Chinchorro—but yes, it was definitely worth the long haul. Would I do it again? Probably.

Asia correspondent Don Silcock is based in Bali, Indonesia. For extensive location guides, articles and images on some of the world’s best diving locations and underwater experiences, see his website at: Indopacificimages.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