Migrating humpback whales have poor health on return journey

Researchers from the University of New South Wales have discovered that migrating humpback whales are in poorer health during their return journey back to Antarctica, through analysis of their whale blow.

UNSW researcher Dr Catharina Vendl holding the telescopic pole she used to collect samples of whales' blow in Hervey Bay, Queensland, in 2017.

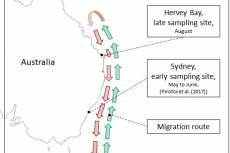

Every summer, East Australian humpback whales migrate from the feeding grounds in Antarctica to their breeding grounds in the Great Barrier Reef. They remain there for about several months, before making their way around the southern Australian coast back to Antarctica for the winter.

By analysing samples of the whales’ blow, researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) discovered that the whales are likely to be in poorer health during their return journey. Not that this was surprising, considering that the physical strain of migration, as well as the fact that the whales fast for most of the journey.

Samples of mucus taken during the whales' 2017 migration revealed that there was "significantly less" microbial diversity and richness in their mucus taken on their return journey, compared to the samples taken at the start of the migration by Macquarie University scientists in Sydney. This showed that the whales were likely in poorer health on their return journey.

Findings of the research was published on July 28th in the Scientific Reports journal.

Lead researcher Dr Catharina Vendl said, "We concluded the physical strains of the migration, likely in addition to the exposure to marine pollutants, compromise the whales' immune systems and consequently cause a shift in the whales' airway microbiota."

This study also provides the first evidence that the whales' airway microbiota (based on analysis of the mucus that emerges from the whales' blowholes) was a potential indicator of a whale's overall health. "Our findings are the first to provide good evidence of a connection between the whales' airway bacterial communities, their physiology and immune function—something that has been established in humans," she added.

Samples taken non-invasively

In addition, the samples were taken non-invasively, using either waterproof drones carrying petri dishes, or by using a 4.6m pole with petri dishes at the end of it. Dr Vendl hoped that her research would lead to further study in non-invasive techniques to monitor whale health in populations worldwide.

"Analysing whale blow to assess and monitor whale health opens up more possibilities for the use of non-invasive techniques, such as photogrammetry—where you fly a drone to film and measure whales to determine how much blubber they have and things like that."

"Other methods were outside the scope of my PhD, but it's important for researchers to experiment with and refine new techniques to assess their effectiveness in helping whale conservation," she added.