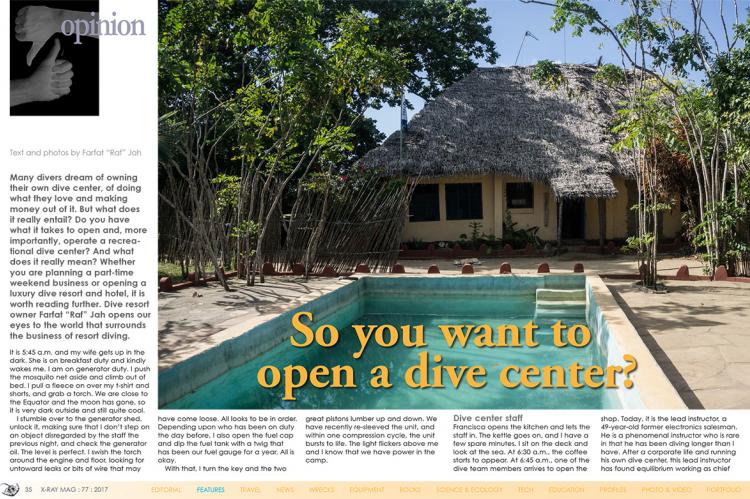

So you want open a dive center?

Many divers dream of owning their own dive center, of doing what they love and making money out of it. But what does it really entail? Do you have what it takes to open and, more importantly, operate a recreational dive center? And what does it really mean? Whether you are planning a part-time weekend business or opening a luxury dive resort and hotel, it is worth reading further. Dive resort owner Farfat "Raf" Jah opens our eyes to the world that surrounds the business of resort diving.

Tags & Taxonomy

It is 5:45 a.m. and my wife gets up in the dark. She is on breakfast duty and kindly wakes me. I am on generator duty. I push the mosquito net aside and climb out of bed. I pull a fleece on over my t-shirt and shorts, and grab a torch. We are close to the Equator and the moon has gone, so it is very dark outside and still quite cool.

I stumble over to the generator shed, unlock it, making sure that I don't step on an object disregarded by the staff the previous night, and check the generator oil. The level is perfect. I swish the torch around the engine and floor, looking for untoward leaks or bits of wire that may have come loose. All looks to be in order. Depending upon who has been on duty the day before, I also open the fuel cap and dip the fuel tank with a twig that has been our fuel gauge for a year. All is okay.

With that, I turn the key and the two great pistons lumber up and down. We have recently re-sleeved the unit, and within one compression cycle, the unit bursts to life. The light flickers above me and I know that we have power in the camp.

Dive center staff

Francisca opens the kitchen and lets the staff in. The kettle goes on, and I have a few spare minutes. I sit on the deck and look at the sea. At 6:30 a.m., the coffee starts to appear. At 6:45 a.m., one of the dive team members arrives to open the shop. Today, it is the lead instructor, a 49-year-old former electronics salesman. He is a phenomenal instructor who is rare in that he has been diving longer than I have. After a corporate life and running his own dive center, this lead instructor has found equilibrium working as chief instructor in Pemba. He lets the boat crew in, who take the fuel they need and filter it through a fuel-water separating funnel. Even with our 40hp workhorse type engines, the fuel quality is so bad that it must be filtered every day.

Captain Haji is a young man. He used to fish for a living, but for the past few years, he has been my skipper. He is as at home with twin 115hp engines as he is with 40hp. He is not fazed. He is a man of the sea. Like many of the villagers, he and his family have always made their living by the sea.

He and his team bring out cylinders, bags of dive gear and two 40hp outboard engines. They load all of this into the oxcart. The African oxcart with Land Rover wheels is the best way of getting our kit to the boat. The only thing missing is the ox. On busy days, the captain hires an ox from a farming friend of his. The team has to put the engines on and then remove them each night, as theft of the 40hp is rampant on the islands.

I take this time to look at the boat from the deck. I look to see if it sits right in the calm water and also for any abnormalities. Then as the crew load, I watch them pull start the engines. If the engines start the first time in the morning when cold, they are performing well. Multiple pulls could mean new spark plugs are required, or worse. Both engines start the first time. One is new and the other has just been rebuilt.

Everything about dive safety seems to be a combination of regular recorded servicing and observation. It is the observation of a minor glitch or client concern that encourages us to investigate. If we then find an issue, we can solve it, either by reassuring a client, changing to a spare, or fiberglassing a very small hole. It is all down to observation.

