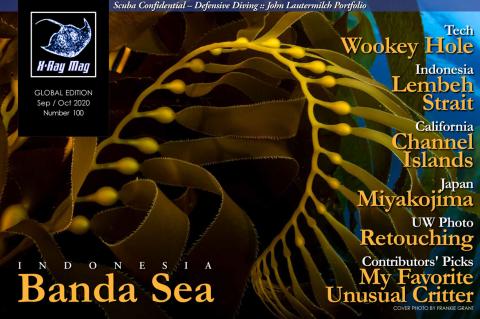

My Favorite Unusual Critter Dive: Contributors' Picks

We asked our contributors what their favorite unusual critter dive was and they answered with stories and photos of weird and wonderful creatures, big and small, giving first-hand accounts of their often bizarre behaviors under the waves.

Photo by Matthew Meier: A tiny clown frogfish is a juvenile version of a warty frogfish, Lembeh Strait, Indonesia. Exposure: ISO 200, f/29, 1/125s. Camera gear: Nikon D810 camera, Nikon 105mm macro lens, Subal housing, two Sea&Sea YS-250 strobes and homemade snoots

Tags & Taxonomy

X-Ray Mag contributors reveal the strange, rare or other-worldly yet endearing denizens of the underwater realm—from the topical paradise of Indonesia and the Philippines to the temperate waters off California, British Columbia, South Africa and South Australia, to the frigid waters of the Barents and East seas off Russia—where they captured images of their favorite critters.

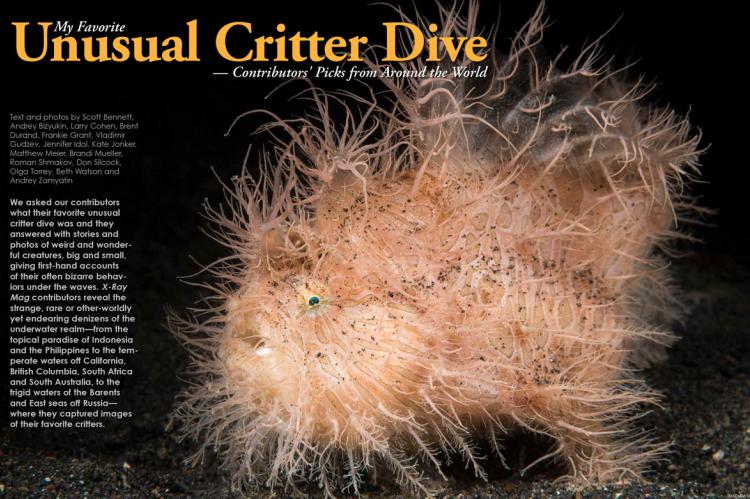

Frogfish

Text and photos by Matthew Meier

One of my favorite critters is the frogfish. Part of the anglerfish family, these lay-in-wait, ambush predators come in a variety of colors, textures and patterns, all designed to help them blend into their environment. The camouflage helps frogfish elude predators and also hide while attracting prey with the use of their lures. When a target is within striking distance, they open their mouths and fully engulf their meals, which can be up to twice their own size, in as little as six milliseconds. The assault is so rapid that it is difficult to see without the aid of slow-motion cameras. Tiny frogfish that can be found on the reef can be smaller than a pinky fingernail, while the giant frogfish is as large as a soccer ball when fully grown. I am fascinated with the hairy frogfish, also known as the striated frogfish, and am compelled to take photos whenever I am lucky enough to find one. Thanks go to Atlantis Dive Resorts and Liveaboards (atlantishotel.com) and Solitude Liveaboards and Resorts (solitude.world) for hosting these photo adventures. Please visit: MatthewMeierPhoto.com

