US & EU keep makos unprotected

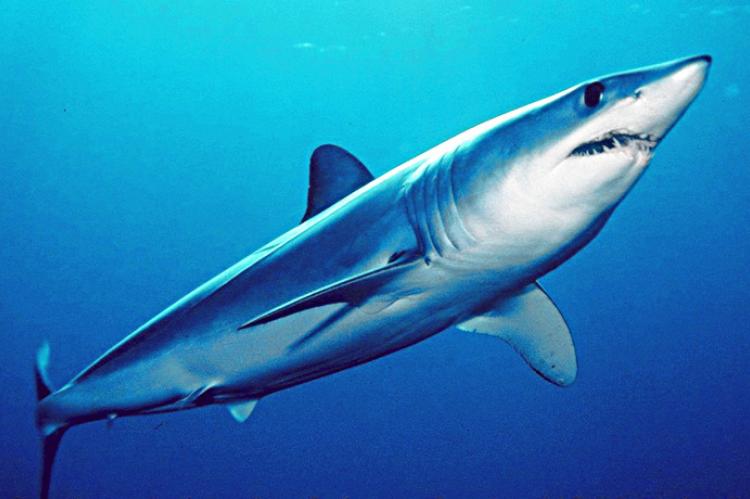

The shortfin mako shark fishery of the north Atlantic is one of those that fisheries scientists have claimed to be potentially sustainable. It has been used to promote the idea that all shark fisheries can become sustainable, with the United States in the lead. But in the meantime, the species has become globally endangered, and now, when other countries are urgently fighting for protection for the shortfin mako shark, the United States and the European Union have blocked it at the annual meeting of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT).

Ten countries, led by Senegal and Canada, proposed banning the retention of the seriously overfished mako shark, which is what ICCAT scientists advised. Yet the European Union and the United States refused to give up on exceptions for hundreds of tons of the endangered species to be landed.

The European Union ranks first and the United States ranks third in shortfin mako landings, suggesting that the important point when action is needed remains the continuing profits of fisheries, rather than conservation concerns. The catastrophic loss of sharks and the threats to the ecological health of the oceans are not of prime concern in spite of all of the rhetoric put forth in discussions about such matters, which highlights the difficulties inherent in protecting valuable animals. Shark fins are now so valuable that the profit from the fins has become prime, even in the case of the commercial shark fisheries that have traditionally targeted sharks for meat.

Like other cold-water sharks, shortfin makos are slow-growing and so are especially vulnerable to overfishing. They are killed for sport, as well as for their meat and fins, and though they are fished by many nations worldwide, they are not subject to international fishing quotas. It is thought by ICCAT scientists that the population of shortfin makos in the North Atlantic could take 50 years to recover, even if fishing is stopped completely.

At the ICCAT meeting, the science-based North Atlantic ban on fishing shortfin mako sharks was proposed by Senegal, Canada, The Gambia, Gabon, Panama, Liberia, Guatemala, Angola, El Salvador and Egypt, and was supported by Norway, Guinea Bissau, Uruguay, Japan, China and Taiwan. No countries spoke in favor of the competing EU or US proposals, although Curaçao added their name to the US proposal.

This species was assessed on the IUCN Red List in 2000 as being "Lower Risk/Near Threatened," and in 2009, it was reclassified as "Vulnerable." But in 2017, the shortfin mako fishery in the North Atlantic Ocean was reported in a scientific fisheries study to be a "bright spot" of shark fishing sustainability. Yet that same year, the stock assessment on the NOAA Fisheries website showed that this shark was overfished and that overfishing was occurring. The IUCN subsequently re-classified the shortfin mako from "Vulnerable" to "Endangered" worldwide, with a decreasing population trend. So in 2019, US fisheries began working on a management plan and urged fishermen to reduce catches voluntarily in the meantime.

Thus, fisheries management in the United States, which claims to be the best in the world, allowed this species to go from "Lower Risk" to "Vulnerable" to "Endangered" in less than 20 years, with no conservation action. Only after the shark became endangered, in 2019, did they begin working on “a plan.” And now they have blocked international protection for the species.

It is clear that the "sustainable shark fishery" management approach is not working to maintain shark populations. As reflected in every global study of the status of sharks in recent years, fisheries management has completely failed this line of animals, which is the worst off of all vertebrates, in spite of their incalculable ecological importance.

ICCAT scientists are concerned that South Atlantic shortfin mako sharks may be in a similar situation, and Senegal included a science-based catch limit for this population in their proposal. ICCAT parties plan to hold a special inter-sessional meeting next year to continue discussions on the shortfin mako shark.

A record number of parties (33 of the 47 present) cosponsored a proposal to strengthen the ICCAT’s ban on finning (slicing off a shark’s fins and discarding the body at sea) by replacing a problematic fin-to-carcass ratio with a more enforceable requirement for sharks to be landed with fins attached. As they have repeatedly in the past, Japan and China blocked the measure.

The ICCAT did adopt catch limits for blue sharks for the first time, and as a result, science-based limits on blue sharks will be put in place for the North and South Atlantic. In addition, the ICCAT adopted revised text which is hoped will modernize the convention and strengthen future measures for shark conservation once it is ratified. ■