Checking everything

Some of the guests start to appear. They take coffee and sit on the deck. My quiet moment is over. Still in my fleece and shorts, I wander over to chat with the lead instructor and Haji. If Haji needs a hand with the heavy lifting, this is the time for me to weigh in. He rarely does.

I get the village gossip from Haji and ask the lead instructor if plans have changed. I may be the boss, and I may know more about the underwater world of the island than anyone else, but I have long learned that information is golden. I ask the instructor what he thinks—is all okay? It is not. Indeed, it is usually me that brings the news of more divers, who decided to go diving at the last minute the previous night, and the need to kit up more people and load more cylinders.

The instructor knows his stuff. Sometimes, I come across as an authoritarian type, but this is an illusion. I am never too proud not to change plans based upon someone else's better ideas. I like to think of myself as a rather gruff captain rather than an abject fascist—but as he says: "You do have your moods." To my shame, he is not wrong.

Planning

The divemaster appears and gets her orders or updates from either me or the instructor. We all must know exactly what we are doing. I am on the boat today, which in high season happens most days during the week. I try and keep it down, but a four- to five-day stint is not unusual. (I then try and spend three days out of the water on other tasks).

The tide is out today, so the lads are carrying kits a long way. It is 120m to the edge of the water, but they are getting on with it. I go up to the dive center to change into dive shorts and a company t-shirt. I come down with my camera (I rarely dive without one) and have breakfast last. This allows the guests to have the pick of the food, and I make do with what is left. This usually works fine.

Before heading off, I liaise with Francisca on any company administration-related jobs that need doing. Usually, this involves submitting a form such as VAT or statistics, or more often, chasing money.

Payment

In the past, we have had people make bookings but never showing up. So now, we require full prepayment in advance. Sixty days before arrival, the payment becomes non-refundable. But people do not always pay on time, and we are always chasing for the money. Sometimes, people arrive with only a deposit paid, and we must ask them to pay as soon as they walk in the door. Too many bad experiences make this an unpleasant necessity.

First dive of the day

At about 9:00 a.m., we are wading out to the boat. The tide is coming in, but we cannot get the boat in too close, so it is waist-deep water for all of us. I climb on the boat and sit at the back. A crew member hauls up the anchor, and Haji restarts the engine (which has been allowed to warm up).

On the way out, I either sit at the back and compose my thoughts or talk to students and divers. The boat is an old Tornado 8.2 RIB (which is, in fact, 8.6m long). The original tubes wore away a long time ago and I replaced them with fiberglass barrels. The boat is heavy, but extremely seaworthy and buoyant.

Twenty minutes later, we arrive at our dive site. We have already helped the first group of divers kit up, and they roll into the water, almost upon arrival. We find our dive sites by dead reckoning. Haji is pretty good at it, and I hold my own.

As soon as the first group are gone, the second group kit up and roll in. In this way, we can comfortably have two groups of five clients diving. Most of our diving is wall diving, which is simply spectacular, but you need to watch your depth, and we, the dive guides, are constantly looking behind us to make sure that no one has done anything stupid.

My briefing is clear: You are certified divers responsible for your own safety. And that means you, the diver, need to watch your own depth time and air. Problems occur when divers have neither watch nor computer. They will not buy a watch, and they will not rent one of my computers. I will not push the point, so all I can say is, "Stay above me." But realistically, there needs to be some form of industry-wide insistence that people dive with a timepiece.

The dive starts to come to an end when a diver runs low on air. At 70 bar (1000psi), I start to bring the group slowly up. Our dive may run for another 15 to 20 minutes after the start of the ascent, but it is a struggle to get people to tell us when they reach 70 bar, not 50 bar. There seems to be a perception among divers that it is okay to dive until 50 bar, at any depth, and then miraculously make it to the surface within 5 bar.

Beach interval

The instructor and the divemaster come up, and we are off to a small beach. At the beach, a crew member opens the cooler boxes and gets the fruit, tea and coffee out. He pours and chats away with his team. Some of the clients wander off to look at the crabs and fauna of the island. I check my phone for messages, telling Francisca where we are and listening to any info I need.

“Tell John and Jane their flight is confirmed” or “Morris’ luggage has still not been located” are normal messages. Then I turn to my people, for having coffee and tea and talking to our clients on a totally deserted beach with Haji is fun.

Divers are usually a fascinating bunch, and this is one of the joys of our job: meeting interesting, often like-minded people. We do occasionally get a bad apple, an abject racist or, more recently, an Islamophobe. These people can make our lives very difficult, as we must shield our other guests and staff from their rabid opinions. I sometimes wonder why people who hate Muslims travel to a country that is 98 percent Muslim. Thankfully, everyone is delightful today.