Harlequin Shrimp

Text and photos by Scott Bennett

To the uninitiated, it is difficult to comprehend what you are even looking at. Brandishing paddle-shaped claws and a cream-coloured body patterned with red, purple, orange and blue spots, harlequin shrimp must be one of the most photographic critters in the sea. Reaching about 5cm in length, harlequin shrimp reside throughout the tropical Indo-Pacific. Despite their compact size, they have few natural predators, likely due to toxins present in their bodies. Bright colouration is usually a warning to predators, so the harlequin shrimp is a neon billboard! (Wikimedia)

Its benign appearance masks a grisly character. Living in pairs, harlequin shrimp feed exclusively on sea stars, including the notorious crown-of thorns starfish. Upon detecting the scent of their prey, they work together to flip the starfish on its back, consuming the tube feet and the soft tissues. If unable to right itself, the starfish will then face the prospect of being eaten alive for a period up to two weeks. (Wikimedia)

I saw my first harlequin shrimp at the Seraya Secrets dive site on Bali’s east coast. Swimming along the black volcanic substrate, the impossibly gaudy colouration stood out like a sore thumb. A pair of harlequin shrimp had captured a starfish and were in the process of severing an arm. Utterly preoccupied, they took no notice of my camera, allowing me to fire off a number of images. I was thrilled. The starfish? Not so much. Please visit: xray-mag.com/contributors/ScottBennett

Diving Guillemots

Text and photos by Andrey Bizyukin

Land, sea and air—the three domains on Earth. Are all three realms accessed only by special forces SEAL teams or curious, playful seals? No, as it turns out, there are other creatures on our planet that also claim access to all three domains. Intelligent, inquisitive, omnipresent, merciless hunters and far more agile, they are the diving birds. I have travelled the world in search of places where I could observe and photograph these seabirds in their natural habitat. After trips to South Africa, Antarctica and the Galapagos Islands, I finally found that Kuvshin (Jug) Island in the Kandalaksha Nature Reserve, located in the Barents Sea of Russia, was the best and most affordable place to successfully photograph diving birds. In summertime, guillemots and puffins migrate to their nesting places in the Russian North. When their chicks hatch, adult birds begin to hunt for food for them, flying over land and sea and diving under the water. They will dive to depths up to 30m in search of fish. I participated in a few dive trips over several years to find the right time, weather and conditions to which the birds were accustomed, and which offered a chance to observe and photograph them. The seabirds usually avoided divers, but curiosity often took over and they would quietly begin to watch divers from behind. Underwater, the birds were super-fast, their movements lightning quick. Their dives lasted only a few seconds, during which time they flashed in front of the camera and then disappeared again into the dark depths, leaving you in the empty sea for a long time, waiting and hoping for another encounter. To get lucky shots, I had to do several 1.5- to 2-hour dives in icy waters of 4°C. I used a TTL converter by UW Technics, which really helped a lot. Thanks to this device, most of the images captured were of good quality and had the right exposure. Please visit: xray-mag.com/contributors/AndreyBizyukin

Wolf Eel

Text and photos by Larry Cohen

Divers in the North American Pacific Northwest consider wolf eels to be very common. But as a diver from the US Northeast, they had been on my bucket list for many years. In 2013, my desire to photograph and interact with these animals came true in British Columbia, Canada. All the walls underwater there teemed with life. This was where I spotted my first wolf eel. These creatures have a face only a mother could love. Wolf eels mate for life. They can grow up to 2.4m (7ft 10in) in length and weigh as much as 18.4kg (41lb). Wolf eels differ from true eels in that they have paired gill slits and pectoral fins (Wikipedia).

