Photographing American Crocodiles in Cuba

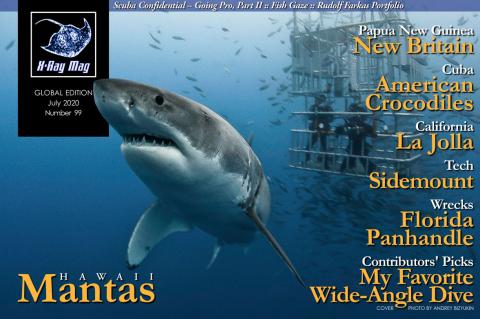

The Gardens of the Queen is a popular and iconic dive location in Cuba for those underwater photographers who have creative ideas for documenting or capturing artistic images of sharks, groupers, crocodiles and other fauna of the Caribbean Sea. Here, it is possible to film life in the mangroves, and if one is lucky, meet a crocodile. Vladimir Gudzev reports.

Tags & Taxonomy

Dear lovers of underwater photography, I’d like to tell you a story about a unique expedition and photo safari in which fellow participants and I were lucky enough to develop a successful method of taking underwater photographs of marine crocodiles at Cuba's Gardens of the Queen. This site is located far from urban areas and protected from storms and currents, but the accommodations are very comfortable.

Usually, visitors get to Havana by plane, then travel by a comfortable bus across half the country to the southeastern port of Jucaro, where a large ship awaits. This vessel can comfortably accommodate up to 30 divers and guests, and is quite fast. The ship’s special dive boats are used to bring divers to specific dive sites.

Diving

The daily diving schedule was as follows: 6:45 a.m., get up; 7:00 a.m., get to the dive site; 7:30 a.m., first dive; 9:15 a.m., breakfast; 11:30 a.m., second dive; 1:00 p.m., lunch and rest; 3:30 p.m., third dive; 6:30 p.m., dinner; and finally, at 7:45 p.m., a night dive. The water temperature was about 30°C (86°F), which allows you to dive in a thin wetsuit or even just a Lycra dive skin. The visibility of the water varied from 15m to 20m. Diving depths were no more than 30m, with most dives reaching only 20m. Dives lasted no more than 50 minutes.

There were really a lot of sharks here. They were quite bold, getting close to divers and often accompanying them up to the very surface. Gray reef sharks stayed mainly at a depth of at least 10m, and silky sharks stayed in the region of one to seven meters.

Sometimes, it seemed quite dangerous—especially when you had to exit the water along the gangway, among swarming sharks, pushing their bodies out of the way with your body. It was scary, and then there was the blood from the fish baits, dripping from the deck. Our Cuban dive guides just chuckled, asking us not to wave our hands. But nothing happened!

How to photograph a sea croc

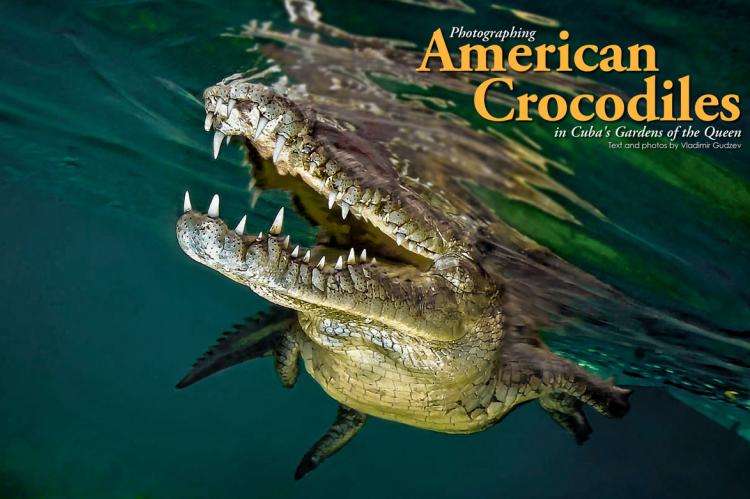

However, the more important story here is how we photographed a sharp-snouted American crocodile in the mangroves. Photographing a sea crocodile is actually a main objective for many underwater photographers, and we were no different.