Haji gives me the nod and tells me that all tanks are changed and the boat is ready. He is usually bang on the money with timing. The lead instructor and I shepherd our people back onto the boat. My group of divers goes first as they were first out.

Second dive of the day

Our second dive is often as deep as the first and always multi-level, with much time spent in the shallows at the end. This time, after a short sojourn at 24m, we spend ages at 6 to 8m, in and out of the rocks and fans. I love the top of the dive site, Trigger Wall. You just need to watch out for the triggerfish during the mating season.

After the second dive, it is back on the boat for a final roll call and we steam back to the camp. I call it "steaming", as at six knots, we are not powering back and it is not quite sailing either. As we return, the boat crew packs away all the kits into the relevant bags, and the lead instructor and I ask if anyone would like to do a third dive. If the morning has been amazing, we usually get a load of repeat divers. Today, it is an average one or two.

Back at camp

We are almost back on time today—1:45 p.m. at the camp. The clients wash their kit and head off to shower. They will be eating by 2:00. We wash the regulators ourselves. It is me that does the servicing on the Aqua Lung Calypsos. I want to make sure that not a drop of water enters the first stage. I used to be the Aqua Lung distributor, but the French were painful to deal with, so we now buy whichever brand we get the best deals on. At the moment, it is Beuchat and Typhoon, but from MDE, a British company.

If Francisca is around and we are back reasonably early, she will wait and we can eat lunch together. But usually a client asks us to organize an afternoon tour or a flight off the island in a few days, so lunch can be a "working lunch.” I have noticed that anytime a client is near you, or can see you, you are fair game to be asked questions or simply chatted to.

Service

The diving industry is called a service industry. We exist solely to make our clients happy, and that means sorting out problems created by others, smoothening the path, finding lost luggage, re-booking flights, dealing with rogue safari operators (whom we do NOT use or recommend), or very often, just telling the Pemba story, or our story.

Francisca is an anthropologist and I studied politics and history. I have studied Africa, read up on it, and interviewed hundreds of people who have lived in Africa about their experiences. It is easy to lose an afternoon over coffee listening and explaining.

Food planning

Francisca wanders off to sort out dinner. Each meal must be carefully planned and this involves purchasing (as all our produce is fresh) and thrice daily issuance of food items. Our cooks literally need the food to be handed to them for each meal, otherwise you end up with a massive lunch and tiny dinner. For that is what the islanders do.

Food is absolutely vital to a dive center. Either you buy it in, or you make it. Either way, it has to be the best that you can make it. People underestimate the importance of good food. I have been to very few (but very unpleasantly memorable) dive resorts where the food is mediocre or bad. Whether we like it or not, we are accommodation with a dive center, not a dive shack with rooms. There is simply no way around this, and I have to keep reminding myself of this.

Day’s end

At this stage, most of the clients relax on the deck or beach, or sleep in their rooms. Francisca uses the time to catch up on the tasks that she missed out on in the morning. This is a much more relaxed time and all she has to do is to get dinner out.

I attend to some electronic paperwork, or do some equipment maintenance. We try to service every item, inspect and clean every tank and check every engine and item before the season starts. This usually guarantees that dive equipment stays in good shape throughout the season, but things do go wrong, clients do drag regulators through the sand, and no matter how many times you tell people, someone always throws a whole regulator into the dunk tank with a loose dust cover.

The day draws to a close, and as the sun sets, most guests wander down to the bar and deck to look at the horizon. It is a magnificent time of the day, and I either sit alone or with Francisca on the beach and watch it go down, or I lie down and rest for an hour. After that, I take a shower and then go down to see the guests.

Dinner

Dinner is a family affair with all of us sitting at one long table. When we have loads of pre-booked divers and diving is easy, we know exactly what we are doing. The hotel and dive team sit by the pool and briefly discuss the next day’s plan. But when we have a series of walk-in guests, or accommodation for only pre-booked guests, then I do the rounds during dinner, sometimes with a clipboard, asking who would like to do what. After we have an idea, we sit down and work out how we can accommodate everyone’s wishes, i.e. two try dives, an open water course, and some recreational diving. Sometimes, when we are really busy, we help serve dinner, and then eat later.

As soon as dinner is done, Francisca feeds the dogs, and we stroll back up to the house and have 30 minutes free to read or listen to the radio before I fall asleep. It has been a long day, but a fairly typical one, and a fruitful one. ■

Farfat "Raf" Jah is an underwater photographer based in Pemba, Tanzania. He leads specialist bush walking safaris and operates a dive resort on the island of Pemba. See: Swahilidivers.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