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and these gentle fish have a charming personality. They feed on invertebrates with hard shells, including sea urchins, mussels and clams. Wolf eels are able to crush through the shells with their strong jaws. Not aware of this fact, my dive partner Olga Torrey and I opened and fed sea urchins to our new wolf eel friend. But our new buddy gently grabbed the sea urchins from our hands. It chomped through the hard shell and spines with its powerful jaws. At that time, I was shooting with the Olympus E-620 DSLR in the Olympus PT-E06 housing. The lens was the Olympus 7-14mm four-thirds lens and I used two Olympus UFL-02 strobes for lighting. Please visit: liquidimagesuw.com

California Harbor Seal

Text and photos by Brent Durand

California harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) never cease to capture my full attention. Many of my saltwater friends can recount magical interactions with these shy pinnipeds; however, I rarely seem to have that luck. I usually see a flutter or a shadow in the distance and know it is a seal, based on its movements—then, nothing more. But one day in Malibu, that all changed. I found myself spending an hour freediving with a curious but shy seal, which I had seen around the reef in recent weeks. I ran to the car, switched to scuba, grabbed my camera, and finally, the seal came up to play, like a timid puppy. It nibbled on my fins, inspected what I pretended to find very interesting, and just had a great time. It followed me to shore, once I had to go, but then became shy when I swam out with my next tank. I welcome all seals to join me on any dive! Please visit: tutorials.brentdurand.com

Angelshark and Garibaldi

Text and photos by Frankie Grant

A couple of my favorite unusual critter dives took place off the coasts of the US state of California and the Mexican state of Baja California. La Jolla Shores is quite famous in Southern California for its remarkable night shore dives and unique wildlife encounters. One such creature, the Pacific angel shark, can be seen here resting on the sand. They will bury themselves into the sand, perfectly camouflaged, and hunt fish under the cover of darkness. When people think of the Coronado Islands in Mexico, the sea lion rookery is usually the highlight. But, tucked amongst the rocks is a thriving ecosystem, including sheephead, kelp bass and Garibaldi fish. The Garibaldi, pictured above, is guarding its nest under a rock ledge. One can see several bite marks where other fish have preyed upon the eggs. It is quite intriguing, though, how the rock on which the nest was laid had a bit of a heart shape. Please visit: frankiegrant.com

Giant Pacific Octopus

Text and photos by Vladimir Gudzev

On one particular dive off the Russian coast on the northern end of the East Sea (also known as the Sea of Japan), in the vicinity of Ore Pier, my dive partner and I searched the sandy sea bottom dotted with rocks at a depth of 22m, with a specific purpose—we were hoping to meet octopuses. In this place, two varieties of octopus were usually found: the giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) and the sandy octopus (Octopus conispadiceus). Giant Pacific octopuses can grow up to 5m in length and up to 60kg in weight, but this is rare. They usually reach around 20kg. In contrast, the sandy octopus is small, weighing usually about 4kg.

Octopuses can be found at a depth of about 20m, where the water is cold (6-10°C). On this dive, which took place in September, water temperatures at the surface were 17-20°C. As we searched the sea bottom, we accidentally scared a large octopus, apparently a giant Pacific octopus. There was a dignity and elegance in its behavior as it displayed its abilities in mimicry, moving, swimming, taking threatening postures and releasing ink. And then, it disappeared into the crevices of the rocks. We were lucky to capture a shot of it.

Vladimir Gudzev is an avid diver and underwater photographer based in Moscow, Russia.

American Paddlefish

Text and photos by Jennifer Idol

I first learned of the American paddlefish (Polyodon spathula) during my 50-state journey, diving in each state of the Union [Ed. – see the author’s book, An American Immersion]. Listed as a vulnerable species, they are the last of their kind. The Chinese paddlefish was declared extinct last year, leaving this prehistoric wonder as the only living relative. This living fossil dates back to the Early Cretaceous and is closely related to sturgeon, another primitive fish. Once prolific, these fish are hunted for their unique shape and roe. They were extinguished from their original northeastern habitats in the United States. They live in rivers and are supported as a species by hatcheries. Since a current is required for them to reproduce, damming of rivers has further reduced their population. Similar to basking sharks, these fish are filter feeders and can be seen swimming through murky water filtering zooplankton. I return annually to lead a trip at Loch Low-Minn quarry lake in Athens, Tennessee, to share the experience of encounters with others. Please visit: uwDesigner.com

