Out of Air with Plenty to Breathe

It was a beautiful day in Indonesia’s Banda Sea. Richard rolled back into the warm waters and swam over to join his wife, Florence. After exchanging signals, they descended together, heading for a patch of bright yellow sea fans on the reef wall at 30m, where their guide had promised to show them pygmy seahorses. The guide was already there below, searching for the elusive little creatures. But, as Richard gradually went deeper, he began to find it harder to breathe and he was soon having to expend significant effort to suck air from his regulator.

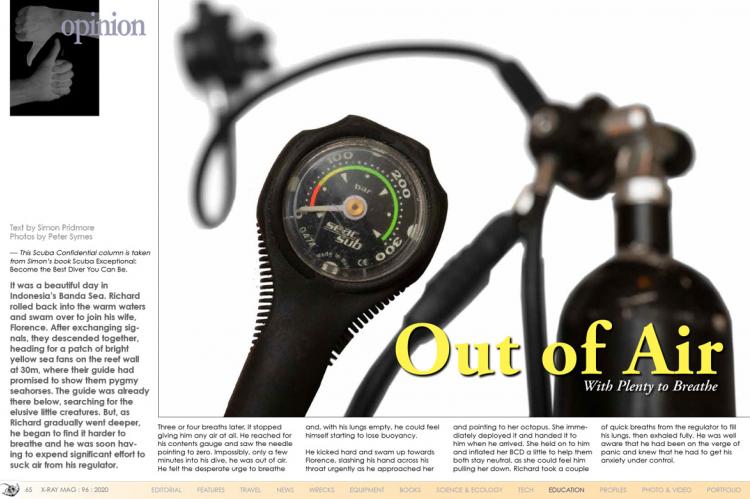

Three or four breaths later, it stopped giving him any air at all. He reached for his contents gauge and saw the needle pointing to zero. Impossibly, only a few minutes into his dive, he was out of air. He felt the desperate urge to breathe and, with his lungs empty, he could feel himself starting to lose buoyancy.

He kicked hard and swam up towards Florence, slashing his hand across his throat urgently as he approached her and pointing to her octopus. She immediately deployed it and handed it to him when he arrived. She held on to him and inflated her BCD a little to help them both stay neutral, as she could feel him pulling her down. Richard took a couple of quick breaths from the regulator to fill his lungs, then exhaled fully. He was well aware that he had been on the verge of panic and knew that he had to get his anxiety under control.

As he breathed deeply in and out, his mind cleared, and a habit formed during his technical diving training kicked in. With his left hand, he reached back and pushed the bottom of his cylinder up, bringing the valve handle within touching distance of his right hand. His first instinct was to turn the valve handle away from him—that is, to try and open it—in spite of the fact that he expected it already to be fully open. To his surprise, not only did the valve handle move when he twisted it, it kept moving for quite a while before it locked. He glanced at his contents gauge. It was showing 160 bar.

He switched back to his own regulator and took a tentative breath. The air flowed easily. He thought about abandoning the dive but there now seemed to be no reason to do that, so he and Florence carried on down to look at the seahorses. The emergency was over, but Richard was left with plenty to think about.

How could this have happened?

He was bewildered. Surely, his valve must have been open when he started the dive, otherwise, he would not have had air to breathe during the first few minutes. He dismissed the possibility that Florence might have crept up behind him and closed his valve as a prank. She would never do that. He then thought that perhaps there was something wrong with his regulator. But it had been working perfectly throughout the trip up to the point when it stopped giving him air, and it had continued to work perfectly after he had re-opened his cylinder valve. It was only much later that he deduced what must have taken place.

When he had put his gear together on the boat, he was sure he had fully opened his cylinder valve, as was his usual practice. However, on this particular day, there was a temporary and relatively inexperienced crew member on board. This person had helped Richard, Florence and the other divers into their gear, and Richard had noticed him turning other divers’ air on.

What must have happened, thought Richard, was that the helpful crew member had mistakenly closed Richard’s valve, thinking he was opening it. He had then twisted it back a quarter of a turn. During the first part of his dive, Richard was able to breathe from the cylinder, as the valve was slightly open. It was only when he went deeper that he began to have a problem, as the only-slightly-open valve could not supply the quantity of air (usually 9 bar or so above ambient pressure) required to keep the regulator working at depth.

Had the crew member closed the valve completely and not turned the handle back a little, Richard would have discovered the problem while he was still in the boat or on the surface waiting to descend, as he used up the small quantity of air left in his regulator hoses. So, here we have another argument for abandoning the antiquated practice of routinely closing a cylinder valve by a quarter- or half-turn after opening it, something new divers are still taught to do, entirely unnecessarily, as I have pointed out before.

Useful techniques

Two factors turned what could have been a tragedy into simply a useful story. The first was Richard’s controlled response to the emergency, borne out of good diver training. Although this was not a technical dive, the instinctive skills he had learnt during his technical diver courses came in very handy. The second factor was Florence’s commendable readiness to assist. She was a new diver at the time but responded like a veteran. She and Richard practised sharing air frequently, so she was used to it.

Messages to take away:

- 1. Take responsibility for opening your own cylinder valve before a dive. If someone else wants to do it for you or touches it to check it is open, politely refuse. Then, show them that it is fully open by double-checking it yourself and taking a few breaths from it while looking at your contents gauge to make sure the needle does not move when you breathe in and out. (If it moves, that means you have an air supply problem).

- 2. If, nevertheless, you ever find yourself out of air early on in a dive, do what Richard did. First, find someone to share air with. Then, reach back and check that your cylinder valve is open, just in case some well-meaning person has left you out of air with plenty to breathe. ■

This Scuba Confidential column in issue #96 was taken from Simon’s book Scuba Exceptional: Become the Best Diver You Can Be.

Simon Pridmore is the author of the international bestsellers Scuba Confidential: An Insider’s Guide to Becoming a Better Diver, Scuba Professional: Insights into Sport Diver Training & Operations and Scuba Fundamental: Start Diving the Right Way. He is also the co-author of Diving & Snorkeling Guide to Bali and Diving & Snorkeling Guide to Raja Ampat & Northeast Indonesia, and a new adventure travelogue called Under the Flight Path. His recently published books include Scuba Exceptional: Become the Best Diver You Can Be, Scuba Physiological: Think You Know All About Scuba Medicine? Think Again! and Dining with Divers: Tales from the Kitchen Table. For more information, see his website at: SimonPridmore.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