The depths at the site were shallow—from one to two meters. There was little current. Water visibility was five to ten meters, depending on how much silt a diver’s finning technique disturbed from the sea bottom. But the current carried away the silt within minutes. As a rule, we arrived at the site at 11:00 a.m., baring gifts for the crocodile—frozen pieces of chicken.

Settling the dive boat in the right channel among the mangroves, our Cuban dive guides began shouting loudly, “Ninyo!” (“Boy!” in Spanish) and splashed the chicken on a rope into the water. The first time, we waited for a crocodile to appear for about 20 minutes and even lost hope. But then, we Russian participants followed the Cubans' lead and started shouting: “Genie, come out! Hey, you! Come out, floating log! Tram-ta-ra-ram!”

And “His Excellency” appeared from the mangroves, leisurely swimming to the boat, where on the side, a piece of chicken splashed seductively. As it swam, the whole group of us divers (having forgotten our initial fears) gleefully jumped into the water, cameras in hand. There was no organization here: crocodile, flippers, arms, chicken and photo equipment were everywhere, flailing and causing the sediment to rise up, clouding the site. In short, it was 39 minutes of chaos. In the end, the cheeky crocodile stole the chicken and escaped into the mangroves! In the evening, we each reviewed our shots and got depressed. They were all just a mess.

A new approach

So, we decided to repeat the shoot, but firmly agreed on mutual understanding and coordination. Our Cuban dive guides gave us the go-ahead for another round, or as many as we needed. Dive guides and divers came up with a method devised on a human basis, and everyone agreed to the plan of circular shooting in turn. Each photographer was given two to three minutes to shoot, then the next one would take a turn, and in this way, we would avoid the crush and turbidity of the first experience. Doing this, we each could do several rounds, until the plan was exhausted. We could also watch our colleagues, and gain new perspectives.

For proper buoyancy in this type of shallow dive, we found that one needs to wear a belt with a couple of weights. One also needs to use a snorkel. Usually, diving here is done without scuba gear, and it is important to choose the right load on one’s weight belt.

On full inhalation, you should be able to float slightly, and upon exhalation by one-quarter, your buoyancy should become zero. This allows you to observe the crocodile from the sea bottom without touching the silty sea floor, but remain in the water column, thus avoiding lifting up sediment into the shot with your fins. In this case, you must very carefully sink to the bottom without raising turbidity, taking into account any water current. It is also a good idea to consider the position of the sun in the sky for the desired lighting effect in your shot. Lastly, one has to adhere to agreements and not interfere with colleagues.

In addition, we followed the directions of our Cuban dive guides, who ensured the safety of the dives. All the same, the mouth of this crocodile “Ninyo,” and the teeth found therein, were a terrifying sight.

This time, the crocodile was ready. Apparently, it really liked yesterday’s chicken, and it immediately swam toward us. Then, each of us took turns implementing and polishing our individual shooting techniques to get the shots we wanted. We each did at least two rounds, sometimes three. Visibility remained clear, and our Cuban dive guides ensured dive safety from the side of the boat, watching from above. In case a tricky situation arose, the crocodile could be led away with a long pole (resting on the tail) to the side or back. The process went well, and everyone got the full program.

In short, it was both scary and funny. On one attempt, I tried to get closer to this reptile, by 30cm, and it came to me on its own. At this point, our dive guide pulled it back a little, very carefully, several times with the pole. It was a bit odd, watching the crocodile, poking out its talons, rowing its legs and feeling out of place—it seemed like it was yelling expletives. Then, it gaped as the chicken teased it. The mouth is just creepy, especially when it was opening and drawing closer. For some of my other colleagues, the crocodile simply clung to the acrylic spherical port, or discharge port, of the dive boat.

Afterthoughts

While there were moments that felt on the verge of being a circus, ultimately, everyone got quite decent results from their photo sessions with the crocodile. Well, some footprints were visible in the photographs, but I think that this experience was useful to anyone who wanted to give it a try.

Yes, it was expensive, far away, and difficult to get a good shot, but it was a once-in-a-lifetime experience! The thrill was definitely unique—as were the photos we got in the end. ■

Vladimir Gudzev is an avid diver and underwater photographer based in Moscow, Russia.

Download the full article ⬇︎