Rare Flatworm and Nudibranch

Text and photos by Kate Jonker

Named for its distance from the land rather than for being particularly deep, Steenbras Deep is a vast reef, running parallel to the eastern coast of False Bay, South Africa. Life here is extraordinary and rare critters abound—from crazy, grey elephant-ear-like sponges and seldom-seen Mandela’s nudibranchs (Mandelia mirocornata), to weird smooth horsefish (Congiopodus torvus) and snakehead toadfish (Batrichthys apiatus). One of the most fascinating and unusual critters you will find is a tiny, white, undescribed species that can morph into various shapes—reminding me of a 4mm-long “Casper the Friendly Ghost” from my childhood comic books. Although referred to as an Acoel flatworm, this species has local marine biologists stumped as it does not have a stomach and verdict is still out as to what it is. Steenbras Deep is an exciting dive as one never knows what rare and unique critters one will encounter—but one thing is certain, you can expect the unexpected! Please visit: katejonker.com

Tongue-Eating Louse

Text and photos by Brandi Mueller

Like something out of a horror movie, the tongue-eating louse is an underwater creature out of a nightmare. These parasitic isopods access the fish through the gills and attach to its tongue, slowly digesting it until the isopod basically becomes the fish’s tongue. These isopods can be found in many places around the world, but nowhere else in my dive travels have I found them to be so prolific, and also a bit specific, as in Indonesia. Many clownfish and anemone fish in Indonesia’s Lembeh Strait seem to be suffering from these parasites. Often, they open their mouths and we can see two tiny eyes looking back at us. Ouch! Not all isopods take over tongues though; the longnose hawkfish in Raja Ampat, Indonesia, has one living on the outside of its body. Please visit: brandiunderwater.com

Very Rare Blue King Crab

Text and photo by Roman Shmakov

On a recent trip in early summer, my dive partner and I traveled along the eastern coast of the Barents Sea. The Gulf Stream cools down and ends at this point; hence, underwater life here is even richer and more diverse than in Norway. In the open sea, just opposite the local village of Teriberka, we descended down to a depth of 15m in cold clear water with a temperature of 4°C. We found a large company of king crabs waiting for us at the bottom.

Once upon a time, biologists had brought these crabs here from the Pacific Ocean and now they have completely taken root. King crabs are very active at this time of the year. They protect their territories on the seabed and attack each other and even curious divers. For some reason, I spotted one very large crab of blue color and decided to photograph it close-up. The crab took on a terrifying pose and came at me, fearlessly, threatening me with its huge claws—maybe because it saw its reflection in the dome port of my camera and mistook it for another male.

At the time, I was afraid it might cling to me and bite off my regulator hose or flash cables, but my dive buddy understood what was going on and tried to distract the crab, and at the same time, illuminate it with a red light. This was how the shot of the attacking crab came about.

Later, I learned that I had, in fact, taken a unique photo of a very rare blue crab (Paralithodes platypus), which usually live at a depth of 100 to 300m, can reach 5kg in weight and live up to 25 years. Marine biologists told me that it was a real achievement to meet and photograph such a unique creature underwater in its natural habitat.

Guest contributor Roman Shmakov is an avid diver and underwater photographer based in Moscow, Russia.

Australian Giant Cuttlefish

Text and photos by Don Silcock

“What’s your favorite unusual critter dive?” Sometimes, it takes a really obvious question to make you realize just how good your own backyard is. About six years ago, I got the “big animal” bug and started to travel great distances to experience and photograph some of the incredible aggregations that occur each year around the world. Those journeys took me to the Bahamas (three times), both coasts of Mexico, the Azores, South Africa (three times), Tonga (twice) and Japan (twice) as I sought to capture what happened at those special and quite unique events. I also returned to Whyalla in South Australia, where each year tens of thousands of giant Australian cuttlefish gather to mate.

Last year, I went back again to fulfill a promise made during the Sardine Run in South Africa to my great Italian diving buddy Filippo Borghi (instagram.com/filippoborghi5) that I would show him what I consider to be the finest that Australia has to offer underwater. It was the best trip ever and it is now obvious to me that in terms of getting close to incredible animals during a special moment in time (for them), it is my favorite unusual critter dive!

Space does not allow for why so many cuttlefish gather and what exactly is going on, besides the basic theme of “it’s sex at its most rampant,” but trust me, it is an incredible spectacle to observe. There is a full explanation, together with some of my best images, available on this link to my website: The Australian Giant Cuttlefish.

Ocean Sunfish (Mola mola)

Text and photos by Olga Torrey

Our goal, while snorkeling off Montauk, New York, USA, was to photograph blue sharks. This trip turned into a once-in-a-lifetime experience. A curious adult blue shark stayed with us for three hours, to our delight.

We were all back on the boat, getting ready to head back to the shore, when, suddenly, an ocean sunfish (Mola mola) appeared on the stern side of our boat. My friend Sandra and I jumped back in the water. This fish is native to temperate waters around the world (Wikipedia), and I knew they existed in the waters of the Northeast. I had always wanted to photograph one, and here was my chance.

Ocean sunfish are one of the heaviest known bony fishes in the world. Adults typically weigh up to 1,000kg, or 2,205lb (Wikipedia). The one I encountered, was a small juvenile, but still impressive. It is hard to believe that a fish this flat could weigh so much. The magnificent creature stayed with us for only a few minutes. This did give me enough time though to take photographs with my Olympus OM-D E-M5 camera in a Nauticam housing. I used the Panasonic Lumix G fisheye 8mm f/3.5 lens and Sea&Sea YS-D1 strobes for lighting. Please visit: fitimage.nyc

Eels and Octopuses

Text and photos by Beth Watson

The Nudi Falls dive site in Lembeh Strait, Indonesia, is amazingly diverse and one of my favorite dives for macro critters. There is a short mini-wall in the shallows, which is home to a wide variety of marine life. A rocky reef and sandy slope extend out from the wall, providing a plethora of exotic, weird and wild critters to photograph. There is a beautiful soft coral garden, beginning at around 20m, which extends into deeper water. The area is a hotspot for rich marine life and biodiversity. Nudi Falls can be dived time after time, and it never gets tiresome. Divers will be awed and astounded by the life found on each and every dive. It’s a mystery—you never know what will pop up! Please visit: bethwatsonimages.com

Lemon Sharks

Text and photos by Andrey Zamiatin

Tiger Beach, located in the Bahamas, is well-known for offering unique opportunities for shark photography in natural conditions without cages. The Dolphin Dream, which departs from West Palm Beach, provides keen underwater photographers a chance to take photos of lemon sharks. The photo shoot in which I participated took place during a feeding frenzy, when sharks were fed grouper fish heads, right next to us divers. Special care and detailed instruction were required to do the dive.

These yellow-skinned beauties live in the warm waters of the Caribbean Sea, not far from the Gulf of Mexico and the Bahamas archipelago, sometimes moving on to the Atlantic Ocean. The short-winged, sharp-toothed shark got its name from the light brown color of its huge 3m-long body, which helps it to disguise itself on sandbanks.

Lemon sharks have interesting character traits. They also have good memories. By the way, it is the lemon shark that has the highest intelligence among the various shark species. Indeed, it is a species that can seem very vengeful. There is a well-known case that occurred on the reefs, in which a lemon shark, after a skirmish with a Caribbean shark, furiously attacked all the reef sharks swimming in their usual territories. In principle, the lone short-winged lemon shark quite simply provoked an attack. A lemon shark will attack—not interfere, but attack—other sharks. That is why these sharp-toothed predators can claim their rightful place on the list of formidable sharks. However, lemon sharks are a threatened species due to overfishing and predation. There is, unfortunately, high demand for their skin, fins and meat.

Guest contributor Andrey Zamiatin is an avid diver and underwater photographer based in Moscow, Russia. Please visit: zamiatin.com

Download the full article ⬇︎