SMS Friedrich Carl

The armored cruiser Carl Friedrich was constructed in the year 1902 at the well-known shipyard of Blohm & Voss in Hamburg, Germany. The armored cruiser had a length of 126m and was equipped with an impressive array of guns and torpedo launchers. She was the second ship of the Prinz Adalbert class when she was commissioned by the Imperial German Navy on the 12 December 1903.

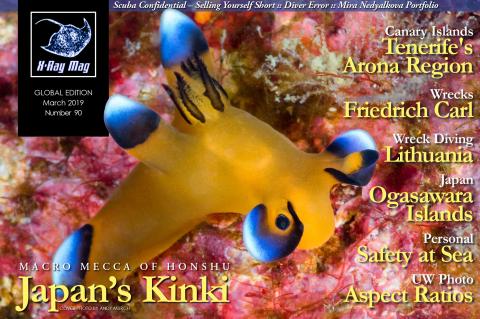

Canon on wreck of SMS Friedrich Carl, which is located off the coast of Klaipeda, Lithuania. Photo by Vic Verlinden.

In the early years, she served as a torpedo training ship. Because of her three engines, she could reach a top speed of 20 knots. During the outbreak of the First World War, she served as the flagship of Rear Admiral Ehler Behring. At this time, she was converted to carry two seaplanes. She was the first ship of the Imperial Navy able to carry and launch seaplanes.

At the start of the war, Behring was ordered to actively monitor the activities and movements of the Russian fleet in the Baltic Sea. To execute this mission, the Carl Friedrich was accompanied by several light cruisers and four destroyers. The squadron was operating from the port of Danzig but was not able to sail due to the bad weather.

An unexpected explosion

Despite the bad weather, the Russian minelayers had not been idle and had laid various minefields in the operating area of the Carl Friedrich. On 17 November, Behring ordered the continuation of the mission and the vessels left the port.

When the vessel was 30 miles away from the port of Memel (Klaipėda), it was struck by a heavy explosion. Immediately, the admiral gave the order to try all means to save the ship. Every possible measure to keep the ship afloat was taken; however, in the end, the abandon-ship order was given, and all sailors and officers left the ship. There were only eight deaths among the 557 crew members and officers, most of whom were taken on board the light cruiser Augsburg. A while later, the Carl Friedrich disappeared under the waves and sank to the bottom of the Baltic Sea. The loss of the beautiful warship was a heavy blow to the German navy, as the vessel could not be replaced immediately.

Dive operation in Lithuania

As early as 2017, I had decided to dive the wreck of the SMS Carl Friedrich, but due to circumstances, this trip was postponed. However, a new date was set for June 2018. On 23 June 2018, I was with my dive buddy, Karl Van Der Auwera, on the way to the port of Kiel in Germany. From Belgium, this was only a good 650km drive.

We embarked on a DFDS Seaways ferry that would deliver us the next day to the port city of Klaipėda in Lithuania. From there, it was only a 10-minute drive to our expedition ship, NZ 55. The owner of the ship is Linus Duoblys, and our dive team consisted of five divers from three different countries. My dive buddy and I would dive with closed-circuit rebreathers, but there were also team members who would make the dives with open-circuit systems.

The maximum depth we would reach on the wreck would be 82m. However, the water temperature at that depth was only 3°C. The good news was that the temperature at the stage depth was 15°C. The plan was to dive the next day on another wreck, which was 40m away, so that we were able to test our equipment.

The weather reports looked good for the next few days. This was important because the Carl Friedrich was 40 miles from the harbor.

Test dive

The wreck of the SS Edith Bosselmann could be reached after two hours’ sailing from the port of Klaipėda. Luckily, the weather was as predicted—calm—and there was hardly a wave to be seen on the sea.

This wreck upon which we would do our test dive was discovered two years ago and was located at a depth of 51m. The Edith Bosselmann was a cargo ship loaded with coal that sank on 9 December 1942 after a collision with a mine, which was laid by the Russian submarine L3.

When I started the dive on the Edith Bosselmann with my buddy, the visibility was not so good in the first 15m. But down on the wreck, visibility was about 12m. However, at 3°C, it was freezing cold at the bottom.

The wreck itself was positioned on its port side and partially covered by fishing gear. At the bottom, the lower part of the ship’s compass was clearly recognizable. After a short reconnoitre of the cargo holds, we swam towards the stern and noticed the propellers and rudder. The dive on the Edith Bosselmann was a good warm-up for our dive on the SMS Carl Friedrich the next day.

Underwater museum

After our dive on the Edith Bosselman, we prepared the rebreathers again, as we had to leave early the next day. The boat trip to the wreck took more than five hours for the one-way journey. Including the diving, we would certainly be on the move for 13 to 15 hours. However, we were lucky again with the weather, and the trip went smoothly.

The dive plan was such that Auwera and I would be the first team to launch. We did a final inspection of the equipment and jumped into the water to start our descent. At a depth of 15m, I started to feel the cold temperature of the water. But because it was our second dive, we were already a bit adapted to the cold, so it was not so bad.

The wreck was at a maximum depth of 82m, but when we landed on the bottom, we could not distinguish the wreck in the dark. We swam around to try and find it, because the downline could not be far from the wreck. After swimming around for 10 minutes, we decided to ascend. When we had risen about 15m, we suddenly saw the wreck and swam across the port side to the midship section. Here, we immediately saw the large guns that were turned outwards. It was a beautiful sight in the light of the camera lights, because the wreck was almost clear of marine growth.

Even pile worms cannot tolerate this cold water, and that was the reason why the wood, which was still on the deck, appeared like new. All the details, such as the ship's lights, were clearly visible on this wreck, which made it unique for a ship from the First World War.

We had a maximum bottom time of 25 minutes, and these were now used up, so we had to start our ascent. For the next two days, we went back to the wreck.

Our second dive was the best of all the dives because we managed to swim towards the bow of the wreck where we found a bronze plate with an eagle on it. On our way towards the bow, we filmed the bollards and various other parts; however, the view of the beautiful bronze eagle on the plate was the highlight of all the dives to the wreck. This alone made the trip to Lithuania more than worth it!

In search of the stern

During the last dive, we wanted to explore the stern and the bridge. The visibility was a lot less this time when we descended. The many fishing nets on the wreck made it a dangerous business, if one did not pay attention. We had landed back at the big guns, but a few meters farther on, we could see one of the smaller guns that was placed on the side of the ship.

We swam away from the sea bottom as there was a big silt cloud that reduced the visibility to almost zero. Here, we found various grenades, which were scattered over this part of the seabed. However, there was no sign of the propellers and some other parts of the ship. The part where the bridge was supposed to be was probably under a layer of mud, which was regrettable. In the future, an expedition will be undertaken to remove the fishing nets from the wrecks in Lithuania. ■

Having dived over 400 wrecks, Vic Verlinden is an avid, pioneering wreck diver, award-winning underwater photographer and dive guide from Belgium. His work has been published in dive magazines and technical diving publications in the United States, Russia, France, Germany, Belgium, United Kingdom and the Netherlands. He is the organizer of the tekDive-Europe technical dive show. See: tekdive-europe.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